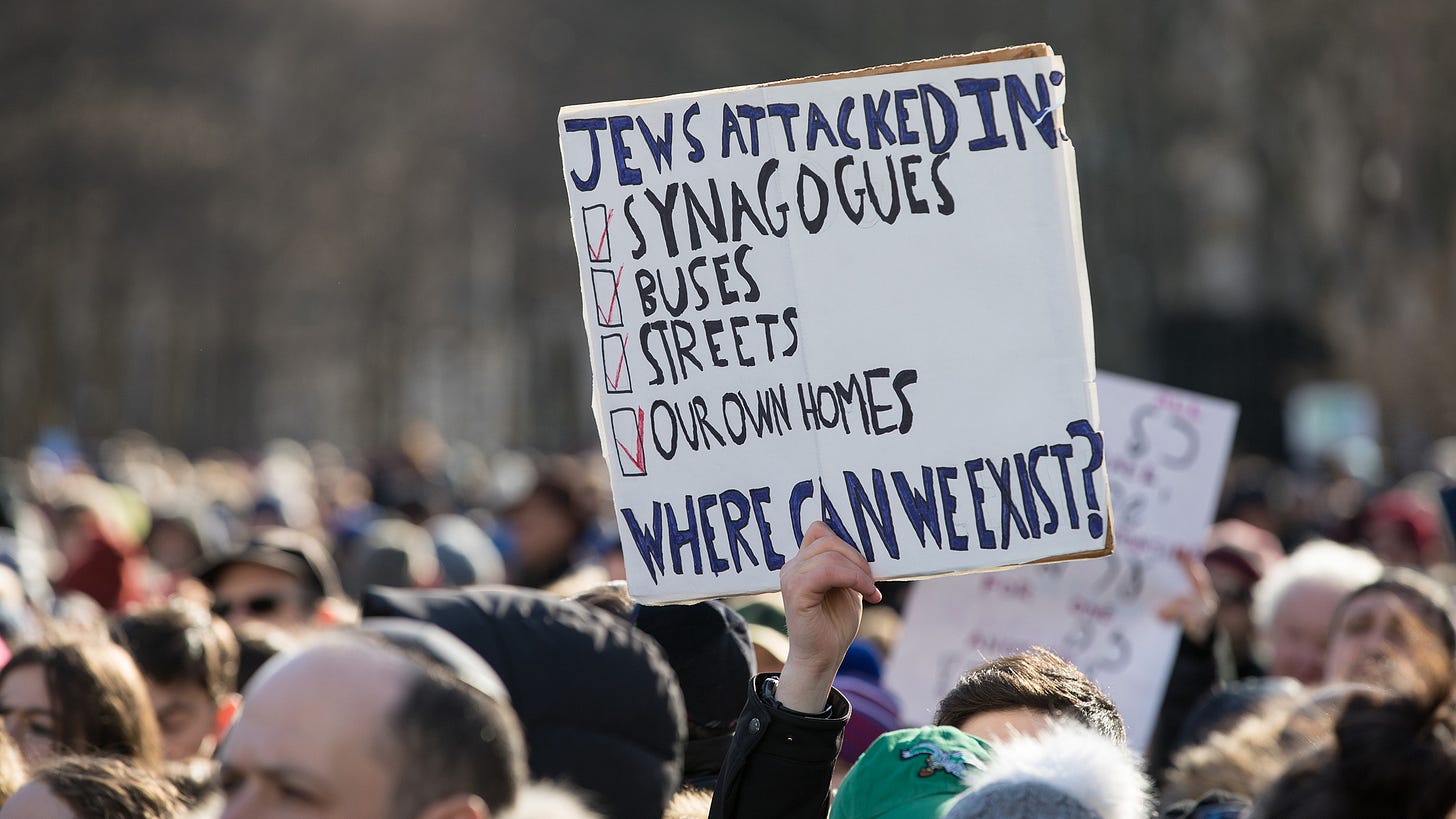

It's time to admit: Jews have made little progress in overcoming antisemitism.

Diaspora Jewry’s response to antisemitism has predominantly been the Holocaust — as if showing Jew haters what other Jew haters succeeded in doing will mitigate antisemitism.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay written by Saul Goldman. You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

Victimhood is about the way in which victims behave.

It is a response to aggression that reflects what Austrian psychologist Bruno Bettleheim described as “identification with the aggressor.”

There is the obvious element of prejudice that eventually boils up into a frenzy of violence. Ordinary prejudice expresses itself socially, such as country clubs and fraternities that exclude Jews.

In many ways it was a passive form of prejudice. People who do not like Jews just stay clear of them. They keep them out of their clubs and hotels. Most people are prejudiced about things. Once American cities had Jewish, Irish, and Italian neighborhoods. Of course there were White Anglo-Saxon Protestant neighborhoods.

And people felt this was not a bad idea. Social psychologists believed that contact between different groups only led to increased prejudice and conflict. What this implied was that if different groups of people kept their distance from each other or remained in their “own space,” there would be less friction and prejudice. This, of course, was antithetical to the American vision of the “melting pot.”

In the early 1950s, American psychologist Gordon Allport, probably idealizing the “melting pot” theory, published a monumental study about prejudice — in which he challenged the conventional view. Allport argued to the contrary: The more intensive the contact, the less prejudice. The more people melted down into a more or less homogenous entity, the less prejudice.

Apparently, Allport was wrong about this. In the United States, where an uptick of Jew hatred has astonished almost everyone, intergroup contacts between Jews and Blacks and Jews and academics have been the most intensive in history. Yet, everywhere from Harvard to Stanford, Jew hatred is abounding — and its being crystalized in the form of anti-Israel and anti-Zionism and “Palestinianism.”

