Most people are not antisemites, but that is not the point.

As a makeshift sign I recently saw in Israel said: "Tolerating antisemitism is antisemitism."

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

In the late 19th century, Sudan was a loosely governed territory under Egyptian control, itself a vassal of the Ottoman Empire.

This control was propped up by British imperial interests, and the region was rife with social and economic discontent due to heavy taxation, corruption, and the brutal suppression of local autonomy.

Muhammad Ahmad, a charismatic Sufi preacher from a remote part of Sudan, began preaching a message of religious and moral reform. He condemned the corruption of the Ottoman-Egyptian rulers and called for a return to a purer form of Islam. His message resonated with a population weary of oppression and economic hardship.

Initially, his movement was dismissed as a fringe sect, but Ahmad's claim to be the Mahdi — a messianic figure prophesied to bring justice — galvanized followers. Combining religious fervor with military organization, the Mahdists launched a jihad against the ruling authorities.

Despite being vastly outnumbered and outgunned, the Mahdists’ discipline and ideological zeal allowed them to defeat larger and better-equipped forces. In 1885, they captured Khartoum, killing the British-appointed governor, General Charles Gordon, in a stunning victory that sent shockwaves through the British Empire.

For the next 13 years, the Mahdists controlled Sudan, imposing their vision of Islamic governance. Their regime was marked by strict theocratic rule, suppression of dissent, and aggressive enforcement of religious orthodoxy. While some welcomed the end of foreign rule, many Sudanese suffered under the Mahdists’ harsh laws and economic mismanagement.

The Mahdist Revolt is a textbook example of how a small, ideologically driven group can seize power in the right circumstances. Their success was rooted in a combination of charismatic leadership, popular discontent, and the weaknesses of the incumbent rulers.

More broadly, it illustrates how fringe movements can exploit societal grievances, religious or ideological fervor, and organizational discipline to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds. It also shows how such movements, once in power, often impose their will in ways that dramatically reshape society, for better or worse.

The Mahdist state eventually fell to an Anglo-Egyptian reconquest in 1898, but its brief dominance left a lasting legacy in Sudanese history, demonstrating the power of a committed minority to rewrite the rules of governance and social order.

Such is the case with antisemites — on both sides of the sociopolitical Left and Right. They are fringe groups, while the comforting narrative of history often assures us that most people are, at their core, reasonable. We are told to find solace in the belief that decency is the silent majority’s default setting, and extremism is the noisy anomaly destined to fizzle out.

But history, ever the inconvenient debunker of human optimism, tells a darker, more cautionary tale: Fringe movements, even when composed of a minority, can reshape societies, reframe political landscapes, and wreak havoc far beyond their numbers. Unfortunately, the opinions of “most people” often do not matter until it is too late.

