Learning to Love the Lessons of Jew-Hatred

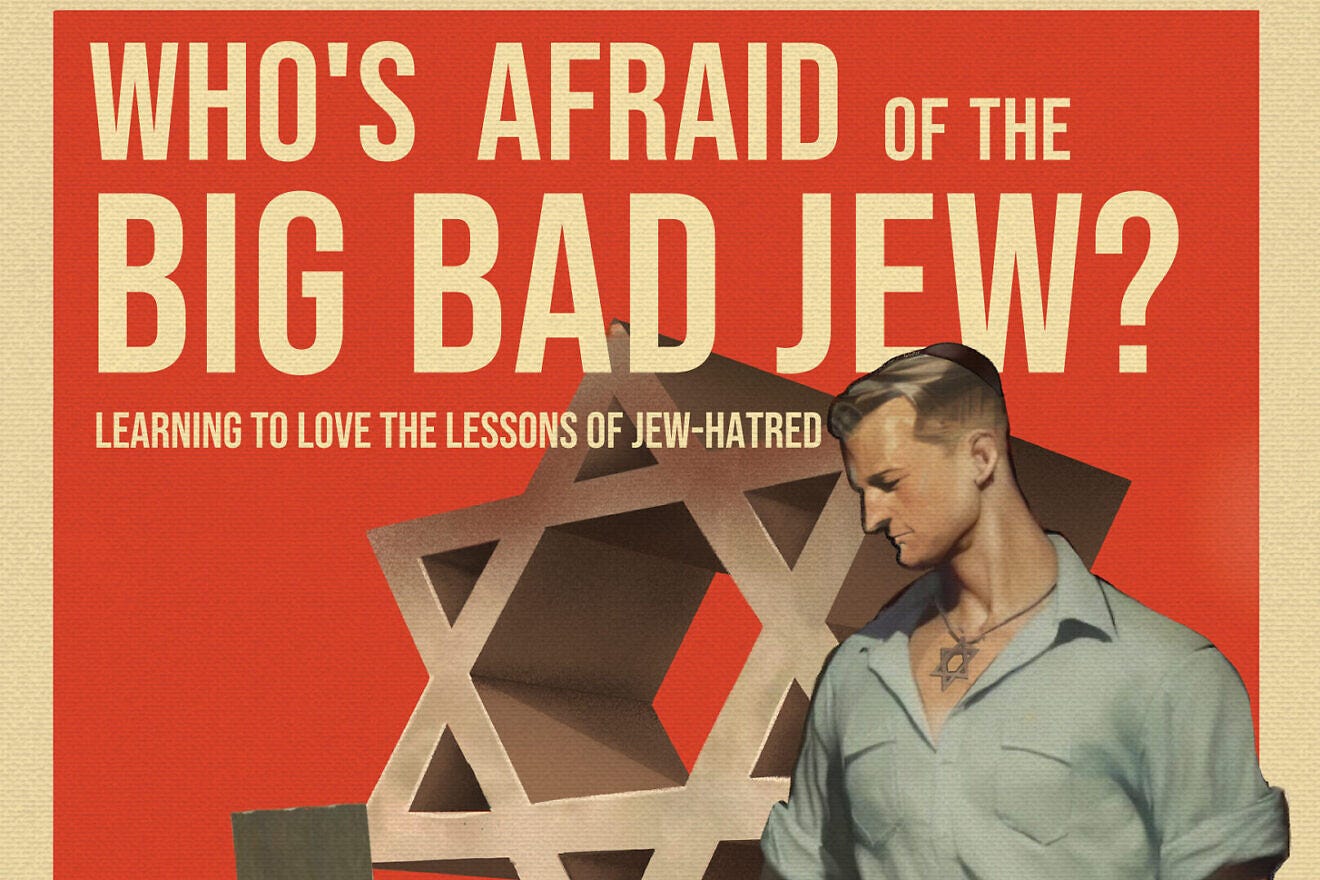

Enjoy this excerpt from my new book, “Who's Afraid of the Big, Bad Jew.”

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is an edited excerpt from the new book, “Who's Afraid of the Big, Bad Jew: Learning to Love the Lessons of Jew-Hatred” — written by Raphael Shore, an acclaimed filmmaker and author.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

No Jews Allowed.

That was the sign my high school friends hung on the door of our usual weekend haunt.

How blissfully ignorant had I been?

As I was growing up, I never cared much, or thought about, my Jewishness.

