The Very Necessary Rise of Jewish Late Bloomers

Or, why fulfilling one's Jewishness later in life is advantageous to the individual and beneficial to the Jewish People.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free and zero-advertising for all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

For 25 years, Kathleen Hayes, a Jewish Brit, was “Defender of the Palestinians.”

She believed this was the path to a more just world. It seized her soul, she’d tell you.

“My group was notorious, even on the far left, for its extremism and sectarianism, but I’d have felt perfectly at home in the ‘Solidarity with Palestine’ antisemitic carnivals now taking place around the world,” said Hayes. “The occasional placard, chant, or demonstrator might trouble me — an overt blood libel here, a Rothschild conspiracy theory there — but I considered these aberrations: abhorrent certainly, necessary to fight, but easily separable from a righteous cause.”1

“Now I want to puke,” said Hayes, in reaction to October 7th, adding that the Palestinian terror attacks intensified her sense of being Jewish.

“I’d been tentative til then — there’s too much I didn’t grow up with, don’t know,” she said. “The horrors gave me clarity: My people are under attack. I will be with them.”2

Hayes is a classic case of the “Jewish late bloomer” — someone who fulfills their Judaism and Jewishness later than expected.

Though some people have profiles that neatly fit Jewish templates, many others possess profiles that are not well-matched for certain expectations. And no matter how many Jewish early bloomers there are, there are a lot of Jews who are not. All of this hinders the Jewish People’s thriving continuity and devalues Judaism itself, because it disregards far more people than it rewards.

The truth is, many factors can slow our Jewish blooming early in life, such as lack of effective education, nonstandard learning styles, socioeconomic status, lack of ongoing Jewish engagement opportunities, lack of accommodations for “atypical” Jews, being fed the “wrong” definition of Judaism and Jewishness, geographical restrictions, and even childhood traumas.

When you are born in Jewish history is also a factor. For example, among Jews who were born immediately after the Holocaust, their Judaism and Jewishness is likely to be a fierce reflection of these unfathomable events. But when these Jews imparted their Judaism and Jewishness to, say, their children, sometimes there was a proverbial leak in the ceiling — because their children are a generation removed from the Holocaust.

And for Jews who remember a time when you could wake up on any given day to news that Israel has been wiped out, overthrown, or conquered, the Jewish state was (and still is) an understandably epic part of their Jewish identity. But for Jews who only know Israel is mighty and strong, the Jewish state might serve as less of an impetus for their Judaism and Jewishness.

If you “fall behind” in the Jewish world, it can be difficult to catch up. Adult education, while available, is not efficient or comprehensive, and many Jewish institutions and organizations largely “serve” quintessential Jews, making those who fail to fit such a narrow mold feel like outsiders.

This is an enormous problem in the Jewish world today, because it affects so many of us Jews and would-be Jews, which has mounting repercussions on Jewish continuity, Jewish unity, antisemitism, and so forth.

As a result, interfaith marriage rates continue to rise amongst non-Orthodox Jews, and institutional affiliations and support for Israel continue to decline. And as a result of these results, we’re told or made to feel like we’re “bad Jews.” Or we’re shamed, implicitly or explicitly, for not falling in line with the rest.

Then, as we age, circumstances and responsibilities take away from the time and energy required to submerge ourselves in Judaism and affect our Jewish trajectory, leaving us to experience a culturally induced sense of marginalization.

