Efforts to protect younger Jews are backfiring.

When we raise kids unaccustomed to facing anything on their own — including antisemitism — the Jewish People are threatened.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Many young Jews, particularly around the world, seem to lack resilience nowadays.

Generally, we know that people build resilience through the pursuit and endurance of challenges.

“Pain is not just a teacher,” wrote Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist and bestselling author. “It’s a relic — a reminder of your ability to withstand adversity.”

Yet many of today’s young Jews are enclosed in environments which over-emphasize “safe spaces” — only making them less resilient — or what I will call “fragile Jews.”

“Fragile Jews” are on the verge of writing off Judaism and their Jewishness because they tend to lack deep-seated Jewish pride and dignity; they likely have a feeble or non-existent relationship with Israel and Israeli culture, society, and history; they seek mission and purpose seemingly everywhere except Judaism; or some combination thereof.

As a result, in our post-October 7th world, many young Jews are having a difficult time finding the time, space, and confidence to proudly and unequivocally stand up for the Jewish People and our Jewish homeland.

The “fragile Jew” reminds me of, albeit under different circumstances, many Jews before the State of Israel, who displayed “an older Jewish pattern of relying on powerful Gentile guardians, whose ongoing protection must be secured through the techniques of political maneuver and intrigue,” according to Eli Spitzer, headmaster of a Hasidic boys’ school in London.1

But the State of Israel, founded in 1948, transformed an extraordinary amount of Jews. It made these Jews more ferocious, more unapologetic, more daring, more adventurous, more optimistic, more heroic, more glorious. And it led to a conception of “the New Jew, whose soul and character would be purged of the disfigurements impressed upon the Diaspora Jew by millennia of exile,” wrote Spitzer.

“Each Zionist thinker differed in identifying which aspects of the Old Jew were particularly objectionable, and thus which aspects of the New Jew were most crucial to inculcate,” added Spitzer, “but all agreed that something had gone drastically wrong in Jewish history which went far beyond the persecution that Jews had suffered at Gentile hands.”

Yet, “the Old Jew” is making a comeback of sorts. The result? Many of today’s young Jews are more insecure, more easily offended, and more reliant on others. They have been taught to seek authority figures to solve their problems and shield them from discomfort, a condition sociologists call “moral dependency.”

To be sure, our elders have had the best of intentions. But efforts to protect younger Jews appear to be backfiring. When we raise kids unaccustomed to facing anything on their own — including antisemitism — the Jewish People are threatened.

How did we come to raise a generation of Jews who cannot handle the basic challenges of being and doing Jewish? And more importantly, how can we prevent “fragile Jews” from becoming an all-out epidemic among the Jewish People?

Here are four places to start:

1) Practice Jewish aristocracy of the intellect.

To make room for Jewish strength and fortitude, we must move away from the exclusivity of what it means to be a Jew (e.g. born to a Jewish mother, Jewish childhood education, Bar/Bat Mitzvahs) and remove the denominations that plague our Jewish existence.

But this move away is just the start; we must ultimately move toward what Jews ought to be: intellectually charged with Judaism and Jewishness, doing Jewish on a consistent basis, and being a good Jewish ancestor. Or, as the Israeli philosopher Yirmiyahu Yovel put it: “to be personally preoccupied with the question of Jewishness”

For now, those who do not subscribe to the traditional definitions of Judaism are made to feel like second-class Jews, or even worse: unwelcome at all. We need a Jewish aristocracy of the intellect, not just of inherited Judaism, but of ongoing, compounding Judaism.

When the focus becomes being Jewish, rather than consistently doing Jewish, something about Judaism becomes distorted. People who are born Jewish, for example, are viewed or think of themselves as somehow superior, without the prerequisite of having learned and continuously learning about Judaism, Jewish history, Jewish culture, the Jewish state, and so on. This seems like a lousy and unfair rationale for building the future of Judaism and the Jewish People.

A Jewish aristocracy of the intellect will allow us to not be deceived by the world of face-value appearances. In today’s Jewish world, many of us are “prisoners” to our own definitions and denominations of what it means to be and do Jewish. We surround ourselves with other like-minded “prisoners” and distance ourselves from differing ones.

What we need to do, instead, is leave our proverbial caves so we can begin to understand all other forms Jews — that is, why and how others Jews be and do Jewish. The goal is not to adopt their means and methods, but to develop deeper empathy and understanding in pursuit of a greater, more balanced “truth.”

