In the UK, Jew-hatred is hijacking education.

As anti-Israel activism intensifies within Britain’s largest teaching union, Jewish teachers describe a culture of intimidation, historical distortion, and political indoctrination.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay by Nicole Lampert, a journalist and commentator.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

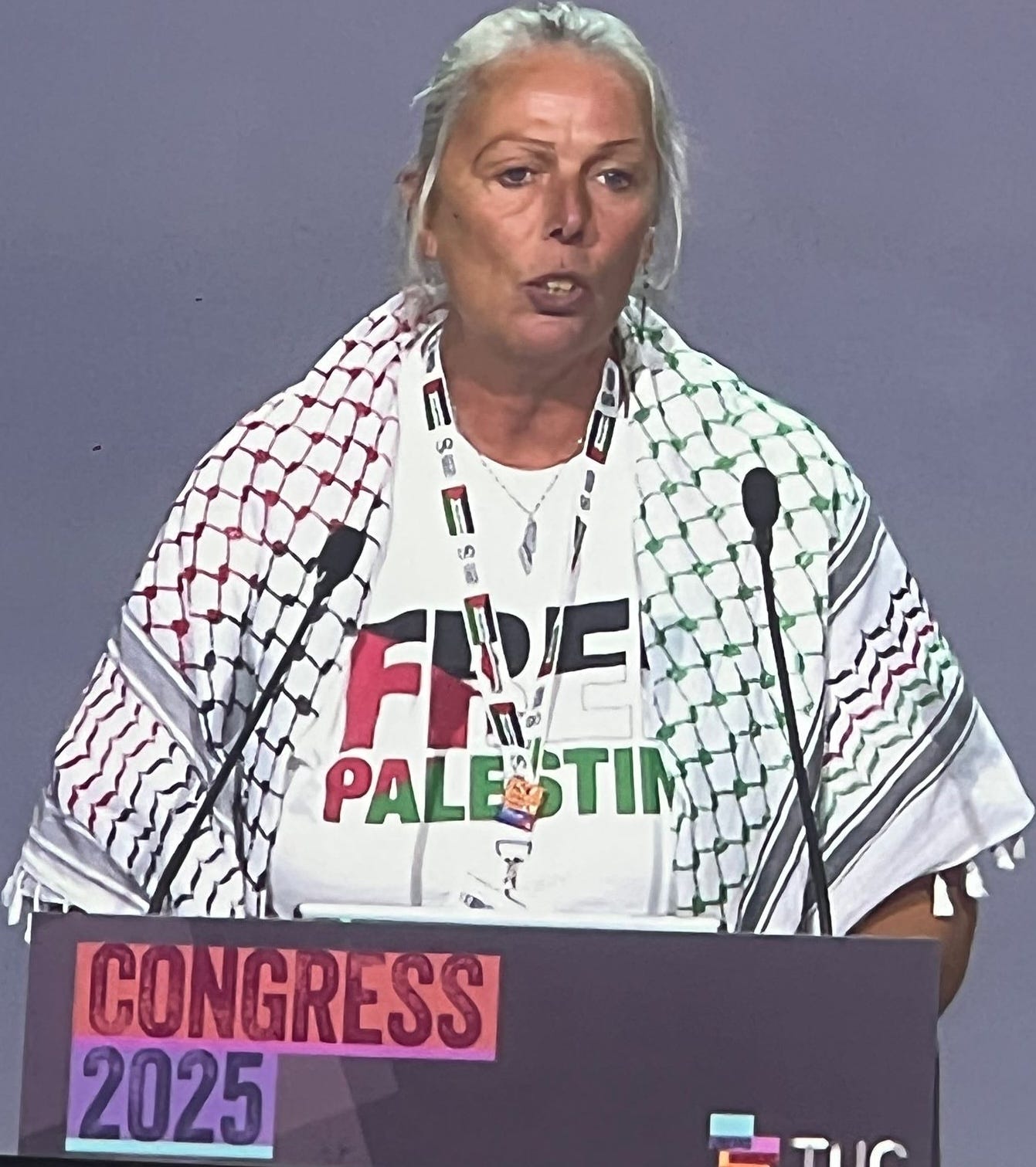

Daniel Kebede is the General Secretary of the UK’s largest teaching union, the National Education Union.

