Can $15 million fix antisemitism? Probably not.

A $15-million Super Bowl awareness campaign can signal virtue, but it cannot substitute for building Jewish strength, identity, and continuity.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Ahead of today’s Super Bowl game, New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft unveiled a new national ad through his Blue Square Alliance Against Hate.

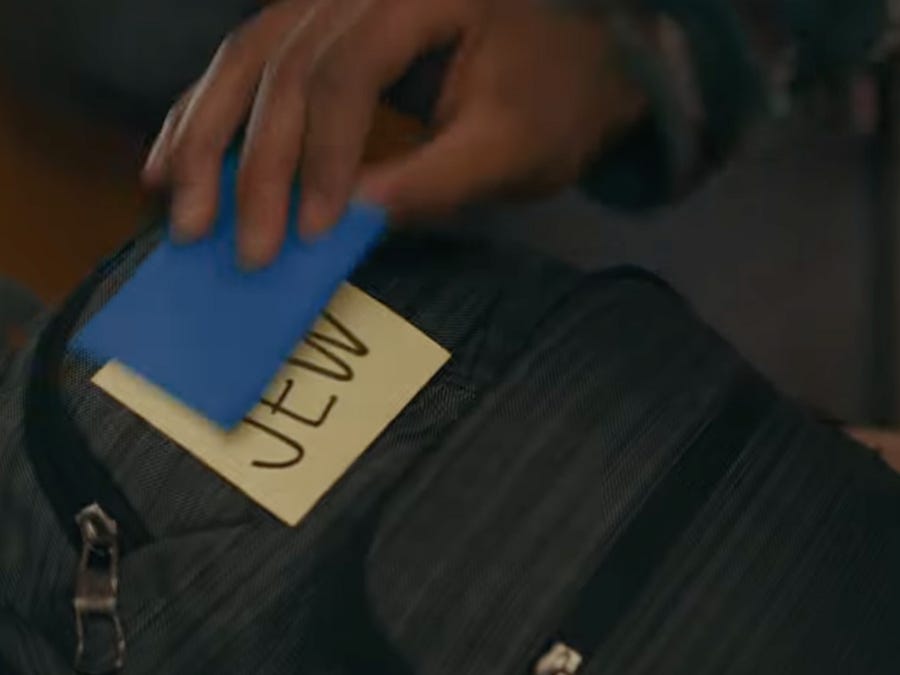

The spot, titled “Sticky Note,” is simple, polished, and emotionally calibrated for prime time. A Jewish student walks the halls of his school unaware that classmates have stuck a degrading antisemitic note to his backpack. Another student notices, peels it off, and replaces it with a blue square, the campaign’s symbol. He places one on his own chest as well, and silently walks alongside the boy.

It’s a clean metaphor. Hate can be covered. Solidarity can be signaled. Courage can be quiet. And for roughly $15 million, the cost of a Super Bowl ad slot, you can beam that message into more American living rooms than any synagogue, Jewish school, or community organization ever could.

But since premiering online this week, the ad has also triggered a wave of excoriating reactions, many from Jews themselves. Critics have panned it as disconnected from the lived reality of contemporary Jewish teens, who are far more likely to encounter antisemitism online, on social media, and in the context of anti-Israel activism than via anonymous sticky notes in school hallways. Others dismissed it as a waste of money, or as yet another cliched portrayal of Jewish weakness at a moment when Jews are craving strength, confidence, and pride.

Columnist Liel Liebowitz, while expressing respect for Kraft personally, went further, calling it “almost impossible to imagine a more retarded ad.” Liebowitz argued that the Jewish response to antisemitism should project power and resilience, not fragility.

“If I had ten million dollars to spend on a Super Bowl ad,” he wrote on X, later expanding the argument into an essay, “I’d just show a bunch of exploding beepers, dead Hamas and Hezbollah leaders, hot Israeli girls with guns, and the caption ‘F–k Around, Find Out.’ But hey, why go with Jewish power and pride when quivering victimhood mixed with the worst of social media clicktivism is exactly what some committee of overpaid PR pros and professional Jewish org types thought would work wonders?”

Shabbos Kestenbaum, a Harvard University alum who emerged as a prominent Jewish voice after October 7th, echoed a similar critique: “American Jews: If you are spending millions to ‘fight antisemitism’ instead of building Jewish life,” he wrote, “you are both out of touch with the needs of Gen Z Jews and have not learned the lessons of post–October 7th Jewry. Fund Jewish day schools, not Super Bowl ads.”

Others took aim less at the tone and more at the substance of the campaign itself, particularly the Blue Square Alliance’s central symbol, which encourages people to wear or post a blue square to signal opposition to antisemitism. “All you have to do is post a blue square, and you’re good,” tweeted pro-Israel influencer Isaac de Castro. “You don’t have to confront anti-Zionism or the neo-Nazi right. You don’t have to say anything at all. How does this help combat antisemitism?”

