A Brief History of Judaism, for the Confused

Far too many people (including Jews) do not know enough about Jewish history, and it is quickly becoming an existential issue.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Astonishingly, many Jews today know only fragments of the Jewish story — holiday customs without origins, slogans without substance, opinions without grounding.

This loss of knowledge is not merely unfortunate; it dangerously produces weakened Jewish identity and participation, a less whole Jewish People, disconnection from the Jewish homeland, and even self-loathing Jews. A people that forgets who it is, where it came from, and why it exists eventually becomes vulnerable to having its story rewritten by others.

Beyond the Jewish world, many people remain profoundly unaware, misinformed, and even brainwashed about Jewish history. Misconceptions abound, whether born of ignorance, cultural bias, or deliberate propaganda, leaving many people confused about who Jews are, where we come from, and the struggles and achievements that have shaped our civilization over millennia.

To understand Judaism, one must begin where Judaism itself begins: According to the Bible, the Jewish story starts not with a nation or a territory, but with a man: Abraham, the first Jew. He was not born Jewish; he became Jewish through a covenant with God, a relationship defined by moral responsibility rather than power or territory. Abraham married Sarah, and together they had a son, Isaac. Isaac married Rebecca, and they had two sons, Jacob and Esau.

Jacob is the crucial figure. He married both Leah and Rachel, and through them became the father of 12 sons. These 12 sons became the 12 tribes of Israel. Jacob himself was renamed “Israel,” a name that literally means “to wrestle with God.” It is an ironic and revealing name. Judaism was never about blind submission; it was about struggle, argument, moral tension, and responsibility. The Jewish People, therefore, are also known as Bnei Yisrael in Hebrew, or the Children of Israel.

Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are known as the patriarchs of Judaism. Alongside them stand the matriarchs: Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah. In other words, Judaism began as a family, not an empire.

One of Jacob’s sons, Joseph, was sold by his brothers and eventually rose to power in Egypt as an advisor to Pharaoh. When famine struck the Land of Israel, the entire family descended into Egypt for survival.

In Egypt the Israelites multiplied and prospered. According to the biblical narrative, the Israelites became prosperous in ancient Egypt largely because of Joseph, who became Pharaoh’s chief administrator and oversaw Egypt’s economic system during seven years of abundance and seven years of famine. His policies turned Egypt into the most stable and food-secure power in the region, drawing surrounding populations to it for survival.

Their success, however, depended on political stability. When a new Pharaoh arose who “did not know Joseph,” the Israelites lost their protection and were enslaved. Their prosperity, rapid population growth, and social cohesion came to be seen as a threat rather than an asset. What had once enabled their flourishing became the rationale for their enslavement, setting the stage for the Exodus and embedding a recurring pattern in Jewish history: contribution, success, vulnerability, and scapegoating following political change.

The Egyptian regime imposed forced labor, compelling the Israelites to build store cities such as Pithom and Raamses and to perform hard labor meant not only to exploit them economically, but to break their spirit and slow their population growth. This was not random cruelty; it was state policy, rooted in fear of a successful, growing, and distinct minority.

The exact length of Israelite slavery in Egypt depends on how one reads the biblical and rabbinic sources. The Torah speaks of a 400-year period tied to Abraham’s prophecy that his descendants would be “strangers in a land not their own,” but this includes time before actual enslavement, beginning with Isaac’s birth and the family’s early sojourns. Rabbinic tradition more precisely holds that the Israelites were in Egypt for 210 years, with slavery intensifying only in the later portion of that period — likely for several generations rather than the entire stay.

This distinction matters. Jewish memory does not portray slavery as our natural condition, but as a catastrophic reversal of fortune caused by political change.

Eventually, Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt in what became known as the Exodus. This was not merely an escape from slavery; it was the birth of a people with purpose. At Mount Sinai, the Israelites received the Ten Commandments. This moment is where Judaism transformed from ancestral tradition into a fully structured system: laws, ethics, rituals, governance, and decision-making frameworks.

Judaism now had rules not just for belief, but for life itself.