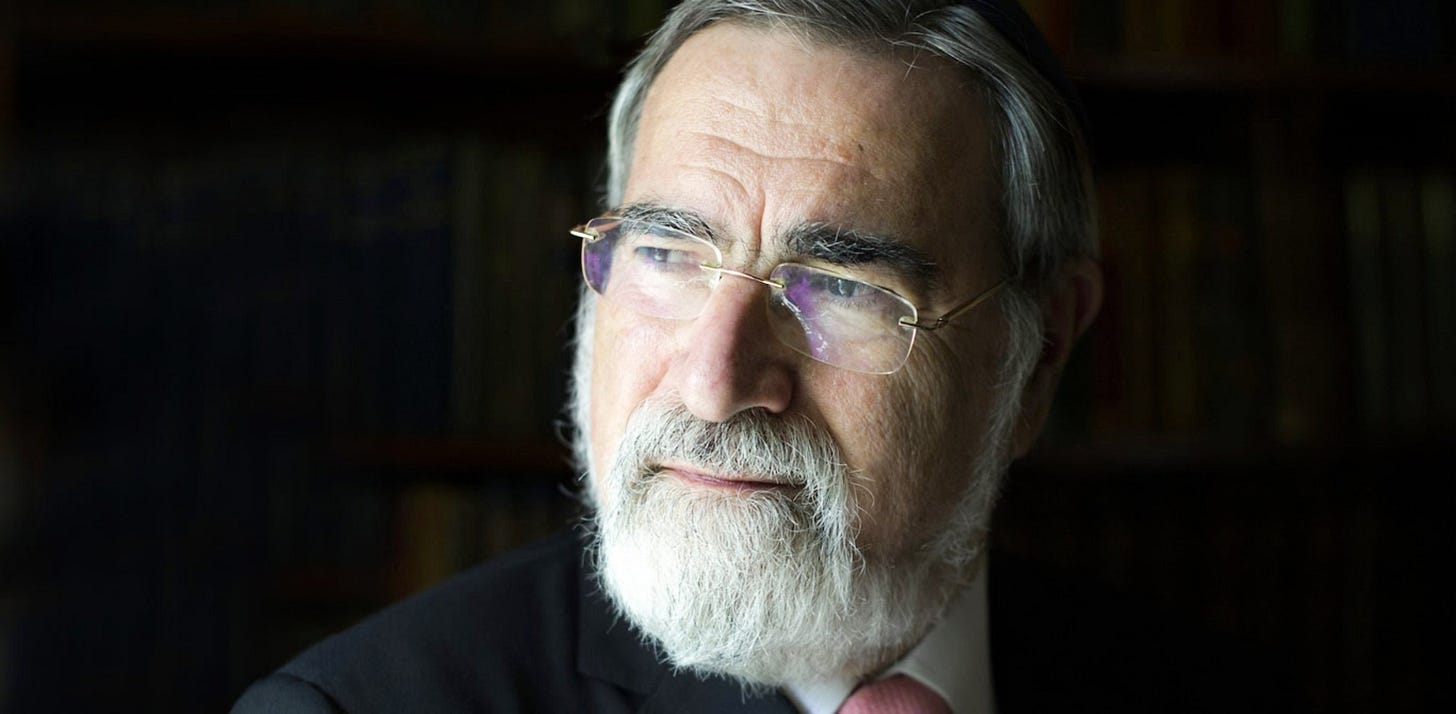

“When two propositions conflict it is not necessarily because one is true and the other is false,” the late, great Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks wrote. “It may be, and often is, that each represents a different perspective on reality.”2

The supreme challenge, according to Rabbi Sacks, is to see the goodness in one who is not in our image.

2) Don’t take anything personally.

In the age of identity politics, we tend to take everything so personally. Yet, when I asked Rabbi David Wolpe, one of the preeminent rabbis of our day, about a piece of advice he would give his younger self, he said: “Don’t take everything so personally.”

Unfortunately, it is increasingly more difficult to not take everything so personally; after all, we are living in the Age of Self: self-help, self-consciousness, self-awareness, self-actualization, self-esteem, self-development, the vaunted selfie. This is what makes Judaism so fragile today, because Judaism was never about the you’s or me’s of the day. It has always been about we, the Jewish People — past, present, and future.

Certainly, we must find our individual selves in Judaism, and I am a big believer in do-it-yourself Jewishness. But no one individual or individual group of people defines Judaism, Jewishness, and the Jewish People. They have already been defined, on a macro level, for us.

The challenge is, how do we mold ourselves, our lives, our goals and aspirations, our search for meaning and purpose, our communities and organizations, to fit these definitions? And which of these definitions can we ambitiously bend, but not destructively break? In the most Israeli way possible, of course!

“We think of ourselves as fixed and the world as malleable,” said famed entrepreneur and investor Naval Ravikant, “but it’s really we who are malleable and the world as fixed.”3

As a larger-than-life phenomenon, Judaism cannot cater to the individual. Otherwise, it would not be Judaism. It would be individual strands that have increasingly nothing to do with one another.

So I believe it is our duty, as Jews, to be malleable to Judaism, each one of us in our own ways — and each one of us respecting the others’ ways — as a sign of appreciation that Judaism was here long before us and will endure long after us.

3) Live with more chutzpah (the good kind).

The late Rabbi Harold Schulweis distinguished the meaning of chutzpah as stubbornness and contrariness from what he called a tradition of “spiritual audacity” — or in Hebrew, chutzpah klapei shmaya.