But, Allport was not wrong about everything. He also attempted to measure prejudice and understood its connection to violence. He argued that prejudice begins in what he termed “anti-locution” — the ways in which people speak about Jews behind their backs.

As prejudice intensifies, they begin to verbally attack Jews. Ultimately the words become deeds and it ends up in violence. In other words, Allport argued that even simple prejudice, if left unchecked, can develop into an extreme form.

So, what does this mean for us Jews?

First, it disproves the old adage that “sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me.” Second, it sheds some light upon the Jewish dilemma of victimhood.

The fact is that Jew hatred is probably the world’s oldest prejudice. Yet, we have made little progress in understanding or in overcoming the condition of victimhood. We have interesting theories about why people hate us. However, there is little evidence that Jews have made progress in changing the kind of character that makes Jews the easiest object of frustration and hatred.

A relatively new discipline developed by Romanian lawyer Benjamin Mendelsohn, whose family was murdered by the Germans, might help us understand why Jew hatred is the world’s oldest prejudice. As far as I know, it was first addressed by Roman-Jewish historian and military leader, Flavius Josephus, in his pre-Anti-Defamation League tract, “Against Apion.”

What we take away from his essay is that antisemitism is not a prejudice that arises out of ignorance or dumb people. Apion was an Alexandrian philosopher. He utilized both rhetoric and his writings to develop this kind of prejudice for the common people of Alexandria.

One might describe his work as an ancient Hellenistic prototype for Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” or Karl Lueger’s “Reichspost” (a vicious Catholic newspaper that spewed antisemitism). Both Apion and Lueger accused the Jews of disloyalty; a canard that was repeatedly used against Jews. Even now, many American politicians — for example — believe that Jewish Americans are more loyal to Israel than to America.

German psychologist Hans von Hentig was also a “victimologist” — one who studies the behavior of the victim. He concluded that the young, elderly, and women are more susceptible to victimization because of their physical vulnerabilities. This, of course, is very logical; pick a target that cannot fight back.

The late Rabbi Kahane organized the Jewish Defense League probably with von Hentig’s conclusions in mind. Although the JDL was ostracized by Jewish leaders, it did raise the possibility of a more vigorous response; a possible way of rejecting victimhood.

It is interesting that Diaspora Jewry’s response to antisemitism has predominantly been the Holocaust — as if showing Jew haters what other Jew haters succeeded in doing will mitigate antisemitism in Europe or North America or South Africa or Australia.

Holocaust scholars have taught us a great deal about the Holocaust. However, they have not asked one of the most difficult and painful questions: What were European Jews thinking? Of course, the Germans rounded up Jews and murdered them. But, they were assisted by almost everyone else in the world.

Jew hatred did not spontaneously appear in Germany in the middle of the last century. Certainly, everyone knew about Jew hatred. Historians wrote about it and our holidays like Purim memorialized it. Yet, neither the Jewish communities in Europe nor the Jewish community in America ever organized in anticipation of a hostile event.

There is no question that the German army could easily round up all the Jews and murder them. But, no one knows what would have changed if the Jews had been organized in their determination to not be victims.

In the light of European Jewry’s mass capitulation to the German war machine, we must seriously question our continued passivity in the face of the newest antisemitic pogrom: Who really believes that a letter to the editor is an adequate response to the BDS assault upon Israel?

Years ago, I addressed my congregation on the anniversary of Kristallnacht. There were many Holocaust survivors at that time. I began my sermon by repeating the slogan: “Never Again.” Everyone nodded their heads and uttered some sort of agreement.

Then I asked, “How many of you own a pistol or rifle and have taught your children to shoot straight?” They answered me: “But rabbi, guns are illegal.” (They were not.)

My congregants offered me an insight into the psychology of the victim. Apparently, we have not even developed a consciousness and a resolve to never be victims again.

The mantra “Never Again” seems to be no more than a ritual; an obsessive refrain that has little effect upon our consciousness. We seem to continue evoking the same defense mechanisms that distort reality; denial and projection are two that come to mind.

For example, we have a tendency to let others defend us. We expect that the law will defend the Jews. Yet, it has been obvious for a long time that city police or campus police have been indifferent or even hostile. Recall the London police officer who told a Jewish woman that she “must see the swastika in context.”

Perhaps most insidiously is that we have created a theology of victimhood in which we idealize the victims. We call them :martyrs.” A martyr is someone who consciously chooses death rather than capitulate to an idea such as conversion to Christianity.

Judaism commands neither victimhood nor martyrdom. The actual commandment is “choose life” — even if we must fight for it.

And that ought to be one of the reminders for this year’s Passover.

I commend you for writing this. Even today, we are not fighting back. Why is Krav Maga not offered throughout Jewish communities. Why are we allowing ourselves to be locked into buildings with a murderous mob outside. Stop cowering and walkout with your head held high. It appears that we are never in the right, so what do we have to lose. We must all act as warriors. Hag Sameach

I'm not Jewish, but I try defending my Jewish brethran as best I can. I wish I could do more. My faith compels it. [#ChristianZionism] [as well as my love for all things Jewish] I use social media to dispel the antiSemitic lies as best I can [about Israel & Jews], I donate to Jewish causes [like this one] & I pray for you all. [4 your safety] Is there anything else I can do? I find antiSemitism to be Satanic, straight from the pit of hell. IMO, it's a supernatural hatred that defies explanation.