During the 40 years of wandering in the desert, the Israelites carried a portable sacred center: the Mishkan, a tent housing the Holy Ark. This was Judaism before permanence, a holiness that moved with the people. (Yes, this is the same ark popularized, inaccurately but memorably, in the movie “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”)

Rabbi Mordechai Kaplan later described Judaism during this era — and, in many ways, ever since — through what he called the Three B’s:

Believing – Faith in the foundational ideas unique to Judaism

Behaving – Living through commandments (Shabbat, prayer, dietary laws, ethical conduct)

Belonging – Being part of the Jewish People by birth, history, and shared destiny

Around 1270 BCE, under the leadership of Joshua, the Jewish People entered the Land of Israel and established a national home. At that stage, this home was called the Land of Israel and divided among the 12 tribes. Each tribe received its own territory. The region that would later be known as Judah/Judea was the portion allotted to the tribe of Judah, primarily in the southern highlands, including Jerusalem.

The term Judea only emerged later, after the Israelite monarchy split following King Solomon’s death (10th century BCE). At that point, the northern kingdom was called Israel and the southern kingdom was called Judah. After the northern kingdom was destroyed by the Assyrians in the 8th century BCE, Judah became the primary surviving Jewish polity, and its name eventually came to represent the Jewish People and our land as a whole. Through Greek and Roman usage, Judah became Judea, and from that word we get the term “Jew.”

Then, in the 10th century BCE, the Holy Temple was built in Jerusalem. This was a turning point. Holiness shifted from portable to stationary. The Temple became the spiritual, moral, and communal center of Jewish life. Jews were not required to live exclusively in the land, but they were commanded to make pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year for Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot. Jewish time, Jewish space, and Jewish purpose revolved around this center.

Judaism during this period was deeply structured: how to mark days and seasons, how to live ethically, how to celebrate joy, mourn loss, conduct business, raise children, and honor God. The Temple anchored Jewish life.

In 586 BCE, the First Temple was destroyed by the Babylonian Empire under King Nebuchadnezzar. Jerusalem was conquered, the Temple burned, and much of the population exiled. This was not just military defeat; it was spiritual rupture. The heart of Jewish life was torn out.

Seventy years later, the Jews returned and rebuilt the Temple through imperial permission, political realism, and religious persistence — and that distinction is essential to understanding Jewish history.

After the First Temple was destroyed and much of the Jewish elite was exiled, Jewish sovereignty ended. There was no successful revolt against Babylon. Instead, history turned on a regime change outside Jewish control. In 539 BCE, the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon. Unlike the Babylonians, the Persians pursued a policy of allowing exiled peoples to return to their homelands and restore local religious institutions as a way of stabilizing the empire.

Cyrus issued a decree permitting the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple. This was not a declaration of independence; Judah remained a small, semi-autonomous province within the Persian imperial system. A limited number of Jews returned at first. The rebuilding effort faced significant local opposition, economic hardship, and long delays. Construction stalled multiple times and resumed only after prophetic encouragement from Haggai and Zechariah, who reframed the project not as a political triumph but as a religious obligation.

The Second Temple was completed around 516 BCE, roughly 70 years after the destruction of the First Temple. It was a moment of renewal, but also of humility. Jewish sovereignty was not restored; the Temple stood by the grace of an empire. This shaped Judaism profoundly, teaching Jews how to survive, rebuild, and sustain religious life without political power, a skill that would define the next 2,000 years of Jewish history.

After the Second Temple was rebuilt, Judea passed from empire to empire: first the Persians, then the Greeks following Alexander the Great’s conquests. Over time, Greek (Hellenistic) culture spread throughout the region. Many Jews adopted elements of it voluntarily, while others resisted. This cultural tension between Jewish tradition and assimilation into a dominant foreign civilization became the central fault line of the era.

The crisis came in the second century BCE, under the Seleucid Greek king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Unlike earlier rulers, Antiochus did not merely govern Judea; he attempted to eradicate core Jewish practices. He outlawed circumcision, Shabbat observance, and Torah study, and desecrated the Temple by installing a pagan altar. This was not a political dispute; it was an assault on Jewish religious existence itself.

