How One Tiny Country Upended the Middle East

“Israel did not grow strong because it had an American alliance. It acquired an American alliance because it had grown strong.”

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

Israel, at least on paper, was supposed to be one of the most uninteresting places in the Middle East, no less in the world.

A six-hour drive from north to south, and no more than an hour from east to west, as Israel’s first and only female prime minister, Golda Meir, put it: Moses brought us “to the one spot in the Middle East that has no oil.”

When Jews began arriving to their indigenous homeland in the 1800s, the Galilee was swampy, the Judaean mountains were rocky, the south of the country (the Negev) was a desert, and Tel Aviv did not exist. (The area where it stands today was just a bunch of sand dunes.)

In 1867, Mark Twain visited the region and remarked it is “desolate and unlovely.” Of Jerusalem, he wrote: “… the stateliest name in history, has lost all its ancient grandeur, and is become a pauper village.”

So how did Israel go from a wasteland with a population of a few hundred-thousand people, to a country that can practically set the world on fire?

Our story could start in 1909, when some 66 Jewish families gathered on a barren sand dune in what is now Tel Aviv, to parcel out the land by lottery, a whopping total of 0.05 square kilometers (12 acres).

Akiva Aryeh Weiss, president of the building society who organized the lottery, collected 120 seashells from the Mediterranean shore, half of them white and half of them gray. The families’ names were written on the white shells and the plot numbers on the gray shells. A boy drew names from one box of shells and a girl drew plot numbers from the second box.

According to legend, the man standing behind the group, on the slope of the sand dune, is Shlomo Feingold, who opposed the idea, allegedly telling the others:

“Are you mad! There’s no water here!”

The first water well was later dug at this site, located on what is today Rothschild Boulevard, the city’s main street. Within a year, other popular streets named Herzl, Ahad Ha’am, Yehuda Halevi, Lilienblum, and Rothschild were built; a water system was installed; 66 houses were completed; and ardent Zionist Dr. Israel Kligler, a microbiologist, eradicated malaria in the region, which ironically resulted in a major share of the Arab’s population increase.

Local Arabs said that Zionists made the land “livable,” and as many as 60,000 Arabs subsequently immigrated to British-era Palestine to take advantage of new work opportunities provided by the growing population.

But in the lead-up to the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, Jewish organizations collaborated with the UN Special Committee on Palestine during the deliberations, while Palestinian Arab leadership boycotted it.

The eventual proposed plan, to which the Zionists agreed, was an international zone for the cities of Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the adjoining area, as well as 56 percent of the land allocated to the Jewish state. Much of this land included a significant portion of the Negev desert, an inhospitable environment that was worthless without major long-term investments.

Following the UN Partition Plan for Palestine, a civil war broke out and eventually led to the Israeli War of Independence, which the Jews won after fending off the armies of five Arab countries. Today the Israel Defense Forces is considered the world’s fourth-strongest military.

Back then, Zionism was inherently a Western movement — a movement that lives on the border of the East, but always faces the West. And so it is today: Israel stands against the natural tendencies of the Middle East to penetrate the West and enslave it.

“Since ancient times, in every place they have ever lived, Jews have represented the frightening prospect of freedom,” wrote novelist Dara Horn. “As long as Jews existed in any society, there was evidence that it in fact wasn’t necessary to believe what everyone else believed, that those who disagreed with their neighbors could survive and even flourish against all odds.”1

“The Jews’ continued distinctiveness, despite overwhelming pressure to become like everyone else, demonstrated their enormous effort to cultivate that freedom: devotion to law and story, deep literacy, and an absolute obsessiveness about transmitting those values between generations.”

