Antisemitism is actually a sign of Jewish strength.

When Jews look into the eyes of their haters, they may feel weak, but antisemites are really acknowledging Jewish greatness.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is an edited excerpt from the new book, “Who's Afraid of the Big, Bad Jew: Learning to Love the Lessons of Jew-Hatred” — written by Raphael Shore, an acclaimed filmmaker and author.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Abraham’s discovery of God — infinite yet personal — was humanity’s greatest discovery.

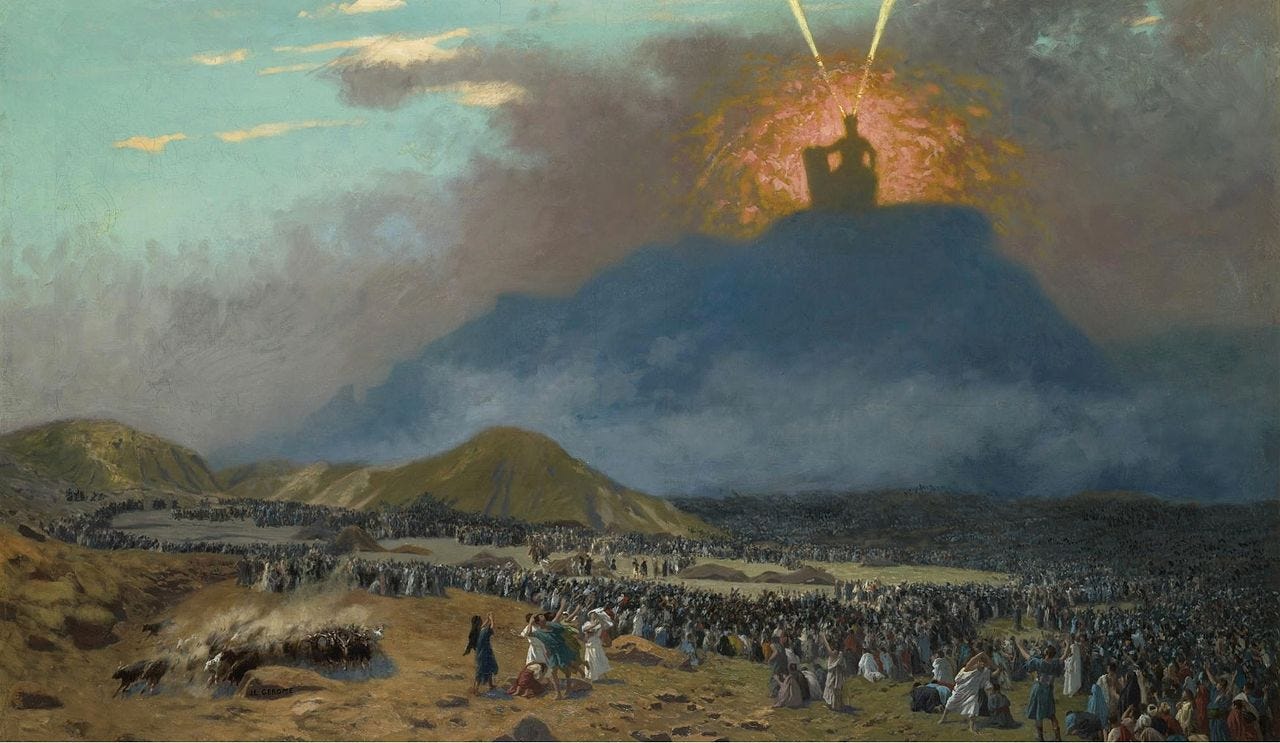

And Abraham went further: He questioned, formulated, and articulated a complete system of philosophy and ethics that was world-shattering. These principles became the foundations of Judaism; Abraham had accessed the Divine life principles that seven generations later were concretized at the great revelation of the Torah at Mount Sinai.

Judaism believes that all human history (and, thus, every individual human life) is the story of this battle with the human condition. And that salvation, both personal and global, is dependent upon the victory of the human concept. Best-selling author Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Jacobson says it well:

“The struggles to integrate the Divine and the human, matter and spirit, body and soul, the inner and the outer, are as old as history itself. The tension between these opposing but complementary forces lie at the root of all conflict: inner (personal) and outer (social and political).”