The Jewish revolt circa 167 to 160 BCE began as a guerrilla uprising led by Mattathias and his sons, most famously Judah Maccabee. Against overwhelming odds, they defeated the Seleucid forces, retook Jerusalem, and rededicated the Temple — the event commemorated by Chanukah. This was a rare moment in Jewish history: a successful religious-military rebellion that restored Jewish control over Jewish worship.

The revolt eventually led to the establishment of the Hasmonean dynasty, granting Jews something they had not had since the Babylonian destruction: political sovereignty. For roughly a century, Judea was an independent Jewish state.

But here is the crucial connection to the later fall of the Second Temple: The Hasmonean period itself planted seeds of internal division. The merging of kingship and priesthood, forced conversions, territorial overreach, and growing factionalism fractured Jewish society. Rival Jewish leaders eventually invited Roman intervention into Judean affairs, an intervention that ended Jewish independence and set the stage for Roman rule.

Then, in the year 70 CE, following a Jewish revolt against Roman rule, the Romans destroyed the Second Temple. Jerusalem was devastated, Jews were expelled from the city, and the area was renamed “Syria Palaestina” (today known as “Palestine”). According to Josephus, a Roman-Jewish historian and military leader, over a million non-combatant Jews died, and tens of thousands were enslaved.

Internal Jewish division played a major role in the fall of the Second Temple — not as the sole cause, but as a critical accelerant that weakened Jewish society at the exact moment it needed cohesion. By the first century CE, Judea was not a unified community facing Rome together. It was deeply fragmented religiously, politically, and socially. Different Jewish groups disagreed not only about theology, but about how to respond to Roman rule.

The Sadducees, largely drawn from the priestly and aristocratic elite, were closely tied to the Temple and often cooperated with Roman authorities to preserve stability and their own status. The Pharisees, whose influence lay among the broader population, emphasized law, study, and daily religious life rather than Temple ritual alone. The Essenes withdrew from mainstream society altogether, seeing it as corrupt, while radical groups such as the Zealots believed armed rebellion against Rome was both inevitable and divinely mandated.

These divisions became catastrophic during the Great Jewish Revolt from 66 to 70 CE. Jewish factions did not merely argue; they fought each other. Rival militias battled for control of Jerusalem. In one of the most devastating acts of self-sabotage, Jewish extremists destroyed their own food supplies to force the population into continued rebellion, even as Roman legions closed in. Instead of presenting a united front, Jerusalem descended into civil war while under siege.

Rabbinic tradition later framed this internal collapse through the concept of sinat chinam: baseless hatred among Jews. While this is a moral lens rather than a military analysis, it captures something historically real: the breakdown of trust, shared purpose, and collective responsibility. Rome was overwhelmingly powerful, but Jewish disunity ensured that resistance was chaotic, unsustainable, and ultimately futile.

When the Romans destroyed the Second Temple in 70 CE, they crushed a revolt, but they also encountered a society already tearing itself apart from within. The lesson absorbed by later Jewish tradition was stark: External enemies can destroy a people’s buildings, but internal division can hollow out a people before the walls ever fall.

And, so, Temple-based Judaism was crushed. Sacrificial worship ended. Political sovereignty vanished. Exile became the dominant condition of Jewish life.

But Judaism did not die; it transformed. Study replaced sacrifice. Synagogues replaced the Temple. Rabbis replaced priests. They captured stories, wrote down the Oral Law (the Mishnah) so it could go hand-in-hand with the Written Law (the Torah), and codified a system of Jewish law (halacha) which became the defining feature of Judaism. Shabbat, holidays, prayer, and ethical law were reinterpreted to function without sovereignty or a physical center.

Even so, Jewish memory never let go of Judea (the ancient heartland of Jewish civilization) and Jerusalem (our capital). This is why places like Judea and Samaria matter so deeply to Jewish history and identity. (These regions were later renamed “the West Bank” by Jordanians in the 20th century, but their Jewish significance predates modern geopolitics by millennia.)