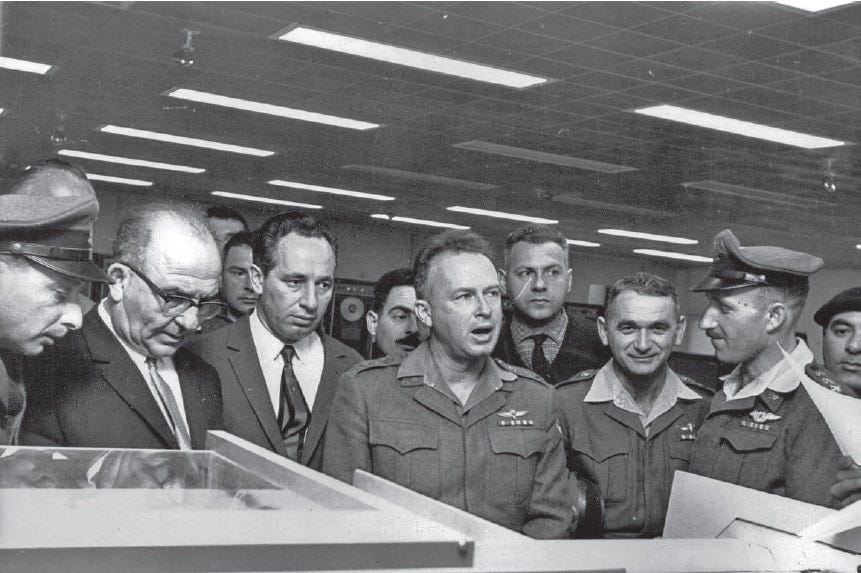

In 1952, a 29-year-old Shimon Peres was appointed deputy director general of Israel’s Ministry of Defense, and the following year, he was promoted to director general. One of Peres’ first and most significant tasks was to help engineer and implement the Sinai-Suez campaign, among the most daring and unlikely military triumphs of the post-World War II era.

It was 1956 and as the campaign unfolded, Peres had something of an epiphany. At a villa in France, where Israeli, British, and French officials had gathered to finalize planning for the campaign, Peres — then 33 years old — approached the French foreign and defense ministers and made a proposal everyone knew would be rejected out of hand.

But to everyone’s surprise (including his), the French officials agreed: France would help Israel establish its own nuclear-energy program.

Obstacle after obstacle had to be overcome, including resistance from the majority of Israel’s leadership, Soviet spying on the construction site, and serious concerns on the part of the U.S. government culminating in a tense sit-down between Peres and President John F. Kennedy.

In September 1957, Israel was set to sign an agreement with France. The French Atomic Energy Commission, after four years of negotiations, had agreed to provide Israel with a plutonium reactor. All that was needed in order to cement the deal was the signature of the French foreign minister and his prime minister.

Peres’ first stop on Monday morning, September 30th, was at the office of Pierre Guillaumat, the head of France’s Atomic Energy Commission and an avid supporter of Israel. He told Peres what he already knew: The deal could only be finalized with the French government’s approval, and their government was teetering on the edge of collapse.

Peres hurried to the office of Foreign Minister Christian Pineau, the deal’s main opponent, and Pineau promptly told Peres that he wanted to help but could not. The Americans would be livid if they found out and might impose sanctions on France, which would cripple its own dawning nuclear capacity. Moreover, the agreement could induce the Soviet Union to arm Egypt with nuclear weapons.

But Peres had come prepared. The reactor was for peaceful purposes, he said. If that ever was to change, Israel would consult with France first. Also, he said, who was to say the Soviet Union wouldn’t introduce nuclear weapons to Egypt on its own accord? Then what would the West do?

Pineau agreed, and Peres urged him to call the prime minister. Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury did not answer, so Peres convinced Pineau to dictate the terms of their agreement to his secretary. The two of them signed the paper, and then Peres convinced him that he — a foreign national — would ferry the paper to the prime minister of France.

All that was needed now was Bourgès-Maunoury’s signature. Peres went to his office and waited. The hours passed. Afternoon became evening. Several rounds of whiskey were sent to the office. And, as midnight approached, Peres had two realizations: He would not see the prime minister that evening, and the prime minister, who was stuck in parliament, was likely being defeated in a no-confidence vote.

The next morning, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary that the French government had fallen over a vote about Algeria, and that Peres’ trip to Paris was likely “for naught.”

He did not know that Peres had secured the prime minister’s oral agreement late that night and that, at nine in the morning, Peres was seated in Bourgès-Maunoury’s office. The French prime minister had not slept, and his eyes were red, for he was no longer the prime minister of France. He had no authority to sign an agreement on behalf of the Fourth Republic. But with Peres’ encouragement, he signed his consent, authorizing the agreement on a piece of paper that held the previous day’s date.

And in that way the seed of Israel’s nuclear-energy program was planted.

“This date or that, what does it matter?” Peres later said, summing up the backroom drama. “Of what significance is that between friends?”2

Israel remains the only country in the Middle East with viable nuclear weapons.

In the years leading up to and after the founding of the Jewish state, America was not a “staunch supporter” of Israel. Far from it.