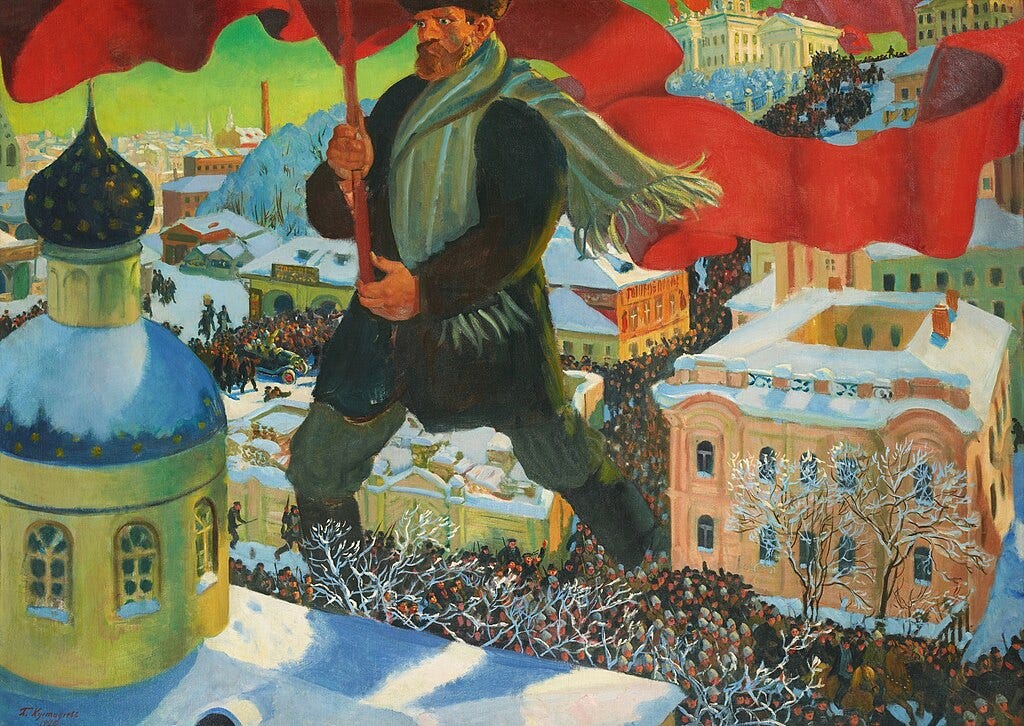

From the French Revolution’s Jacobins to the Bolsheviks of Russia, and from 20th-century fascist movements to extremist factions in contemporary democracies, history teems with examples of small groups punching far above their weight. These movements often began as marginal or laughable, yet they wielded outsized influence through discipline, an unrelenting sense of mission, and the apathy or acquiescence of the majority.

Take the Nazis. It bears repeating, painfully and persistently, that the Nazi Party did not win a majority of votes in Germany’s 1933 elections. They ascended through a mix of political maneuvering; opportunistic alliances; and a society either too divided, too fearful, or too indifferent to stop them. The bulk of Germans were not rabid antisemites, nor did most dream of racial hierarchies or genocidal wars. Yet antisemitism, central to Nazi ideology, became state policy — and the silent majority enabled it through its silence.

The Bolsheviks were similarly an unrepresentative minority at the time of the Russian Revolution. Lenin’s faction of the Russian Social Democratic Party did not command widespread support; they simply out-organized their rivals and exploited societal chaos. Before long, they turned their ideological zeal into a machinery of control that coerced, terrorized, and starved millions.

History’s minority movements have always been buoyed by a familiar dynamic: the inertia of the mainstream. While the fringes agitate and organize, the majority procrastinates, rationalizes, and — when push comes to shove — compromises, not because they do not care, but because they are too busy to think twice about most things. Due to socioeconomic issues such as inflation, most Westerners are endlessly busy with the struggle for day-to-day economic sustenance.

They are also too busy to learn history, especially a history that is not exactly theirs. They might know about or have heard about the Holocaust, but does the average Westerner understand all the geopolitical and socioeconomic nuances that led the Nazis to slaughter six million Jews in six years? Probably not, and it does not matter how many movies we make or museums we build about the Holocaust.

Nor is this a condemnation of the so-called “silent majority.” It is simply an observation of human nature. Most people, in most societies, prefer the path of least resistance. They trust that the status quo will hold because it always has — or so it seems. They might shake their heads at troubling headlines or mutter a disapproving “tsk-tsk” at unsettling news, but they assume someone else — a politician, an activist, a journalist, a neighbor — will handle it.

It is not that they do not care; it is that their attention is elsewhere: on careers, children, debt, caring for someone sick or elderly. The machinery of daily life grinds relentlessly on, leaving little time to ponder the warning signs flashing on the edges of society.

But history is merciless to those who fail to heed its lessons. And history, inconvenient as it is, shows us time and again that the fringes thrive not in a vacuum, but in the blind spots of the majority. It is in those overlooked spaces that small, determined minorities plant their seeds of influence. The majority, distracted and overwhelmed, often fails to notice until those seeds have grown into invasive weeds, choking the very roots of society.

This dynamic is all the more magnified when the majority does not feel personally implicated by the threat at hand. Why learn about the long shadow of antisemitism if you are not Jewish? Why study the mechanics of othering when it is not your group being othered? The majority assumes these battles belong to someone else, comfortably confident that the tides of extremism will not reach their shores. After all, they are not antisemites, so what does it have to do with them?