Of course, rabbis differed on how to interpret the laws and stories, and different schools of thought developed around the greatest of rabbis. Despite these differences, being Jewish was still defined by Kaplan’s Three B’s: believing, behaving, and belonging.

And yet, while Judaism remained one civilization, its historical experience began to fracture geographically. Exile did not send Jews to a single place, nor did it expose them to a single culture. Instead, Jewish communities spread across vastly different worlds, each with its own languages, political systems, social norms, and pressures. Over centuries, this produced distinct Jewish experiences, even as the underlying structure of Judaism remained intact.

Broadly speaking, two major centers of Jewish life emerged. One developed across Iberia, the Middle East, and North Africa, in lands that would later become part of the Islamic world. The other took root in Europe, particularly in Christian societies. These were not merely different addresses; they were radically different civilizational environments. Jews carried the same texts, rituals, and legal framework into both worlds, but how Judaism was lived, defended, and expressed diverged in meaningful ways.

In the Middle East and North Africa, Jews often lived as protected minorities under Muslim rule (known in Arabic as dhimmis), and were granted communal autonomy in exchange for political subordination. Jewish life there tended to remain closer to Hebrew and Arabic, embedded within societies that, while discriminatory, largely tolerated Jewish religious continuity.

In Europe, by contrast, Jews existed as perpetual outsiders in Christian civilizations that frequently defined themselves in opposition to Judaism itself. This produced a far more volatile experience: cycles of restriction, expulsion, violence, and forced isolation, alongside moments of extraordinary intellectual and cultural creativity.

But, as European societies embraced secular Enlightenment ideas, Jews increasingly entered public life, contributing to the scientific, philosophical, and artistic currents shaping the broader culture around them.

In the 18th century, the observant Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn challenged longstanding assumptions about religious life and practice. His revolutionary ideas gained recognition among Enlightenment thinkers, including Immanuel Kant. As European societies began to relax restrictions — allowing Jews to leave ghettos and shed identifying clothing — Jewish life adapted to the changing world. This era gave rise to Reform Judaism in the early 1800s, which sought to reinterpret tradition for modern times while preserving core principles, giving individuals the freedom to determine which aspects of their heritage to embrace.

Reform synagogues in Germany, for example, changed their practices to emulate Christian society, like introducing choirs and organs for music, and allowing mixed seating of men and women. This Jewish Reformation was exported to emerging parts of the West, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and South Africa. By 1880, for example, 90 percent of U.S. synagogues were Reform.

In 1897, the legendary Hebrew essayist Ahad Ha’am wrote: “It is not only Jews who have come out of the Ghetto: Judaism has come out, too. For Jews the exodus is confined to certain countries, and is due to toleration; but Judaism has come out (or is coming out) of its own accord wherever it has come into contact with modern culture.”

But Ha’am also foresaw: “When it leaves the Ghetto walls it is in danger of losing its essential being or — at best — its national unity: it is in danger of being split up into as many kinds of Judaism, each with a different character and life, as there are countries of the Jewish dispersion.”

In the emerging West, many Jews were still second-class citizens, which included quotas that universities had with regard to the number of Jews they would accept, lack of access to country clubs, and laws disallowing Jews to own land. In parts of the Arab world and in Europe, it was even worse. Pogroms and state-sponsored antisemitism were regular occurrences.