Last year, he was photographed at an anti-Israel rally with Louise Regan, an executive committee member for the union who also serves as chair of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign. In 2021, Kebede stood at another anti-Israel demonstration and called to “globalise the intifada.”

A year ago, when I first wrote about the National Education Union’s anti-Israel obsession — and how it was seeping into classrooms — it was circulated to Labour Party ministers. It was ignored.

Then, last month, at the Jewish Labour Movement conference, Communities Minister Steve Reed attempted to explain how he understood that antisemitism was wrong because a colleague and friend of his had been banned from visiting a school in his own district. He did not seem to realise how shocking that admission would sound to many of us. Following my original article, I was asked to write a series of further deep dives into what is unfolding in our schools.

Fortunately for me as a journalist — though far less fortunately for me as a Jewish person confronted with the full horror of anti-Israel propaganda — examples were not difficult to find.

For The Telegraph, I spoke to two Jewish National Education Union members. One revealed that the union representative at her school had calmly informed her that Israel did not exist. The other described the emotional toll of the union’s relentless Israel obsession, recounting how teachers proudly showcased their pro-Palestine classroom activities.

For the Daily Mail, I examined the classroom impact: historical distortions and outright falsehoods designed to erase the Jewish story. In the Jewish Chronicle, I helped expose how, just days after the October 7th massacre, the Bristol branch of the National Education Union — which had previously celebrated preventing Jewish Member of Parliament Damien Egan from visiting one of their schools — circulated teaching materials inviting pupils to sympathise with Hamas’ actions.

In another piece for The Telegraph, I revealed how even Holocaust Memorial Day is now being weaponised against Jews, as claims of a “Gaza genocide” are promoted by both pupils and teachers.

The shadow education minister has since called for an investigation into the National Education Union. Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson has said she will look into the matter — which, in journalism, feels like a small but meaningful victory.

This could not be more important. For years, we have witnessed rising hostility toward Jews on university campuses. Now that same atmosphere is being replicated in schools. And yet this has been developing for a long time. I worry that the political will to confront it simply is not there.

The following accounts come from two National Education Union members who requested anonymity.

Louise, a special needs assistant at a school in North London, told me that the moment she truly began to question the National Education Union — a union she had belonged to for nearly a decade — was when the representative at her own school calmly informed her that Israel did not exist. She had never attended branch meetings or conferences; she knew the union leaned Left, but she had not grasped just how far things had shifted.

Shortly after October 7th, upset and worried because she has family in Israel, she went to speak to the National Education Union rep in her office. They were friends. At first the rep was sympathetic. Then, without hesitation, she stated that Israel did not exist. When Louise asked what she meant, the rep explained that she had been shown maps at a union meeting and that the land was Palestine, not Israel. Louise stressed to me that this was not a fringe figure but an intelligent woman. She was left stunned into silence. In the days that followed, she sent articles and videos outlining Israel’s history. She never received a response. She told me she wished she had replied more forcefully — that she travels to Israel almost every year, so of course it exists — but in that moment she did not dare.

What disturbed her further was the realisation that this kind of denialism was not isolated. One afternoon at lunch, while colleagues were eating falafel, the conversation turned into a discussion about it being a Palestinian dish and quickly expanded into broader commentary about Palestine. In the playground, she overheard two teachers discussing the “genocide” in Palestine in front of pupils. She reported it to the headteacher.

The head soon imposed a ban on discussing the conflict on school grounds. Louise described this as a double-edged solution. On the one hand, it curbed overt political talk. On the other, she works in a predominantly Muslim area where, in her view, only one narrative continues to circulate — and it feels as though challenging that narrative is effectively off limits.

Her family history shapes how she sees all of this. Both of her parents were Hungarian. Her father’s family perished in the Holocaust; he survived only because he had already been working in the UK. Her mother fled communist Hungary in 1956. Louise told me she understands antisemitism and she understands what compelled, ideological speech looks like under authoritarian systems. Teachers, she believes, should not be engaged in indoctrinating children. She should not have to tiptoe around a subject that directly touches her own identity. To her, it feels like dangerously unstable ground.

She described National Education Union WhatsApp groups as saturated with Palestine, relentlessly advancing the idea that Israel is not a legitimate country. It felt to her almost pathological — a post-truth insistence on Israel’s non-existence. Though she did not attend meetings herself, she saw that the union president had publicly called to “globalise the intifada.” In her view, someone who uses that language should not be leading a teaching union.

