The Saudis need Israel more than Israel needs the Saudis.

Forget the Abraham Accords. Israel is the only actor the entire region quietly fears and respects.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Many people are up in arms following U.S. President Donald Trump’s announcement this week that he would sell F-35 warplanes to Saudi Arabia.

But the real story isn’t the sale itself; it’s how we got here, and what it reveals about power, perception, and the realities of the Middle East.

In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. Israel wanted to strike first, but U.S. leadership warned Prime Minister Golda Meir against preemptive action.

According to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, had Israel acted unilaterally, it would not have received “so much as a nail” in military support. Israel, mindful of U.S. resupply, entered the war at a disadvantage, despite the stunning victory it had achieved just six years earlier in the Six-Day War.

Three days into the conflict, as losses mounted, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan warned Meir: “This is the end of the Third Temple.” While he was signaling potential military disaster, “Temple” was also the code for Israel’s nuclear arsenal. Meir authorized the assembly of tactical nukes in a deliberately detectable way — a signal to the United States. Kissinger quickly learned of the alert, and on the same day President Richard Nixon ordered Operation Nickel Grass: a massive airlift to replenish Israel’s losses.

The result? Israel defeated Egypt and Syria decisively, reshaping the Middle East in a way few predicted.

The aftermath of the war rippled far beyond Israel. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), then led by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, embargoed oil exports to Israel’s allies, including the United States, attempting to leverage the post-war negotiations. (Ironically, it was the U.S. that had helped the Saudis unlock their oil wealth decades earlier.)

The embargo caused the global price of oil to quadruple from $3 to nearly $12 per barrel. Over the following decade, the deluge of money that flowed into Saudi Arabia made it one of world’s wealthiest countries, and the House of Saud one of the world’s wealthiest families. With their newfound wealth, the Saudi royal family made its great bargain with the Saudi people, especially with the state’s minority groups which didn’t exactly appreciate the Sunni Muslim laws.

The unworldly revenues that the state was earning from its oil enabled the kingdom to basically bribe its citizens, especially the country’s Shi’ite Muslims, who were a minority compared to the Sunni Muslims, but who lived in areas where the vast majority of oil fields were found. In other words, Saudi Arabia became a massive welfare state: Zero taxes were levied on anything or anyone. Oil paid for all of the government’s budget, including healthcare, education, food, water, fuel, electricity and, apparently, F-35s.

Yet, even with all that money, owning F-35s does not automatically equate to knowing how to use them. When Trump sold F-35s to Turkey recently, an IDF source called it “a headache” — annoying, yes, but entirely manageable. Israel’s advantage isn’t in the size of its arsenal; it’s in mastery. Intelligence, reconnaissance, modeling, simulation, strategy, and logistics — these are the tools that allow Israel to turn small numbers into decisive outcomes. You can hand anyone a supercomputer, but that doesn’t mean they know what to do with it.