The Nazi Response: A War of Worldviews

Hitler said, “No nation will be able to withdraw or even remain at a distance from this historical conflict.”

The Nazis believed that spirituality dehumanizes man, while Judaism holds that man humanizes the universe. The Torah illustrates this worldview eloquently through the story of Rebecca.

While still in her womb, Rebecca’s twins fought desperately, causing her such anguish and pain that she sought out a prophet to explain the unusual nature of her pregnancy. The prophet revealed that she was carrying two diametrically opposed leaders. The 19th-century Jewish philosopher Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch explained the prophetic response:

“Rebecca was informed that she carried two nations in her womb who would represent two different forms of social government. The one state would build up its greatness on spirit and morals, on the humane in humans, the other would seek its greatness in cunning and strength. Spirit versus strength, morality versus violence oppose each other, and indeed, from birth onwards will they be in opposition to each other ...”

“The whole of history is nothing else than a struggle as to whether spirit or sword, or, as our sages put it, whether Caesarea or Jerusalem is to have the upper hand.”

Judaism and Nazism share a common worldview: There is another world war, one more significant than the battles fought with guns and tanks — an epic ideological struggle.

The Nazis fought on the side of brute force and the Jews on the side of love. One side wielded the might of a vast army and empire; the other commanded an empire of the spirit. The Nazis sought to destroy the moral power of the Jews with raw force, through degradation and deprivation, killing millions, and yet they could not achieve their goal.

Hermann Rauschning, a former Nazi, tried to alert the world to these ideas. As the President of the Senate of the Free City of Danzig from 1932 to 1934, he had several conversations with Hitler, which led him to subsequently reject the Nazi movement and flee to the United States. He wrote several books before and during the war in a desperate attempt to show the free world that Nazism was a serious threat, warning:

“The new element (Nazism) is, at the same time, of immemorial age. It is the craving, suddenly grown to immense urgency, to throw off domestication and all civilized restrictions ... Be not deceived: this urge to return to the primitive is felt not only by the Germans. Among the masses everywhere there is the same strong desire to throw off the burdens and obligations of a higher humanity.”

This is the same human struggle that author Fyodor Dostoevsky so powerfully described through the character of Ivan Karamazov in “The Brothers Karamazov.”

Set in Spain during the bloody days of the Christian Inquisition, Jesus appears and is arrested by the Grand Inquisitor, who proceeds to lecture him. The Inquisitor argues that Jesus’ mistake and sin was expecting too much of humanity; by placing on people the moral burden of freedom and a moral code, he demanded too much. For this sin, the Inquisitor plans to burn Jesus at the stake for imposing the Judeo-Christian worldview:

“You want to go into the world ... with some promise of freedom which they (humanity) in their simplicity and innate lawlessness cannot even comprehend, which they dread and fear — for nothing has ever been more insufferable for man and for human society than freedom!”

Ivan had identified man’s discomfort with the burden of personal responsibility:

“Instead of taking over men’s freedom, you increased it still more for them! Did you forget that peace (of mind) and even death are dearer to man than free choice and the knowledge of good and evil? There is nothing more seductive for man than the freedom of his conscience, but there is nothing more tormenting either.”

Jesus’ mistake was that he had “...overestimated mankind ... I swear, man is created weaker and baser than you thought him! ... Respecting him so much, you behaved as if you had ceased to be compassionate, because you demanded too much of him ... Respecting him less, you would have demanded less of him, and that would be closer to love, for his burden would be lighter. He is weak...”

That struggle continues today, on the global scale of world power and within each of us. This conflict is the fault line of the human condition; on this point, the Torah, Hitler, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche agree.

The Nazi Revolution was a modern rebellion against the call to civilization — the call to Sinai. During and after World War II, the Arab and radical Islamic worlds, including Hamas and Iran, picked up the baton.

Three thousand years ago, the Psalmist King David prophesied about how the world would chafe at the ethical responsibilities of Jewish values:

“Why do the people gather, and the nations talk in vain? The kings of the earth take their stand and the lords conspire secretly, against G‐d and his anointed (the Jews), saying: ‘Let us cut their cords [of the moral burden] and cast off their ropes.’”