The breaking point came when she saw online that the union conference had announced that hundreds of thousands of pounds from members’ subscriptions would be sent to organisations in Palestine. There was no clarity, she said, about which organisations would receive the money or what due diligence had been conducted. That was not what she believed she had signed up for.

All of this has led her to question whether she even wants to remain in the UK. Before the war, she had never contemplated moving to Israel. Now she has begun the paperwork. Her 30-year-old daughter may follow.

At its core, Louise believes education should be about truth — including acknowledging that Israel is a legally established state. If teachers are siding with terrorists and indoctrinating children, she fears the country is entering profoundly dangerous territory, not only for Jews but for everyone. Most of all, she no longer wants to conceal her Jewish identity or her support for Israel. Increasingly, she feels she lives in a country where only certain voices are permitted to speak.

Sarah is another teacher in East London. She told me that just two weeks after the October 7th attack — in which members of her own family were killed and taken hostage — her union released a statement declaring that Palestinians had the right “to resist Israeli settler colonialism by all available means including armed struggle.” She described feeling horrified and furious, and found herself wondering what a war 2,000 miles away had to do with a British education union.

She explained that the union had long shown interest in Palestine. She remembered the 2021 conflict between Israel and Hamas prompting motions and demonstrations within the National Education Union. But in her view, after October 7th what had once been a fringe preoccupation became mainstream.

Looking back over two years of National Education Union WhatsApp messages, she said the pattern was unmistakable — a constant drumbeat of “Palestine, Palestine, Palestine.” The union magazine, she observed, appeared to revolve around a single theme. While many teachers pay little attention to union politics, she said there is a cohort that is deeply engaged. The most politically active attend branch meetings dominated by discussions about Palestine, then carry that activism back into their schools, at times feeding it directly into lessons.

On local group chats, during union “days of action” for Palestine, she has seen teachers post photographs of themselves holding Palestinian flags in front of their pupils. They share suggestions about weaving Palestine into the curriculum, encouraging children to colour Palestinian flags and even chant “intifada revolution.” She told me she had seen reading materials recommending that pupils watch Al Jazeera, a broadcaster funded by a state that sponsors Hamas.

What astonishes her, she said, is that the union appears to be encouraging teachers to blur, if not breach, educational neutrality. Union representatives, aware of the additional protections attached to their roles, are often at the forefront of this activism, influencing colleagues and, in some cases, radicalising students.

Even now, she pointed out, despite the war having ended, the union is hosting yet another “how to educate about Palestine” day in July. The focus, she said, is relentless.

At the same time, she acknowledged that the union has supported her in the past, and that every teacher at her school belongs to the National Education Union. Leaving would leave her isolated within her workplace. So although she feels alone within the union’s culture, remaining means she is not professionally alone at school.

She described how some teachers wear Palestinian badges. In her view, politics does not belong in the classroom. Several stopped wearing them only after the headteacher asked whether they would be prepared to present both sides fairly if questioned by pupils. Even so, she finds their presence isolating. She avoids political conversations entirely. The war and its aftermath have been emotionally exhausting for her; she now largely steers clear of social media and focuses simply on doing her job as well as she can.

She told me that many Jewish teachers have already left the National Education Union, and she does not blame them. In her view, it has become a hostile environment for Jews. The singular fury directed at the one Jewish state feels to her like antisemitism, even when it is framed as compassion.

She spoke of what she sees as a troubling convergence: longstanding antisemitism imported from certain cultural contexts merging with far-left antisemitism. The union, she believes, refuses to acknowledge this dynamic. She was not surprised that the National Education Union was involved in efforts to block Damien Egan from visiting a school. In what she considers a functioning democracy, she asked, how can an elected representative of a mainstream party be deemed unsafe to step inside a school?

The union also campaigns against Prevent (a UK government programme aimed at stopping people from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism by providing early, voluntary intervention and support), describing the anti-radicalisation programme as racist. Yet she argued that some teachers who are ideologically indoctrinating children would, in her view, warrant scrutiny under anti-radicalisation frameworks.

She avoids branch meetings because she does not want to see the full scale of what is happening. But by remaining in the union, she feels she preserves at least a small Jewish presence within it. When Daniel Kebede is challenged about the union’s fixation on Palestine, she noted, he calls it “democracy.” Yet she admitted she would be afraid to tell colleagues that she has family in Israel. That, she said, is how intimidating the environment has become. And if Jews feel they must leave in order to feel safe, she believes it can no longer meaningfully be called a democracy.