This year’s commercial marks the third consecutive Super Bowl appearance for Kraft’s organization. In 2024, it aired what was believed to be the first-ever Super Bowl ad explicitly focused on antisemitism, featuring a former speechwriter for Martin Luther King Jr. Last year, it returned with a spot starring Tom Brady and Snoop Dogg, urging viewers to stand up to “all hate,” without mentioning Jews at all — an ad that ran alongside a separate commercial by Kanye West promoting swastika T-shirts.

Which brings us to the deeper, more uncomfortable question beneath the media strategy, the symbolism, and the backlash: Can money buy Jewish support? Or, more precisely, can awareness campaigns (however well-funded and well-intentioned) actually combat antisemitism in a meaningful, durable way?

Awareness matters. Symbols matter. Non-Jewish allies matter deeply. But antisemitism is not primarily a PR problem. It is a civilizational, cultural, educational, and identity problem — one that cannot be solved by fancy advertising. If we want to do more than momentarily tug at heartstrings, if we want to build something that lasts longer than a news cycle, we need to focus less on optics and more on substance.

Here are a few ways to actually combat antisemitism, none of which can be purchased in a single media buy:

1) Sharpening Your Jewish Pencil

The Israeli philosopher Yirmiyahu Yovel offered a broad and charitable definition of a Jew: someone who is “personally preoccupied with the question of Jewishness.” Embedded in that definition is motion — doing, questioning, engaging, and continually deepening one’s intellectual and emotional relationship with Judaism and, by extension, Israel. That is what I mean by “sharpening your Jewish pencil.”

The more I engage with Judaism, the more I come to understand just how historically, geographically, and materially deep Jewish complexity runs. While many people attempt to simplify Judaism by squeezing it into a single box (religion, ethnicity, culture), I am constantly reminded that it is far more oceanic than that. Judaism is not reducible; it is accumulative.

Whether your interests lean toward religion and spirituality, history, wisdom and philosophy, culture and lifestyle, peoplehood and society, travel and tourism, or some combination of these, Judaism offers an almost endless series of rabbit holes to explore. The sharper our Jewish pencils become, the harder it is for antisemitism to flatten us into caricatures, and the harder it is for us to internalize those caricatures ourselves.

2) Being a Good Jewish Ancestor

The Talmud tells the story of Honi the Circle Maker, who once saw a man planting a carob tree. Honi asked how long it would take for the tree to bear fruit. “Seventy years,” the man replied. Honi then asked, somewhat incredulously, whether the man expected to live another seventy years. The man paused and answered simply: “I found carob trees in this world planted for me by my ancestors, so I am planting these for my descendants.”

One of our core missions as Jews, I believe, is to keep planting carob trees. The Māori language captures this idea beautifully with the word fakaapaapa — the understanding that we exist within a vast intergenerational chain stretching deep into the past and long into the future.

The late Rabbi Noah Weinberg articulated a practical expression of this responsibility:

“If you want to feel what your Jewish ancestors felt, learn one chapter of Mishnah by heart. That is Jewish culture at its roots. The beauty of it will get to you. You will appreciate Torah from Sinai. You will understand what the Jewish People are truly about.”

Being a good Jewish ancestor also requires an honest awareness of our privilege. This is not to say that the world is, or ever will be, perfect for Jews. But everything is relative. Compared to just a few generations ago, let alone centuries prior, many Jews today enjoy unprecedented freedom to live openly Jewish lives while also participating fully in broader society.

That reality did not emerge by accident. It exists because countless Jews before us did not have those options. Some survived by staying under the radar. Others assimilated out of necessity, leaving parts of their Judaism behind. Today, many of us can be openly Jewish and fully integrated at the same time. That is a fragile achievement, and Jewish history teaches us that nothing, no matter how stable it seems, is guaranteed.

This is not about guilt. It is about stewardship. Our responsibility is to nurture this moment so future generations can inherit it as well — both in Israel and throughout our diaspora. To speak freely as Jews, to visit Jewish sites across the world, to experience our indigenous homeland in modern-day Israel — these are privileges earned by ancestors who planted carob trees knowing they would never sit in their shade.

3) Learning Modern-Day Hebrew

The revival of Hebrew as the official language of the State of Israel is nothing short of miraculous. It fuses divinity and antiquity with the immediacy of daily life, serving as a living reminder of both the survival of the Jewish People and the rebirth of our indigenous homeland.

Growing up, I assumed Hebrew belonged mainly in synagogue halls and prayer books. Today, I find immense joy in hearing it everywhere else: on Israeli streets, in music and theater, on television and in film. Hebrew across life’s crosshairs feels like a declaration that Jewish continuity is not theoretical; it is lived.