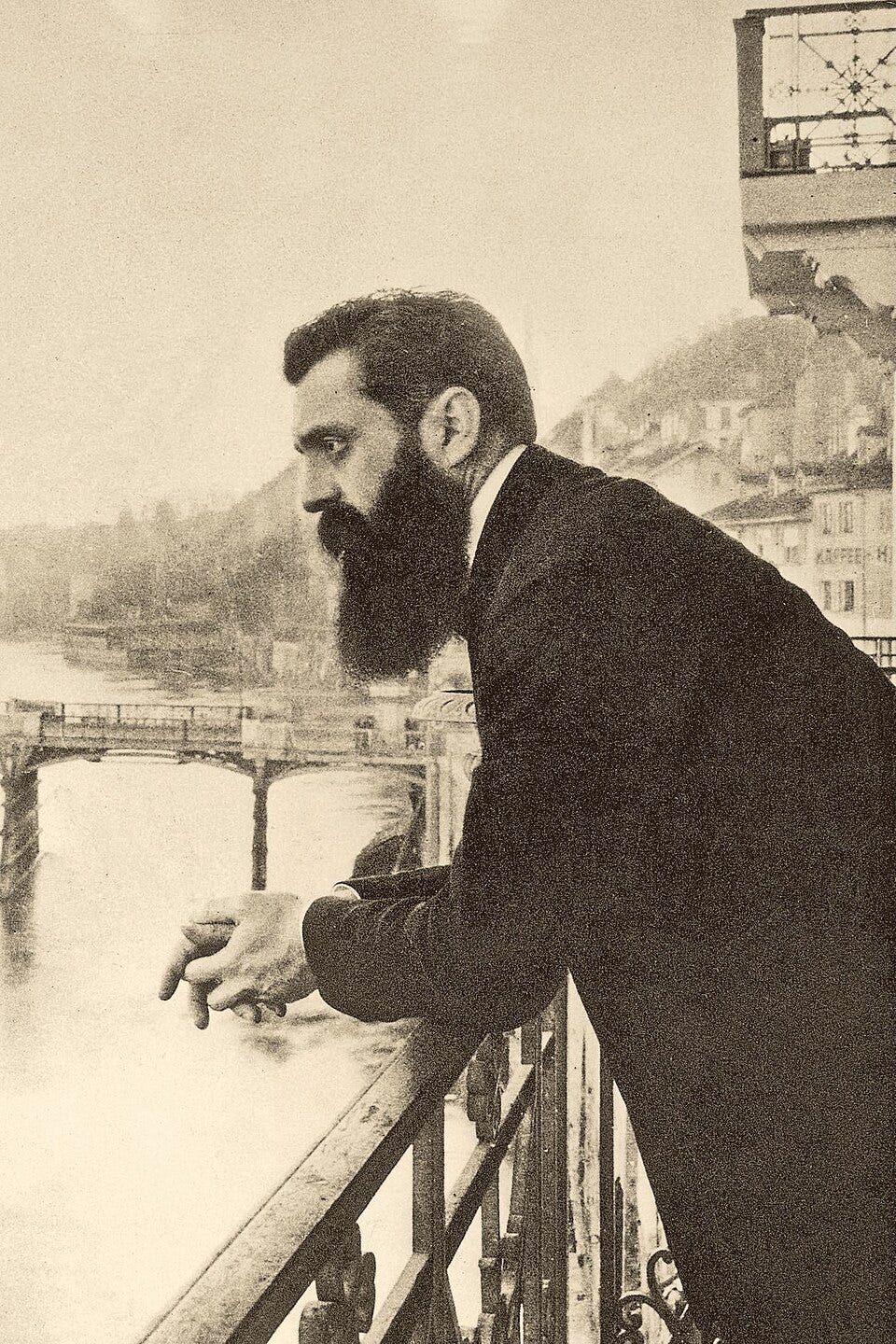

In fact, the Dreyfus affair in France, during which a Jewish military officer was falsely accused of treason in 1894, was one noteworthy example of state-sponsored antisemitism because it led to the formation of the modern political Zionist movement by Theodor Herzl. This movement highlighted the need for Jews to have their own independent state in the Land of Israel, where pioneering Jews had already been laboring to settle the land for nearly 100 years. (A Jewish presence in the area remained even after the Romans killed, enslaved, and exiled our ancestors.)

In the 1890s, Herzl infused Zionism with a new ideology and practical urgency, leading to the First Zionist Congress in Switzerland in 1897, which created the World Zionist Organization. From 1897 to 1901, the Zionist Congress met annually, and thereafter biennially. By the Sixth Congress, Herzl succeeded in arousing, establishing, and leading a dynamic and developing movement.