I was not one to search for answers to life’s mysteries (not even the obvious things) — I was more of the partying type. Perhaps I was even heading out the door of Judaism (or the Jewish People). Growing up happily in the small town of London, Ontario, Canada, among the northern snows, I gave little thought to things like that.

A lousy Hebrew school education at my family’s conservative synagogue had convinced me that there was no compelling meaning to my Jewish identity, just some empty rituals and silly “Bible stories.”

But the wake-up call came on that fateful Friday night in 1978, when my long-standing “friends” locked the doors to the routine weekend party and told me, my brother, and our other Jewish friend, Stewart, that we were not welcome. I was shocked to the core (and it was then that I got into my first and only fist fight).

Stewart had regularly suggested to me that many of our “friends” harbored antisemitic feelings (maybe that is why the hockey jock guy laughed at me when he broke my finger playing soccer?), but I had always disagreed with him. Until then. Antisemitism was real. But what was there about us to hate? I was just like everyone else. Why would anyone hate me over a religion I did not practice or know anything about?

This startling reality that hit me at age 17 was experienced by Jews around the world recently when Hamas committed its cruel massacre of 1,200 Jews on October 7th, 2023. The vicious attack, which included indiscriminate killing and raping, shocked people the world over.

Equally horrifying was the post–October 7th explosion of hatred toward Jews and Israel. It was a wake-up call for Jews in Israel and around the world who thought that maybe antisemitism had died with the 6 million slaughtered in the Holocaust.

I began writing this book, “Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Jew: Learning to Love the Lessons of Jew-Hatred,” two years before the October 7th massacre. Truth be told, I had been sitting on it, unwritten, for more than 30 years, never feeling the time was right.

After my personal Jewish wake-up in high school, I went on a journey of intellectual and spiritual exploration beginning with my university studies and continuing in yeshiva Torah study. I had hesitated to write because, although the conclusions are very meaningful, the ideas challenge conventional wisdom, sacred cows, and what I would call the ‘orthodoxy’ in much of academia and the Jewish world.

I am not afraid of speaking my mind, stirring controversy, or going against the mainstream, nor do I mind being disliked, but I didn’t think the ideas would be heard, and I didn’t want to waste my time and breath. With a generation more open to new ideas and enough distance from the Holocaust, I thought my somewhat radical approach could be considered objectively and not simply rejected due to cognitive dissonance.

That is my wish, at least — that with this book, I can help deepen our conversation around the meaning of both Jew-hatred and the Jewish People.

Jews are experiencing a new world — seeing a side of the world they either didn’t know or thought no longer existed. As New York University student Bella Ingber testified to Congress:

“Being a Jew at NYU is being surrounded by students and faculty who support the murder and kidnapping of Jews because, after all, as they say, resistance is justified. It is being surrounded by social justice warriors and self-proclaimed feminists, whose calls for justice end abruptly when the rape victims are Jews. Being a Jew at NYU is experiencing how diversity, equity, and inclusion is not a value that NYU extends to its Jewish students. Today … at NYU, I hear calls to gas the Jews, and I am told that Hitler was right.”

Many Jews are now wondering what is happening. How do we make sense of this new reality? Is there something bigger behind the hate, or to being Jewish? These questions are on the minds of many, Jews and non-Jews, but cogent answers are hard to find.

Jewish identity, as it was presented to me and my generation, seemed to revolve around remembering the Holocaust and a few cultural tidbits like bagels and lox. For me, antisemitism was not a reason to be Jewish, and anyone can eat a bagel.

I wanted a positive reason to be Jewish, if there was one. And if there wasn’t, well, then it was time to move on. I also wanted to be like everyone else. I thought I was — I played hockey, partied, and enjoyed everything my suburban Canadian life had to offer. But just when I thought I might leave Judaism behind, I began to discover reasons to stay.

At age 20, my twin brother found God. I thought he was nuts … at first. We had always been competitive, and that did not change with his newfound religiosity. We debated. I asked him a lot of questions and was surprised that he had intelligent responses. It got me thinking, for the first time, about deep life questions.

I reflected on being Jewish; although I did not believe in God, I had to admit there was an unarticulated sense in me that we, as Jews, were distinct in some way. Any time I met a fellow Jew, it felt a bit like we were family. To move forward, I needed answers to my basic Jewish questions:

Was there an explanation for my feelings of being part of a larger family?

Was there a reason for antisemitism, for the peculiar constancy of enmity against us?

How do we explain the outsized Jewish impact on the world?

How did we survive for so long?

I wanted to go beyond the conventional wisdom and insufficient narrative I had been given in Hebrew school, synagogue, and family holiday gatherings.