During the 1800s and early 1900s, wealthy Western European Jewish philanthropists funded land purchases in Palestine by poor Eastern European Jews, who fled violent antisemitism across the Russian Empire. Most of these land purchases were done at the individual level, but there were instances when Ottoman governors themselves approved deals for Jews to buy land in Ottoman-era Palestine.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Joseph Stalin reversed his long-standing opposition to Zionism and tried to mobilize worldwide Jewish support for the Soviet war effort. In the 1950s, one of the greatest shares of Israel’s income came from German war reparations, growing to 86 percent of the Jewish state’s GDP in 1956.

Support for Zionism among American Jews was minimal, until the involvement of famous lawyer Louis Brandeis in the Federation of American Zionists, starting in 1912. And while Woodrow Wilson (the U.S. president from 1913 to 1921) was sympathetic to the plight of Jews in Europe and favorable to Zionist objectives, he did not change any U.S. State Department policies to support Zionist aims.

In 1944, two attempts by the U.S. Congress to pass resolutions declaring government support for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine were protested by the Departments of War and State, due to World War II considerations and Arab opposition to the creation of a Jewish state. The resolutions were permanently dropped.

As the end of the British mandate in Palestine approached around the mid-1940s, the decision to recognize the Jewish state remained contentious among Americans, with significant disagreement between U.S. President Harry Truman, his domestic and campaign adviser, Clark Clifford, and both the State Department and Defense Department. Rapidly changing geopolitical circumstances took place across the Middle East, and U.S. policy was generally geared toward:

Supporting Arab states’ independence

Aiding the development of oil-producing countries

Halting Soviet influence from gaining a foothold in Greece, Turkey, and Iran

Preventing an arms race in the region

All of these policies ultimately meant maintaining a neutral stance in the Arab-Israeli conflict, so much so that the U.S. put the fledgling Jewish state under an arms embargo. In the 1950s, the United States provided Israel with moderate amounts of economic aid, mostly as loans for basic foodstuffs.

It was only after Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six-Day War that America started seriously selling arms to the Israelis, who essentially proved their value as an ally by virtue of this victory.

“Israel did not grow strong because it had an American alliance,” according to Walter Russell Mead, a professor at Bard College. “It acquired an American alliance because it had grown strong.”3

In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against Israel on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur. Israel wanted to preemptively attack, but U.S. leadership warned Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir against initiating a war in the Middle East.

According to U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, had Israel struck first, it would not have received “so much as a nail.” The Israelis did not want to jeopardize U.S. military resupply and got off to a terrible start in the war, which came as a surprise following their extraordinary victory in the Six-Day War just six years earlier.

Three days into the war, it became painstakingly clear that no quick reversal in Israel’s favor would occur, and that military losses were unexpectedly high. An alarmed minister of defense, Moshe Dayan, told Meir that “this is the end of the third temple” — a reference to the two previous Jewish sovereign periods which ended poorly for the Jews.

Sure, Dayan was warning Meir of the potential for a total defeat, but “Temple” was also the code word for Israel’s nuclear weapons. After discussing the nuclear topic in a cabinet meeting, Meir authorized the assembly of 13 tactical nukes to be used if absolutely necessary.

However, it was done in an easily detectable way, likely a signal to U.S. leadership. Kissinger quickly learned of the nuclear alert and, on the same day, U.S. President Richard Nixon ordered the commencement of Operation Nickel Grass, an American airlift to replace all of Israel’s material losses. As a result, Israel ended up defeating both Egypt and Syria, which completely upended the Middle East, but in a totally unforeseen way.

Following Israel’s victory in the Yom Kippur War, the OPEC oil cartel — led by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia — decided to embargo many of Israel’s supporters, including the U.S. for resupplying the Israelis (and to gain leverage in post-war negotiations).

The embargo caused the global price of oil to quadruple from $3 to nearly $12 per barrel. Over the following decade, the deluge of money that flowed into Saudi Arabia made it one of world’s wealthiest countries, and the House of Saud one of the world’s wealthiest families.

With their newfound wealth, the Saudi royal family made its great bargain with the Saudi people, especially with the state’s minority groups which did not exactly appreciate the Sunni Muslim laws.

The unworldly revenues that the state was earning from its oil enabled the kingdom to basically bribe its citizens, especially the country’s Shi’ite Muslims, who were a minority compared to the Sunni Muslims, but who lived in areas where the vast majority of oil fields were found.

In other words, Saudi Arabia became a massive welfare state: Zero taxes were levied on anything or anyone. Oil paid for all of the government’s budget, including healthcare, education, food, water, fuel, and electricity.