Herzl considered antisemitism to be an eternal feature of all societies in which Jews lived as minorities, and that only a separation could allow Jews to escape eternal persecution. “Let them give us sovereignty over a piece of the Earth’s surface,” he wrote, “just sufficient for the needs of our people, then we will do the rest!”

Herzl contemplated two possible destinations for a Jewish state, Argentina and Palestine, preferring Argentina for its vast and sparsely populated territory and temperate climate. Ultimately, he conceded that Palestine would have greater attraction due to the Jews’ historic ties with this area.

The official beginning of the construction of the “New Settlement” in Palestine is usually dated to the arrival of the Bilu group in 1882, which commenced the first aliyah. In the following years, Jewish immigration to Palestine started in earnest. Most immigrants came from the Russian Empire, escaping the frequent pogroms and state-led persecution in what are now Ukraine and Poland. They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe.

At the time, Palestine was under Ottoman control (from 1516 to 1917 in total). Previously it was controlled by the Byzantines, the Arabs, the Crusaders, the Mamluks, and other empires — never existing as a unique, sovereign entity.

Over time much of the existing population in Palestine adopted Arab culture and language and converted to Islam. Therefore, the region was not originally Arab. Its Arabization was a consequence of the gradual inclusion of Palestine within the rapidly expanding Islamic Caliphates established by Arabian tribes and their local allies — meaning Arabization is a colonial force and Jewish return is a form of decolonization.

For several centuries during the Ottoman period, the population in Palestine declined and fluctuated between 150,000 and 250,000 inhabitants. It was not until the 19th century that rapid population growth occurred, fueled by the arrival of Egyptians, Algerians, Bosnians, and Circassians, as well as Jewish immigrants — the latter of whose efforts developed a modern economy, eradicated diseases such as malaria, and made the region significantly more habitable.

The term “Palestinian” was first introduced in 1898 by Khalil Beidas in the Arabic translation of a Russian work on the Holy Land. After that, its usage gradually spread so that, by 1908, with the loosening of censorship controls under late Ottoman rule, a number of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish correspondents writing for newspapers began to use the term with great frequency in referring to the “Palestinian people,” “Palestinians,” the “sons of Palestine,” and “Palestinian society.”

Palestinian national consciousness did not begin to emerge until well into the 1900s. Still, many local Arabs considered Palestine “as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds” — an official stance adopted at the 1919 First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations.

Violence between Jews and Arabs in the region erupted over the next three decades. Even then, the Jews stood ready to share the land with the Arabs as part of a two-state solution, starting with a proposal in the 1936 Peel Commission, and again with the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.

Palestinian Arab leadership outright boycotted UN deliberations that led to this Partition Plan, rejecting it wholesale and indicating that they would reject any other plan of partition. This has largely been the Palestinian posture ever since, backed by various Arab states that continue to manipulate “the Palestinians” as a pawn to advance their greater geopolitical goals.

After World War II and the destruction of Jewish life in Europe, modern Zionism became urgent (even existential) in the thinking about a Jewish national state. The movement was eventually successful in establishing the State of Israel on May 14, 1948, as a renewed homeland for the Jewish People.

I knew most of this, but the part that jumps out at me is the troubles we brought and still bring upon ourselves by dissension within Jewry. It was ever thus.

This is great! Thank you. I recently gave a presentation to peers in the CCRC where I live about Hanukkah, and began not quite as "in the beginning" as you did with patriarchs etc., but more as tribes who coalesce and became a kingdom and went to the destruction of 70CE and the Romans renaming Judea. People were so appreciative; Jewish history is long and complex! Now I have the second half available to me from your writing! I also began with 4 points that any discussion of Jews should keep in mind: Judaism is a religion, Jews is a peoplehood; History-Jews live their history--historical events remembered and incorporated into who we are; Diversity--we have small numbers but much diversity in all arenas of our existence;-- so that all answers to questions begin with "it's complicated" or "it depends." I agree with you--knowing our history IS an existential issue for us in our time.