Hebrew is to Judaism what hands and fingers are to sign language. It tells the story of a people scattered across continents yet bound together as a single family, a nation repeatedly marked for destruction, sometimes partially returning home, sometimes remaining in the Diaspora. Some Jews stayed religious, embedded in divine Jewish life. Others assimilated, becoming fully part of their surrounding cultures while still carrying something unmistakably Jewish within them.

Is mere Jewish identification enough to hold this family together today and into the future? I am skeptical. Jewish journeys have become increasingly disparate, sometimes barely connected by shared language, ritual, or memory.

Hebrew offers a unifying counterweight. It did so during the years leading up to and following Israel’s 1948 declaration of statehood, when Jews arrived from Europe, the Middle East, and beyond — speaking Polish, Persian, Arabic, English, and dozens of other languages. Hebrew enabled complete strangers, who looked, smelled, and behaved differently, to build a shared society now defined by bravery, resilience, family, service, education, innovation, and creativity.

In an age of hyper-individualism, rising assimilation, and growing Jewish disunification, reclaiming Hebrew is not nostalgic; it is strategic. It is a way to vitalize and revitalize Jewish peoplehood in a world that increasingly pulls us apart.

4) Sharing Judaism With the World

Judaism has survived, often heroically, by being insular. But survival is not the same as flourishing. To truly thrive, both individually and collectively, we need healthier, more constructive relationships with our non-Jewish families, friends, and communities.

This may sound controversial, but in an open, globalized, hyperconnected world, a rigid “members-only” posture is no longer serving the Jewish People. That does not mean turning synagogues into free-for-alls, diluting conversion standards, or redefining who counts as a Jew. It means recognizing that technology, media, e-commerce, and emerging digital platforms can offer unprecedented access to Jewish life, culture, peoplehood, and Israel — for Jews and non-Jews alike.

Making Judaism more accessible is not a threat to Jewish integrity; it is an expression of Jewish purpose. Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, once illustrated this to a Russian-Israeli scientist by comparing Jews to the sun:

“What is the unique quality of the sun?” he asked. “Its ability to give light. What if the sun had the same heat and energy but did not radiate? There are such stars — black holes — from which not even light can escape. If the sun were a black hole, whom would it benefit? So it is with the Jew, whose function is to radiate, to illuminate, to better others. Without this, one becomes a black hole — when one was created to be a sun.”

Gentry liberals, esp the wealthy and/or those who were raised in the 20th century, are NEVER ever ever going to face the reality and causes of our current eruption of Jew hate, mostly because they will never relinquish what's maybe the most influential post-WW2 idea, that sentimental therapeutic humanitarianism is a balm that can heal all wounds (people just need to learn and to feel seen! and the higher we can raise their self-esteem, the nicer they'll be), but also because this would require a level of social conflict and courage that they're simply too fat and content to risk.

If you have a sewage spill or an oil leak, you go straight to the cause and fix it there. In this case, the toxic sewage leak is coming directly from our most prestigious universities, the Qatar-aligned madrassas who are the home office of Islamo-Marxist jihadism and who've given the world all the greatest hits of Anti-Zionism—settler-colonial imperialist apartheid genocidal ethnostate etc. This is the root of modern Jew hate, this state-subsidized idea that Israel is the world's most evil and most illegitimate state, and that Justice requires its eradication.

If you wanted real bang for you buck, how about a simple illustration of the most shocking and repulsive events that recently took place in modern America: the celebrations of the 10/7 massacre that broke out across the Ivy League, the tearing down of hostage posters, the disgusting quotes by dozens of academics that would have them chased out of polite society if uttered about any other minority. Just a simple montage of all the Ivy League students screaming in bloodlust with some quotes (maybe even one from Mr. Mamdani Sr) showing how infested with Jew hate our culture has become. You need to rub the hatred into the faces of the Jew haters, let them feel the shame they're always desperate to smear on others.

Kraft has brought a Hallmark card to a gunfight, but I would expect nothing else. It's hard for people to face and accept what's become of our most prestigious universities, esp to a high-achieving normie who's been saluting them like the flag their entire lives. They still imagine they live in the world they grew up in, but that's dead and irrelevant, as this Super Bowl ad will be by morning.

Kraft doesn’t understand. It’s so so so much more effective to show a video that informs everyone that Jews are indigenous to the land of Israel, as Bill Maher has done very recently; or how many inventions Israelis and Jews are responsible for that we use and couldn’t live without; or how Jews help other ethnic and religious groups all over the world, including Gazans, Muslims, and Arabs; or even proof of the Holocaust using actual evidence with a variety of commentators that are highly regarded famous figures who are not Jewish. What a waste of $15 million that could have had a tremendous positive impact.