This is why the Talmud states, in a play on words, that at Mount Sinai, sinah (the Hebrew word for hatred) came into the world. While Jew-hate certainly predated Sinai, it now had a powerful new motivator aimed at the Jews. It was there, at the dawn of a new era in human history, when the Ten Commandments and the Torah were given, that antisemitism took on its profound significance.

Hitler said it directly, as quoted by Rauschning: “The Ten Commandments have lost their validity.”

Beginning with Abraham, a spiritual revolution emerged that introduced a new outlook into the world. This revolution was so successful that, 3,700 years later, one of the most powerful nations in the world, Germany, launched a campaign of genocide to eradicate it.

Hitler observed, with fear and disgust, that most of the modern world had embraced the ideas brought to the world by Abraham and the revelation at Sinai. These Jewish teachings promote values that are now widely accepted: classic Western liberalism, rejecting the primitive ideals of “might makes right,” and instead striving for equal and human rights and the dignity and sanctity of life.

They advocate for caring for the oppressed and downtrodden, promoting universal education, creating social welfare programs to help the sick and needy, encouraging tolerance, working to end racism, and fostering peace and the end to violence and war. These ideals, which are fundamental to Judaism, were not widely accepted when they were first introduced.

It is no coincidence that one of the freest countries in human history has a verse from the Hebrew Bible inscribed on its Liberty Bell: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

It is also no coincidence that the global institution tasked with working for world peace, the United Nations, takes its vision from the Jewish prophet Isaiah: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.”

But over the thousands of years that it took humanity to get to where it became “self-evident” that “all men are created equal,” there has been resistance every step of the way.

There is a body-soul push and pull through history; as the lofty and holy ideas are slowly and painfully integrated into civilization, they are simultaneously resisted. The pushback is called antisemitism.

That the Jewish People are sometimes worn out and discouraged is understandable.

The scope of Jewish pain is so deep and beyond description that the continued commitment of the Jewish People is remarkable. They’ve endured millennia of relentless hatred, bullying, oppression, crusades, pogroms, and the Holocaust, producing multigenerational trauma that is profound and often beyond description.

The toll on the Jewish psyche is immense, as Jew-haters have been sought to solve the “Jewish problem” in every generation, leading to deep and lasting scars.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks poignantly wrote of the consequences of antisemitism and the Holocaust: “Collective traumas of this magnitude take several generations to play themselves out, and we still live with their aftershocks. Like Jacob after his wrestling match with the angel, we limp.”

In clinical terms, it is accurate to say that the Jewish People suffer from multigenerational PTSD.

So, how do we respond to these very profound experiences and pressures? How do we retain our sense of self and define our identity?

Approach #1: Defense

When Jews encounter antisemitism, they can feel inferior, buying into the charges against them that they are, in some way, the problem.

In response to being disliked, Jews try to adapt to the accusations against them and hope for acceptance. They appeal to their detractors to stop hating them, saying, “We are not what you accuse us of; we are just like you, and everyone should be nice.”

In the past couple of centuries, the Jewish People have been playing defense.

Many Jews cope with antisemitism by trying to “fit in.” They undergo social and intellectual “makeovers” to change themselves into the opposite of what the antisemites claim to hate about Jews. Starting in the early 1800s, the objection to the Jews was that they were too different. Convinced that by becoming like everyone else they would neutralize the detractors, Jews made an effort to become less Jewish.

As the saying goes, “How did that work out for you?”

When I was a college student in Toronto, Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel visited. I heard him compare the Jewish People to a messenger that got hit on the head. When the messenger woke up, he couldn’t remember four things:

Who sent him

To whom he was sent

What the content of the message was

That he was, in fact, a messenger

This national memory loss, this diminishment of Jewish moral self-confidence, is, in fact, the true victory of the antisemite. It is why philosopher Emil Fackenheim famously declared the concept of the “614th commandment” as the moral imperative for Jews not to give Hitler a “posthumous victory” by assimilating.

Perhaps it’s time we write a new ending to our story.

The process of recovery and personal growth can only begin by acknowledging that, in many ways, we have lost our way and we need help. As Leonard Cohen poetically warned Montreal’s Jewish leadership in a 1963 address:

“Now, before we begin we must face that despair that none of us dares articulate: that we no longer feel we are holy. There will be no psalms, there will be no light, there will be no illumination until we can confess the position into which we have decayed.”