Israeli author Inbal Arieli calls it “the Chutzpah Power” — determined, courageous, and optimistic that anything can be achieved.

One of the issues amongst “fragile Jews” is that we have seemingly stopped dreaming big. We have become terrified of, intimidated by, apprehensive to, and discouraged from doing hard things. Have we frivolously forgotten that progress and success are the results of an optimistic, undying determination to try, to experiment, to get in bed with trial and error?

In the Jewish world, needle-moving progress seems to have precariously stalled. What and when was the last great Jewish innovation? I would argue, in no particular order, the Jewish world has experienced only three extraordinary, transformative gains during the last century or so:

The State of Israel (1948)

AIPAC (1963)

Jdate (1997)

Birthright Israel (1999)

This is not to say that there haven’t been other gains in the Jewish world. Of course there have been! But as Amy Sales, formerly of Brandeis University, wrote: “The difficulty for the Jewish community is to innovate without succumbing to faddism. The community regularly shifts focus from one sub-sector or enterprise to another, always in search of the next ‘big thing,’ the ‘magic bullet’ that will make Jews out of its children.”4

On a macro level, we need to reimagine a Jewish Enlightenment, or what Jewish Funders Network president and CEO Andrés Spokoiny calls creating moonshots, “to truly use the power we have to produce the changes we need. And we need to ask ourselves some hard questions: Are we willing to push ourselves to be bolder? To give more boldly? To have big, transformational dreams? Are we willing to reject the path of least resistance? To challenge conventional wisdom? In a word, are we willing to lead by example? Are we willing to create a culture that incentivizes, rather than penalizes, risk taking in ourselves and in our grantees?”5

4) Learn modern-day Hebrew.

When you think about Hebrew’s revival as the State of Israel’s official language, it really is miraculous! The language blends divinity and antiquity with the here and now, a reminder of both the surviving Jewish People and the thriving modern-day Israel.

As someone who grew up thinking Hebrew was solely for synagogue halls, I absolutely love hearing Hebrew across life’s crosshairs: on the streets of my new hometown Tel Aviv, in music and at the theatre, on TV and in movies.

But not just any Hebrew. Modern-day Hebrew. As much as we should learn the meaning of Jewish prayers, we should also be able to speak “street” Hebrew. As able as we should be to sing classic Jewish hymns like “Shalom Aleichem” and “Kol Ha’Olam Kulo,” we should also be able to create a Spotify playlist of our favorite Israeli jams. As much as we should know old-school sayings like beh’ezrat hashem, we should also know new-school slang like mah-neesh.

Hebrew is to Judaism what hands and fingers are to sign language, our story of a people scattered all over the world, while remaining a single family, a nation which time and again was doomed to destruction. Some of us returned to our homeland, others remained in the Diaspora. Some of us stayed or became religious, deeply embedded into quintessentially divine Jewish life, while others assimilated into their new countries, becoming equally “them” as they are “us.”

Is being Jewish enough to keep this family together, today and moving forward? I would argue against the affirmative, since most of us and our families have disparate, sometimes completed unconnected Jewish journeys, traditions, customs, and modes of expressing our Judaism.

Hebrew, however, can bind us together, much like it did the Jews who immigrated to Israel from Europe, the Middle East, and other parts of the world — all speaking different languages, from Polish to Persian, Arabic to English — during the years leading up to and after its 1948 declaration of statehood. Hebrew enabled complete strangers, who did not look and smell and behave like one another, to form an Israeli society now characterized by a marvelous combination of bravery, resilience, family, community, service, education, innovation, and creativity.

In today’s age of hyper-individualism, of more and more Jews describing themselves as “just Jewish” or relinquishing their Judaism altogether, and of increasing Jewish disunification, I believe we must call upon Hebrew to amalgamate us again!

“Only the Hebrew language links us to the past, present and future of the Jewish people, and to a specific land,” wrote Rabbi Mitchel Malkus. “No other language — and Jews have spoken many Jewish languages throughout our history — bonds us to the soul of our history, textual tradition, people and the land of Israel than Hebrew does.”6

“Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought.” Rabbinical Council of America.

Jorgenson, Eric. “The Almanack of Naval Ravikant: A Guide to Wealth and Happiness.” Magrathea Publishing. September 15, 2020.

“Lessons from Mapping Jewish Education.” Brandeis University.

“Being Decisive in the Face of Uncertainty (2022 Presidential Address).” Jewish Funders Network.

“The critical role Hebrew language learning plays in identity development.” eJewish Philanthropy.

I forwarded this one to my daughter, who is Head of School for Vancouver’s largest Jewish day school. You make so many points that come up in our conversations, both the things that concern us and the amazing things going on at the school about which we kvell. Kudos to you and kudos to those who support and those who provide Jewish education, including those parents who scrape together the funds to enable their children to receive it.

Raising Jewish families with dads moms children and grandchildren who are all committed to a positive view of living aJewishly committed life and who are literate in classical Jewish texts produces proud Jews .