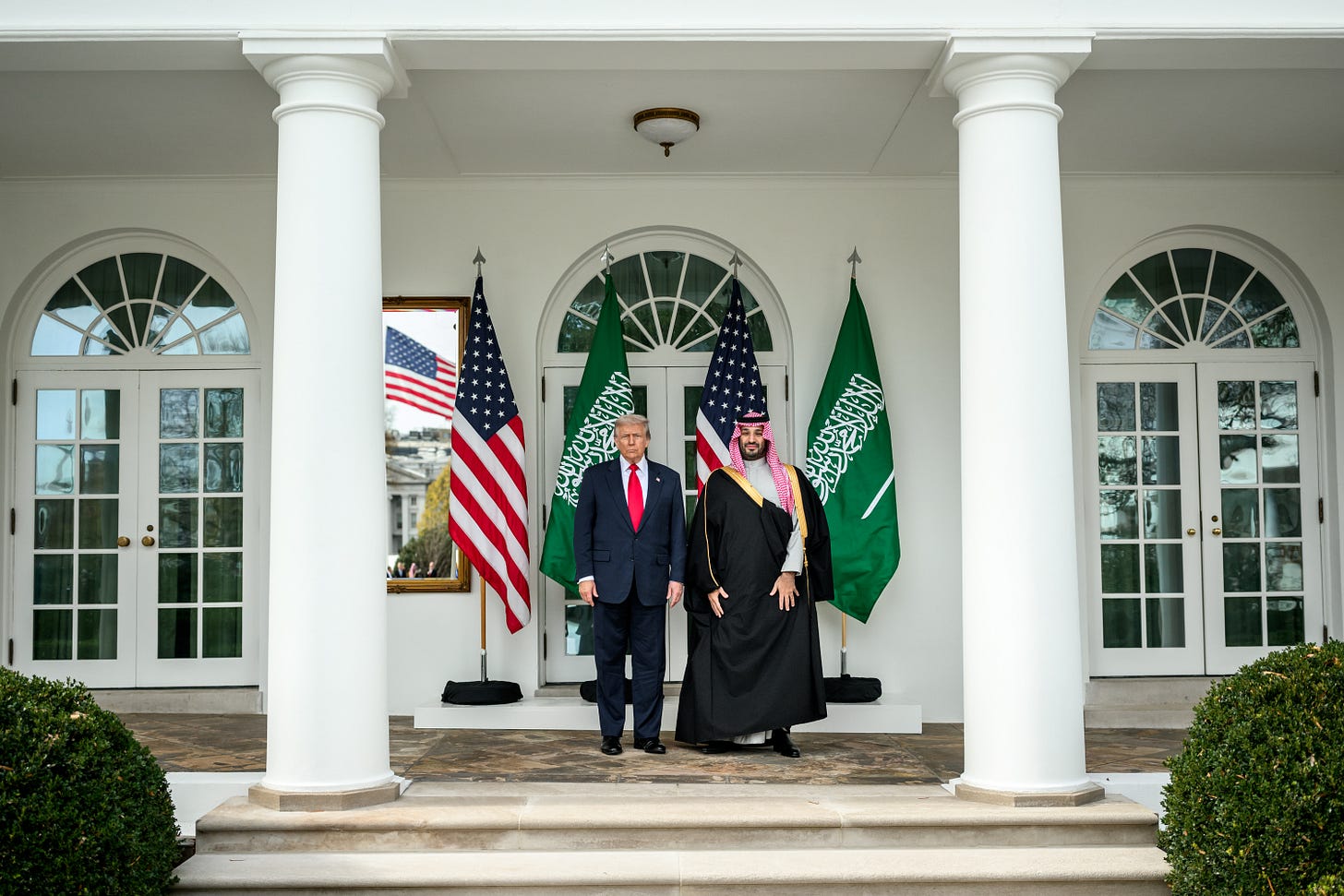

Also this week, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman told President Trump at the White House that Riyadh wants to join the Abraham Accords, but insisted on the need to “secure a path toward a two-state solution” between Israel and the Palestinians, an essentially empty statement. Publicly invoking the outdated “two-state solution” allows the crown prince to appease domestic and regional audiences while maintaining the very real, practical alliance that benefits Riyadh’s security and geopolitical interests. In other words, it’s diplomacy for show, not for substance.

And the idea that Israel somehow needs Saudi recognition is laughable. The Saudis have recognized Israel for decades — not publicly, but quietly, pragmatically, and consistently.

During Operation Opera in 1981, for example, Israel struck Iraq’s French-built nuclear reactor, reportedly with Saudi cooperation, since the flight path crossed their airspace. Countless other forms of covert coordination have followed, including during the recent two-year proxy war with Iran. The truth is simple: Saudi Arabia needs Israel far more than Israel needs Saudi Arabia. To pretend otherwise is to confuse theater for reality.

Consider the contrast: Saudi Arabia may have wealth, size, and manpower, but it lacks operational mastery. It lacks the integration of intelligence, logistics, strategy, and innovation that makes Israel so formidable. It lacks the ability to turn limited resources into decisive advantage. Israel thrives because it knows how to fight smarter, act faster, and adapt relentlessly. It survives because it turns necessity into opportunity, scarcity into innovation, and danger into strategic clarity.

Publicly, the Arabs project strength — mainly for domestic audiences, because weakness invites internal instability. Privately, they recognize Israel’s mastery, adjusting their behavior accordingly and fearing the Israelis: their intelligence, their precision, their technological edge, and their ability to turn limited resources into decisive power. That quiet respect, bordering on apprehension, drives much of the region’s covert diplomacy and unspoken calculations.