But this recognition of our current state can be the first step toward renewal and strength. Just as our ancestors have done throughout history, we can rise and reclaim our connection — with ourselves and with God — so we can move forward with resilience and embrace our sacred mission.

Approach #2: Resilience and Grit Judaism

In response to the Nazi yellow star, German–Jewish World War I veteran Robert Weltsch published an inspiring message to his brethren, entitled “Wear It With Pride.” He wrote:

“April 1, 1933, could be the day of Jewish awakening and rebirth if the Jews desire it, if they show maturity and greatness within them, and if they are not as misrepresented by their opponents. Under attack, the Jews must acknowledge themselves. It is not true that the Jews betrayed Germany. If they betrayed anyone, it was themselves, the Jews. Because the Jew did not display his Judaism with pride, because he tried to avoid the Jewish issue, he must bear part of the blame for the degradation of the Jews.”

Since October 7th, a choice has been forced upon us by Hamas and the global community, just as Germany challenged the Jews 100 years ago. There is again a unique opportunity to rekindle the Jewish spirit, to rediscover our self-worth that transcends the scars of the past and embraces a proud heritage.

The choice is not easy, but it is simple: to embrace ourselves, our history, peoplehood, and mission, or to deny.

This gritty approach is expressed humorously in the old Jewish joke about two elderly Jews riding a train in 1930s Germany. One of them is reading a Jewish paper while the other is eagerly turning the pages of Der Sturmer, Streicher’s violently antisemitic Nazi rag:

“How can you read that filth?” the first Jew asks. “Simple,” his friend replies. “In your paper, Jews are being beaten, robbed, and deported. But in the Nazi paper, it’s all good news. I just found out that the Jews control the entire world!”

The deepest victory over Hitler and antisemitism comes when the Jews stop defining themselves by this hatred and instead embrace their identity. Our real education begins not when we escape antisemitism, but when we confront it.

Antisemitism, seen from this perspective, actually acknowledges Jewish impact and exposes the failings of the antisemites themselves. Embracing our Jewish identity starts with understanding why we have been targets of hate, but it flourishes only with a deep understanding of who we truly are.

Learning this secret unlocks our potential — not just as a people, but as individuals. The real power of the Jewish people is not about controlling governments or manipulating economies, as our detractors falsely claim. It is about each of us striving to become the best version of ourselves. As the Torah says, we are a “stiff-necked people.” This can mean we are slow to learn our lessons, but it also signifies a positive trait: conviction, resilience, and clarity of purpose.

We can either be paralyzed by resurging Jew-hatred, or we can understand that it’s provoked by the good we represent. With this understanding, we can stand tall with pride, moral clarity, and conviction.

To be Jewish is to be a messenger, carrying mystical knowledge across generations. Even when we forget the message, we are hunted for that knowledge. Leaving behind the message doesn’t mean antisemitism leaves us. Jewish history has two sides:

On one side, Jewish greatness shines through even in the darkest of times.

On the other, antisemitic hatred casts a shadow.

When Jews look into the eyes of their haters, they may feel weak, but antisemites are really acknowledging Jewish greatness.

Jews with grit and resilience understand antisemitism is not caused by them; it is the result of the antisemite’s weakness. They see antisemitism as a confirmation of Jewish strength, not a condemnation. For these Jews, antisemitism is a measure of Jewish success. It is a reminder of our incredible journey through time and history, across lands, empires, and ideas.

Thanks for a beautiful article, Rafael. I've always seen being Jewish as a special gift, and an incredible way of seeing the world.

I feel it's important to remain a light to the nations, especially now. It's important to remember our moral compass.

Jealousy and envy are essential to hate. That Jews are hated means that those who hate us are jealous and envious. They hate that Jews have risen above jealousy and hate. They hate that Jews are wired to be the best they can, while the haters are lazy and steal so they don't have to put forth effort. They hate that Jews have close family and community. They hate that Jews are successful. They hate that Jews have the strength and resilience to overcome the hate through the ages. Do not cower from the haters because they have no strength. The haters have just weakness and evil.