Leah is already in conflict with fellow pupils and teachers over this year’s Holocaust Memorial Day assembly.

At her Manchester private school, the Jewish Society and Humanitarian Society is tasked with writing the assembly together. Last year, students attempted to insert references to a “Gaza genocide,” while a teacher proposed adding a paragraph about the war in Gaza, citing concerns about “anti-Muslim hatred.”

Leah and another Jewish pupil insisted that Holocaust Memorial Day focus on the Holocaust. This year, the same struggle has resurfaced. “A pupil wanted to include a paragraph about the ‘recognised genocides in the Middle East and Sudan in the last 12 months,’” she explained. “It reflects what’s happening more broadly. I’ve overheard people say about a younger pupil, ‘I wouldn’t be friends with her because she supports Israel.’ I report incidents, but nothing seems to change. Now we’re fighting again to have that paragraph removed before the assembly.”

At least her school is still marking the day. Since the October 7th Hamas massacre in 2023, the number of schools commemorating Holocaust Memorial Day has more than halved. According to the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, approximately 2,000 secondary schools marked Holocaust Memorial Day in 2023. That fell to 1,200 in 2024 and to just 854 last year.

“There are cancellations driven by good faith and others by bad faith,” said Holocaust Memorial Day Trust chief executive Olivia Marks-Woldman. Some teachers feel ill-equipped to manage attempts to introduce unrelated contemporary conflicts. Others seek to use Holocaust Memorial Day to advance political agendas. “We have received letters saying schools would only participate if we issued statements condemning Netanyahu,” she said. “Commemorating the Holocaust should not be conditional.”

The Islamic Human Rights Commission, a pro-Iran group that helps organise London’s annual anti-Israel Quds Day march, urged 460 councils and universities to boycott Holocaust Memorial Day events unless Gaza was included among the genocides recognised.

Survivor Mala Tribich, who endured Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen, has noticed declining engagement from schools. “You would be surprised how many adults know nothing about the Holocaust,” she said.

Some schools, like that of Hannah, a Jewish parent in South London, have quietly dropped the commemoration altogether since October 7th, citing other programming priorities. And even where Holocaust Memorial Day continues, tensions persist. Jo, a librarian from North London, describes colleagues attempting to insert Gaza into her exhibition. “It felt like an effort to erase Jewish centrality to Holocaust Memorial Day — to transform Jewish victimhood into Jewish guilt,” she said.

There are tentative signs of renewed interest following the Manchester synagogue terror attack and a fragile ceasefire in Gaza. Holocaust education charities report increased bookings. But the broader question remains: how can antisemitism be rising when Holocaust education is mandatory?

Part of the answer may lie in how it is taught. For Jael Cohen-Rothschild, 21, Holocaust education consisted primarily of watching “The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas” — a story widely criticised by educators for centring empathy on the son of a Nazi commandant rather than Jewish victims. “There was no proper contextual teaching,” she said. “No explanation of how six million Jews were murdered.”

Historian Simon Sebag Montefiore recently warned that the Holocaust is increasingly being weaponised against Jews. Speaking at the Holocaust Education Trust in Westminster, he described how the Soviet Union began labelling Israel’s wars as “genocide” as early as 1969 — an inversion that has resurfaced with force.

“The brazen killing of October 7th,” he said, “unleashed the latent Holocaust inversion trope against Israel and Jews globally.” The moral authority of the Holocaust, once central to defining genocide as the ultimate evil, is now being invoked to justify boycotts and even violence against Jews.

The memory of six million murdered Jews is being commandeered in service of a narrative that turns history on its head. And in our schools, that inversion is no longer theoretical. It is being taught.

The UK, perhaps more than any other European country, echoes Germany of the 1930s. In addition to the corruption of the educational system, the NHS also is a hotbed of antisemitism. In Brighton, the Jew haters are going door-to-door asking if people will boycott Israeli products and keeping a list of those who say no. The two tier policing system and the exclusion of Israelis by the Manchester police is well-documented. It is evident that Starmer will do nothing to curb the UK’s downward antisemitic spiral, and many Labour MPs are dependent on Muslim votes to maintain power. This is my question for Ms. Lampert: Do Jews have a future in the UK?

More proof that antizionism is the “new” Nazism.