In exchange, the kingdom expected that citizens would accept some of the strictest and most totalitarian religious laws across the world. And, more importantly, that citizens would accept the House of Saud’s absolute legitimacy to rule a medieval kingdom in a 20th-century world. Naturally, this created domestic stability — for the first time in a long time — and dramatically reduced the chance of outsiders successfully overthrowing the kingdom.

In 1976, Iraq purchased an Osiris-class nuclear reactor from France.

While Iraq and France maintained that the reactor, located 17 kilometers (11 miles) southeast of Baghdad, was intended for peaceful scientific research, the Israelis viewed the reactor with suspicion, believing it was designed to produce nuclear weapons that could escalate the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict.

In June 1981, the Israeli Air Force launched Operation Opera: an airstrike that destroyed the reactor. It was met with sharp international criticism, including in the United States, and Israel was rebuked by the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly in two separate resolutions.

Media reactions were also negative. “Israel’s sneak attack ... was an act of inexcusable and short-sighted aggression,” wrote The New York Times, while the Los Angeles Times called it “state-sponsored terrorism.”

Meanwhile, the destruction of Iraq’s nuclear reactor has been cited as an example of a preventive strike in contemporary scholarship on international law. It also established the Begin Doctrine — named after then Israeli prime minister, Menachem Begin — which explicitly stated the strike was not an anomaly, but instead “a precedent for every future government in Israel.”

During the 1990s, a wave of immigrants from the former Soviet Union arrived in Israel. Tel Aviv absorbed more than 40,000 of them, many educated in scientific, technological, medical, and mathematical fields. During this period, the number of engineers in the city doubled, and Tel Aviv began to emerge as a global hi-tech center.

But in 1998, Tel Aviv was on the “verge of bankruptcy,” according to its current mayor, Ron Huldai. Economic difficulties were then compounded by a wave of Palestinian suicide bombings across the city from the mid-1990s to the end of the Second Intifada in 2005, as well as the dot-com bubble, which affected the city’s rapidly growing hi-tech sector.

After the 2003 Israeli legislative election, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon offered the Finance Ministry to Benjamin Netanyahu, in what many observers regarded as a surprise move. Some pundits speculated that Sharon made the move because, given Netanyahu’s demonstrated effectiveness previously as Foreign Minister, Sharon deemed him a political threat; by placing him in the Finance Ministry during a time of economic uncertainty, Sharon could theoretically diminish Netanyahu’s popularity.

As Finance Minister, Netanyahu adopted a liberalized economic plan in order to restore Israel’s economy from its low point during the Second Intifada. His strategy involved reducing the size of the public sector, freezing government spending, capping the budget deficit at one percent, attacking monopolies and cartels to increase competition, streamlining the taxation system and cutting taxes, privatizing a host of state assets, and raising the retirement age.

As the Israeli economy started booming and unemployment significantly fell, Netanyahu was widely credited by commentators as having performed an “economic miracle” by the end of his tenure.

Today, across the Middle East, Israel has the second-highest compound annual growth rate, the third-highest share of global GDP growth, and the highest life expectancy.4

In addition, the Jewish state boasts the world’s most (per capita) engineers and scientists, startups expenditure on research and development as a percentage of GDP, and most hi-tech “unicorns,” as well as the second-most venture capital investments and third-most university degrees.

Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first president and one of the greatest Zionist leaders and visionaries, was once asked by a Lord in the British Parliament, before the Jewish state was founded, “Why Palestine? Why not try elsewhere, somewhere you would have less enemies, less struggles, less hardships and difficulties, somewhere closer perhaps?”

Weizmann replied:

“My dear Lord, why is it that you insist on driving two-and-half hours — every weekend — to visit your elderly mother, when there is a perfectly decent nice old lady living just across the street?”

“Why the Most Educated People in America Fall for Anti-Semitic Lies.” The Atlantic.

“A back-dated deal with a toppled French PM: How Peres secured Israel’s nuclear deterrent.” The Times of Israel.

Mead, Walter Russell. “The Arc of a Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People.”

“Middle East.” World Economics.

It might be more precise to say, rather than "a civil war broke out" following the adoption of the Partition Plan, that the Arabs launched a civil war. Jamal Husseini, the brother of the Nazi Mufti, openly admitted that the Arabs initiated the fighting. See UN Security Council meeting 283, page 19 (the PDF of the meeting minutes can be accessed here: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/635417?ln=en#record-files-collapse-header).

Excellent. This should be required reading on every American university campus.