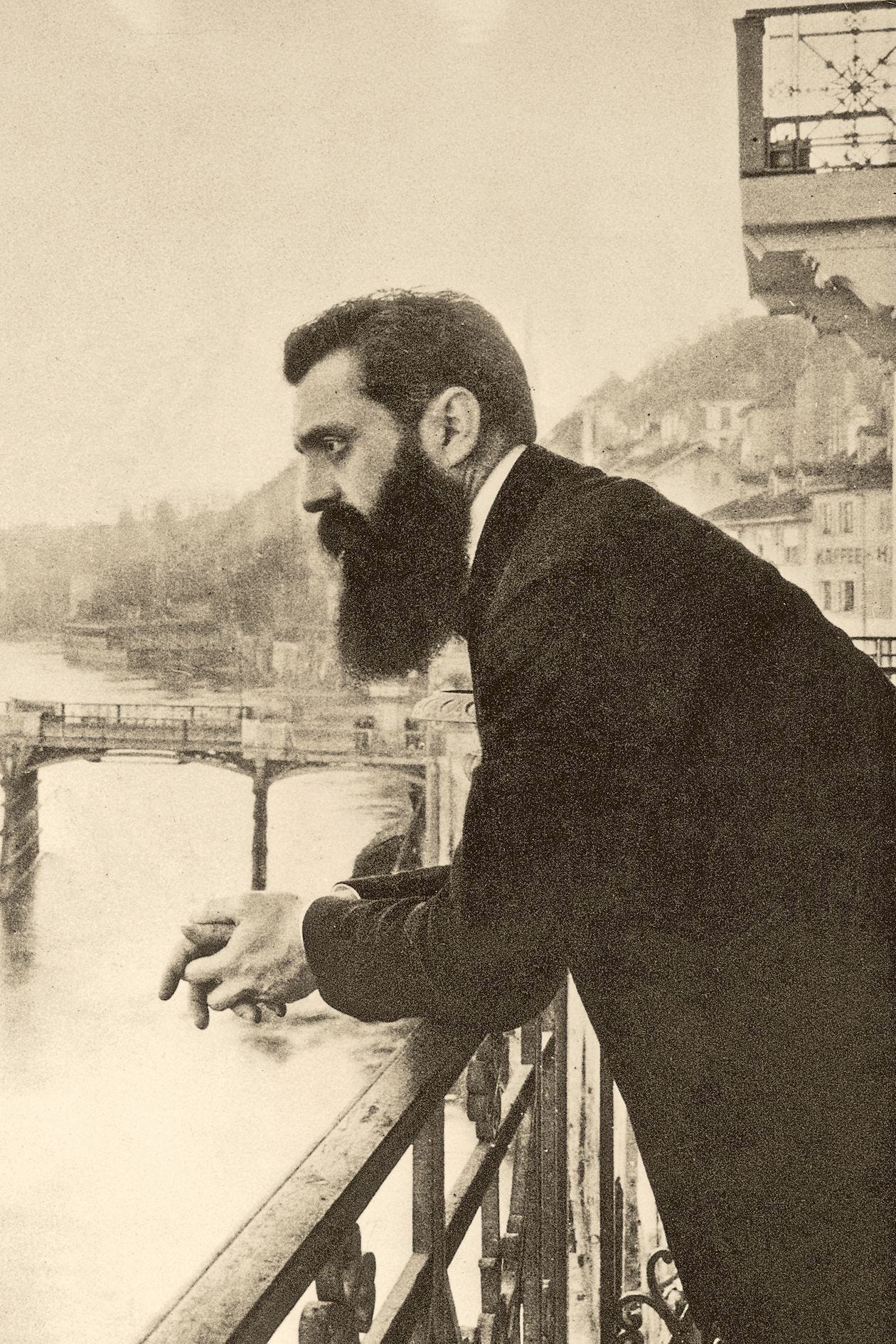

The critical thing to remember is, we cannot give up on ourselves and on others. For example, Theodor Herzl as a young man was an ardent Germanophile who saw the Germans as the best cultured people in Central Europe, and believed Hungarian Jews such as himself could shake off their “shameful Jewish characteristics” caused by long centuries of impoverishment and oppression, and become civilized Central Europeans, a true cultured person along the German lines. Needless to say, Herzl went on to become the father of political Zionism.

Salvador Litvak grew up pretty uninspired by Judaism, before becoming the Accidental Talmudist in his forties. And Jamie Geller became one of the Jewish world’s top chefs and foodies “out of necessity” her mother told me — because she had just gotten married and didn’t know how to cook. She used to use the oven in her New York City apartment as an extra closet for her sweaters. True story.

Do you know the joke about Israelis who relocate to other countries and then return to Israel? It goes like this: They leave Israel as Israelis and come back as Jews — because they discover for the first time what it’s like to not live in a Jewish country. This prompts them to take more pride in Judaism and their Jewishness, and it’s why many Israelis will never wear a Jewish star necklace while living in Israel, yet often wear one while living abroad.

These are just a few of the infinite examples about Jews who have experienced Jewish late blooming, which is usually explored through the lens of dysfunction or as an abnormality. Even in academic research, late bloomers garner little respect.

Nowadays, we are overwhelmingly obsessed with early achievement. We celebrate those who scorch university entrance exams, earn straight A’s, get accepted into Harvard or Stanford, land a first job at Google or Goldman Sachs, win big with their first startup, and are featured on those ubiquitous 30-under-30 lists. In 2014, Time magazine started an annual list of “Most Influential Teens.” Yes, teens.

But precocious achievement is the exception, not the norm. The fact is, we mature and develop at different rates. All of us will have multiple cognitive peaks throughout our lives, and our talents and passions can emerge across a range of personal circumstances, not just in formal educational settings focused on a few narrow criteria of success.

In fact, recent research suggests that we need to modify our understanding of how people mature from adolescence to adulthood. The term that psychologists use for this sort of neurological maturity is “executive function,” which has nothing to do with IQ, potential, or talent. It is simply the ability to see ahead and plan effectively, to connect actions to possible consequences, to see the probabilities of risk and reward.3

These findings validate what previous cognitive research has revealed: Each of us has two types of intelligence, known as fluid and crystallized. Fluid intelligence is our capacity to reason and solve novel problems, independent of knowledge from the past, and it peaks earlier in life. Crystallized intelligence is the ability to use skills, knowledge, and experience — showing swelling levels of performance well into middle age and beyond.

As a teenager and young man, this is exactly what I lacked, and it explains my immaturity and inability to connect with Judaism until my late twenties.