I dove in to understand what being Jewish is about. I wanted to know how and why the Holocaust could have happened in the modern world — what were people thinking? I studied classical Jewish texts about the Jewish People and explored why antisemites say they hate Jews.

I delved into texts some might avoid, including Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” (“My Struggle” in German) and everything he wrote or said that was available in English. Studying Hitler, I learned he had a clearly articulated ideology; this surprised me because I had always thought he was a raving lunatic. His own writings and speeches made it clear that the complete elimination of the Jews in Europe was, to him, the logical conclusion of his ideology.

As we delve deeper, an even more remarkable and mind-bending revelation emerges. Not only do both Jew-haters and Jew-lovers acknowledge the power and influence of the Jews, but Nazism and Judaism share many basic foundational ideas.

Astonishingly, these two worldviews — Jewish philosophy (hashkafa in Hebrew) on the one side, and Hitler’s weltanschauung on the other — are mirror images of each other, with the two standing on opposite moral corners.

Jewish philosophy and tradition would say that Adolf Hitler was right about the nature of man’s struggle and the Jewish People’s disruptive impact, but he was dead wrong morally.

Nietzsche, Hitler, and many others believed that a Jewish worldview had transformed Western civilization. The Nazis believed that the Jews invented world-changing ideas for devious purposes, to weaken and devastate humanity. Jews, on the other hand, believed that they were given a set of powerful ideas as part of a divine mission.

To Hitler, man was just another animal in an uncaring, random social Darwinian universe. To the Jews, man (all human beings) is a being created just short of the angels, in the image of God, souls of infinite value.

According to Nazi ideology, one great conflict drove all of human history: the battle over humanity’s self-definition — the “honor” concept of nature which Hitler sought to revive versus the Jewish “human” concept. The future of humankind depended on adherence to nature’s laws of might and survival, and so necessitated the defeat of the humanitarian values of love, brotherhood, and tolerance that Jews had taught and that had become pervasive in Western civilization.

Judaism agrees with Hitler (and Nietzsche) that humanity is engaged in a battle that strikes at the core of the human condition. It is the battle of soul versus body, good versus evil, holy versus profane. In Nazi words, this was the conflict between the “human concept” and the “honor concept.”

Jewish tradition agrees with Nietzche that it was they who disrupted and transformed a world comfortable in “the master morality.” In fact, 3,800 years ago, a deep-thinking genius named Abraham searched philosophically, and what he found changed the world. This is where the Jewish story begins, with the first Jew.

Abraham’s discovery of God — infinite yet personal — was humanity’s greatest discovery. And Abraham went further. He questioned, formulated, and articulated a complete system of philosophy and ethics that was world-shattering. These principles became the foundations of Judaism; Abraham had accessed the Divine life principles that seven generations later were concretized at the great revelation of the Torah at Mount Sinai.

Judaism believes that all human history — and, thus, every individual human life — is the story of this battle with the human condition. And that salvation, both personal and global, is dependent upon the victory of the human concept. Best-selling author Rabbi Simon Jacobson says it well:

“The struggles to integrate the Divine and the human, matter and spirit, body and soul, the inner and the outer, are as old as history itself. The tension between these opposing but complementary forces lie at the root of all conflict: inner (personal) and outer (social and political).”

Hitler said: “No nation will be able to withdraw or even remain at a distance from this historical conflict.”

The Nazis believed that spirituality dehumanizes man, while Judaism holds that man humanizes the universe. The Torah illustrates this worldview eloquently through the story of Rebecca. While still in her womb, Rebecca’s twins fought desperately, causing her such anguish and pain that she sought out a prophet to explain the unusual nature of her pregnancy.

The prophet revealed that she was carrying two diametrically opposed leaders. The 19th-century Jewish philosopher Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch explained the prophetic response:

“Rebecca was informed that she carried two nations in her womb who would represent two different forms of social government. The one state would build up its greatness on spirit and morals, on the humane in humans, the other would seek its greatness in cunning and strength.”

“Spirit versus strength, morality versus violence oppose each other, and indeed, from birth onwards will they be in opposition to each other. ... The whole of history is nothing else than a struggle as to whether spirit or sword, or, as our sages put it, whether Caesarea or Jerusalem is to have the upper hand.”

Judaism and Nazism share a common worldview: there is another world war, one more significant than the battles fought with guns and tanks — an epic ideological struggle. The Nazis fought on the side of brute force and the Jews on the side of love. One side wielded the might of a vast army and empire; the other commanded an empire of the spirit. The Nazis sought to destroy the moral power of the Jews with raw force, through degradation and deprivation, killing millions, and yet they could not achieve their goal.