Of course, Israel’s qualitative edge extends beyond weapons. It’s cyber capabilities, elite special forces, missile defense systems, and a research and development ecosystem that turns innovation into battlefield advantage faster than any adversary can respond.

And looming behind all of this is a reality every Arab regime understands, even if they’ll never admit it publicly: The Mossad knows everything. For decades, Israeli intelligence has penetrated Arab governments, militaries, security services, and proxy networks with a level of precision that terrifies regional governments far more than any F‑35 ever could. From assassinations in the heart of Damascus, to extracting a half‑ton of Iran’s nuclear archive from a guarded warehouse in Tehran, to revealing plots long before they materialize, the Mossad has built a reputation for omnipresence.

Arab leaders know that Israel’s intelligence services can map their power structures, identify their fault lines, monitor their internal stability, and in many cases, predict their moves before they make them. This isn’t speculation; it’s the starting assumption of every serious Arab strategist. And because they know Israel knows, it shapes their behavior. It restrains their ambitions. It narrows their options. It forces them to think twice, thrice, and then again before crossing certain red lines.

For regimes built on fragile coalitions, tribal loyalties, and decades‑old patronage networks, the thought that an external actor understands their internal dynamics better than their own intelligence apparatus is not just humiliating; it’s existential. That quiet dread is one of Israel’s most potent deterrents.

And so, as headlines flash about jets, arms deals, and diplomatic posturing, one truth remains clear: Israel’s survival and dominance have never depended on Saudi recognition or the quantity of weapons its neighbors possess. It depends on skill, resilience, and an unmatched ability to turn challenges into advantages.

That is why, quietly or openly, the region fears Israel — and why anyone who bets against it is almost always reminded, in short order, that the Israelis, for all their internal chaos, summon a clarity and competence in moments of crisis that turn predictions of their decline into yet another footnote in a long history of miscalculations.

And Israel’s true strategic power doesn’t rest solely on conventional weapons. Though officially undeclared, Israel possesses a credible nuclear arsenal, long recognized as a deterrent that shapes regional calculations. This capability isn’t about flaunting missiles; it’s about ensuring that no adversary (whether state or proxy) can credibly threaten its survival.

From the Yom Kippur War to today, the mere knowledge that Israel has nuclear weapons has influenced U.S. support, regional diplomacy, and the caution exercised by neighboring powers. It’s a silent, omnipresent force multiplier — an insurance policy that reinforces Israel’s qualitative edge while remaining deliberately opaque.

The lesson for anyone observing the F-35 sale, for anyone parsing headlines, or for anyone trying to make sense of Middle East geopolitics is simple: Saudi Arabia doesn’t want F-35s to use against Israel. Riyadh knows exactly what every serious military strategist knows: Israel isn’t the threat. Israel is the region’s stabilizer, the one player that has zero interest in toppling the House of Saud.

The F-35s are about something else entirely: Iran, the Islamist bully of the neighborhood. The regime that arms proxies on every border, blows up oil facilities, threatens shipping lanes, and dreams openly about regional hegemony. The Saudis want American jets not because they fear Jerusalem, but because they need a buffer against Tehran — and they know that if the Iranians ever pushed too far, Israel would be the only country in the region actually capable of stopping them.

Most important thing I draw from this is that Israel must be self-sufficient in producing its own weaponry. I never knew that Israel wanted to strike first before the Yom Kippur war broke out. The US, because of Israel's reliance on American weapon supply, was able to stop her. Same problem we had with Biden and other Presidents. No more. We need to be as independent as possible. Thank you for a great read through our history!

Excellent history lesson. At the same time that you explain Israel's strengths and express an optimism that we must hold on to, I see and hear that we must continue to work hard and innovate. We must somehow work, innovate, and pray to overcome the strategic disadvantages that are inherent in The Land of Israel and plague Bnei Yisrael.

From another source: before enlightenment we chop wood and carry water and after enlightenment we chop wood and carry water. And, as H' said to Yaakov, This World is for work. You can rest in the Next World. We can gather energy from our accomplishments and we can continue forward to new accomplishments.