In my experience, Jewish blooming is less correlated with an inherent desire to be Jewish, and more correlated with exposure, or lack thereof. Jewish blooming is most definitely a composite that includes education (and its effectiveness), family background, and familiarity with Jewish history.

“I’ve realized that just because you’re Jewish, that doesn’t mean you necessarily understand or know aspects of our experience as a people,” said Ben Freeman, author of Jewish Pride: Rebuilding a People. “We’re taught about the Shoah (the Holocaust), we’re taught about pogroms, but there’s a lot about our experience that people aren’t aware of. So I think it’s about exploring our history as a people. We have an amazing story and we should learn it.”4

Think about the starting point of late bloomers. In one way or another, they might not have been exposed to Judaism. Or they were exposed, but unsuccessfully. Something went wrong along the way. This closed off their paths of discovery, encouragement, and potential, which then closed the doors to their possibility of a budding Jewish future.

So it makes little sense for the late bloomer to climb back aboard the early-bloomer conveyor belt with renewed determination and hardened resolve, amidst all of life’s trials and tribulations.

Conversely, potential late bloomers ought to find a new path of discovery, and we ought to help them. To make room for Jewish blooming and reblooming, we must move away from the exclusivity of what it means to be a Jew (e.g. born to a Jewish mother, Jewish childhood education, Bar/Bat Mitzvahs) and remove the denominations that plague our Jewish existence.

But, this move away is just the start; we must ultimately move toward what Jews ought to be: intellectually charged with Judaism and Jewishness, and “doing” Jewish on a consistent basis. Or, as the Israeli philosopher Yirmiyahu Yovel put it: “to be personally preoccupied with the question of Jewishness.”

For now, those who do not subscribe to the traditional definitions of Judaism are made to feel like second-class Jews, or even worse: unwelcome at all. We need a Jewish aristocracy of the intellect, not just of inherited Judaism, but of ongoing, compounding Judaism.

When the focus becomes being Jewish, rather than consistently “doing” Jewish, something about Judaism becomes distorted. People who are born Jewish, for example, are viewed or think of themselves as somehow superior, without the prerequisite of having learned and continuously learning about Judaism, Jewish history, Jewish culture, the Jewish state, and so on. This seems like a lousy and unfair rationale for building the future of Judaism and the Jewish People.

A Jewish aristocracy of the intellect will allow us to not be deceived by the world of face-value appearances, such as those of ultra-Orthodox Jews, of Jews with an extra-ordinary amount of tattoos, of LGBTQ+ Jews or Jews of color, or simply of Jews who do not look and act exactly like us.

Instead of a meritocracy that rewards a variety of Jews, we have created a narrow oligarchy mainly composed of a cohort of Jewish early bloomers. Such emphasis on Jewish early bloomers is misplaced and generates a “now or never” paradigm that pushes increasingly more Jews outside of the tent, and prevents some from even entering it at all. It cuts off paths of discovery for later-blooming Jews; trivializes the value of adult Jewish education; and undercuts the majority of us who are potential late bloomers.

Some people are lucky that they have opportunities for Jewish engagement and connection in their early years; perhaps they were born in Israel or moved there during childhood; or their parents had the financial means to send them to Jewish day school and Jewish summer camps; or they had a great Jewish teacher or rabbi. But for the growing majority, Jewish engagement and connection falls through our youthful cracks.

This is why we must celebrate the full range of Judaism and diverse timetables for individual Jewishness. Rather than arbitrarily cutting off paths of discovery at early stages, we ought to be opening paths up. This better corresponds with the fact that each of us develops on an individual schedule in distinctive ways. And it is essential if we are to be a thriving, not just surviving, Jewish People.

“I Was You, ‘Defender of the Palestinians,’ and Now I Want to Puke.” Jewish Journal.

Kathleen Hayes on X

Karlgaard, Rich. “Late Bloomers: The Power of Patience in a World Obsessed with Early Achievement.” Currency.

“Ben Freeman: Where is our pride.” The Jewish Chronicle.

I attended Ethical Culture as a kid and never entered a synagogue until I was an adult. After a long journey into Judaism I have found Chabad to be a great place to learn and pray. They are very accepting of all and the congregants unusually friendly. I have found a home and recommend it to those of less liturgical knowledge like myself.

I remember reading a little book by the Jewish artist, R.B. Kitaj about 15 years ago called "The Second Diasporist Manifesto." Kitaj discussed, among other issues, the huge number of modern artists who were Jews but gave no indication of it. As you read through the book, you kept saying to yourself, "Oh, wow, I had no idea he was Jewish." It made me realize for the first time what an odd thing it was that so much of this world of critics and artists was composed of Jews who all shared a common stance: they were all determined to pretend that being Jewish had little or nothing to do with what they thought or did. Hilarious, really.

One of Kitaj's recommendations to Jews who felt they just didn't fit in to existing categories was a simple one-line injunction: "Be some kind of Jew." Now there was a directive that I could embrace without feeling constrained to be untrue to myself. So simple. Yet it opened a door and changed my life.