The cults of personality of totalitarian regimes, with their claims of master races and utopian visions, are futile attempts to manufacture the illusion that their power can overcome human failings. Their followers are taught that they do not need to engage in a personal reckoning if they believe in the power of the Führer or the Beloved Leader and devote all their energies to fighting for him.

Judaism offers no such escape from personal responsibility. Instead, it demands, as the essence of faith, a morality that comes from a constant dialogue with a personal God.

Hermann Rauschning, a former Nazi, tried to alert the world to these ideas. As the President of the Senate of the Free City of Danzig from 1932 to 1934, he had several conversations with Hitler, which led him to subsequently reject the Nazi movement and make his way to the US. He wrote several books before and during the war in a desperate attempt to show the free world that Nazism was a serious threat, warning:

“The new element (Nazism) is, at the same time, of immemorial age. It is the demon of destruction, which had been banned from our normal life by civilization. It is the craving, suddenly grown to immense urgency, to throw off domestication and all civilized restrictions ... Be not deceived: this urge to return to the primitive is felt not only by the Germans. Among the masses everywhere there is the same strong desire to throw off the burdens and obligations of a higher humanity.”

This is the same human struggle that author Fyodor Dostoevsky so powerfully described through the character of Ivan Karamazov in his novel, “The Brothers Karamazov.”

Set in Spain during the bloody days of the Christian Inquisition, Jesus appears and is arrested by the Grand Inquisitor, who proceeds to lecture him. The Inquisitor argues that Jesus’ mistake and sin was expecting too much of humanity; by placing on people the moral burden of freedom and a moral code, he demanded too much.

For this sin, the Inquisitor plans to burn Jesus at the stake for imposing the Judeo-Christian worldview:

“You want to go into the world … with some promise of freedom which they (humanity) in their simplicity and innate lawlessness cannot even comprehend, which they dread and fear — for nothing has ever been more insufferable for man and for human society than freedom!”

This conflict is the fault line of the human condition: On this point, the Torah, Hitler, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche agree. Hatred takes root precisely against the “terrible burden” of “freedom of choice.”

The existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre also recognized that it is on this fault line where the heart of Jew-hatred lies. Having lived in Paris through the Nazi occupation during World War Two, Sartre wrote Anti-Semite and Jew in 1944, charging that antisemitism stems from something fundamental in human nature — the fear of the responsibility of being human:

“We are now in a position to understand the anti-Semite. He is a man who is afraid ... of himself, of his own consciousness, of his liberty, of his instincts, of his responsibilities, of solitariness, of change, of society, and of the world. ... In espousing antisemitism, he does not simply adopt an opinion, he chooses himself as a person. He chooses the permanence and impenetrability of stone, the total irresponsibility of the warrior who obeys his leaders ... antisemitism, in short, is fear of the human condition.”

Beginning with Abraham, a spiritual revolution emerged that introduced a new outlook into the world. This revolution was so successful that 3,800 years later, one of the most powerful nations in the world, Germany, launched a campaign of genocide to eradicate it.

Hitler observed, with fear and disgust, that most of the modern world had embraced the ideas brought to the world by Abraham and the revelation at Sinai. These Jewish teachings promote values that are now widely accepted: classic Western liberalism, rejecting the primitive ideals of “might makes right,” and instead striving for equal and human rights and the dignity and sanctity of life.

They advocate for caring for the oppressed and downtrodden, promoting universal education, creating social welfare programs to help the sick and needy, encouraging tolerance, working to end racism, and fostering peace and the end to violence and war.

These ideals, which are fundamental to Judaism, were not widely accepted when they were first introduced. It is no coincidence that one of the freest countries in human history has a verse from the Hebrew Bible inscribed on its Liberty Bell: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

It is also no coincidence that the global institution tasked with working for world peace, the United Nations, takes its vision from the Jewish prophet Isaiah: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.”

But over the thousands of years that it took humanity to get to where it became self-evident that “all men are created equal,” there has been resistance every step of the way. There is a body-soul push and pull through history; as the lofty and holy ideas are slowly and painfully integrated into civilization, they are simultaneously resisted.

The pushback is called antisemitism.

This chimes with things I've been thinking recently. Our enemies understand us better than we often do ourselves. They are a mirror in which we can see our strengths and core values reflected. I'll look out for the book!

Brilliant commentary! One that's worthy of reading and internalizing for every human on planet Earth.