Yet this is precisely the point. The success of fringe ideologies rarely depends on converting the masses to their cause. It depends on the apathy of the uninvolved and the inertia of the indifferent. It is not about whether most people are antisemites; it is about whether most people care enough to act when antisemitism begins to slink back into the mainstream, wearing new disguises and speaking in dog whistles rather than bullhorns.

History’s great tragedies — pogroms, genocides, inquisitions, and more — were not powered by universal hatred. They were powered by a minority of zealots, unopposed by a majority too preoccupied to question, resist, or intervene. The Jacobins did not need all of France to embrace the guillotine; they only needed most of France to keep its head down (pun tragically intended). The same goes for the Nazis, who built their empire of horror on a foundation of fear, propaganda, and the resigned compliance of millions who told themselves that it was not their fight.

So yes, most people are not antisemites — but that is not the point. The point is that most people, left unchecked, will also not stand in the way of antisemites. And therein lies the danger: While the majority procrastinates, rationalizes, and compromises, the fringes never rest. They organize, they strategize, and they exploit the spaces where the busy majority’s vigilance falters. By the time the majority looks up from its distractions, it is often too late.

Yes, it is true: Most people in the West are not inherently driven by ideology. Most people want stability, security, and a general sense of normalcy. Extremists, on the other hand, want upheaval — and they work tirelessly to achieve it. The mismatch in energy, focus, and ruthlessness creates an uneven playing field.

Fringe ideologues also understand a vital truth about human nature: Fear is a more powerful motivator than reason. A tiny, determined group can cow the majority into submission if it stokes the right fears, whether through propaganda, violence, or the strategic targeting of scapegoats. The majority does not need to believe in the ideology — it just needs to feel powerless to oppose it.

Consider the scapegoating of Jews, a tactic so tragically recurrent in history that it might as well be its own subgenre. From medieval pogroms to modern conspiracies, Jews have served as a convenient “other” for societies looking to explain economic hardships, political failures, or social anxieties. It is not that most people actively hated Jews, but enough were willing to tolerate — or even participate in — anti-Jewish actions when whipped into a frenzy by a vocal minority.

This dynamic is not confined to history books. In our hyperconnected, algorithm-driven world, fringe movements enjoy unprecedented tools for influence. They do not need to command armies or take over parliaments immediately; they only need to shift the Overton window — the range of ideas considered acceptable in public discourse.

Take the rise of antisemitic tropes in modern politics and pop culture. While Right-wing Nazi-inclined antisemitism remains taboo in much of mainstream society, Left-wing antisemitic voices work diligently to repackage ancient hatreds for modern consumption. They target celebrities, politicians, and cultural institutions through subversion that comes with a slick rebrand.

The modern antisemite is a savvy marketer, a political strategist with a sixth sense. Instead of shouting, they whisper. Instead of openly blaming “the Jews,” they deploy euphemisms: “colonialists,” “bankers,” “elites.” They know their audience and how to bait the hook. They package these tropes not as hatred, but as edgy skepticism, rebellious inquiry, or even a popularity contest. It is not antisemitism, they assure you — it is just asking questions.

Social media platforms have become the perfect vector for these repackaged hatreds. Algorithms, designed to maximize engagement and feed us what we will click on, unwittingly amplify social media posts disguised as “hot takes.” A cleverly edited video, a meme, or a seemingly harmless quip can plant a seed of suspicion in millions of minds, ready to bloom into prejudice when watered by further exposure. Platforms that once promised to democratize knowledge now serve as echo chambers, amplifying fringe ideas until they no longer seem fringe.

This is the playbook: Subvert the mainstream by targeting its most visible symbols. Fringe voices go after celebrities who dare to speak against injustice, painting them as pawns of shadowy cabals. They target politicians who embrace pluralism, accusing them of being “controlled.” And they attack cultural institutions — films, universities, even libraries — as part of a larger conspiracy to erode “traditional values.” The point is not to convince everyone outright; it is to sow enough doubt and suspicion that the toxicity seeps into public consciousness, drip by insidious drip.

The brilliance — and the danger — of this strategy lies in its subtlety. Outright hate is easy to spot and reject, but dog-whistles are harder to decipher. They give plausible deniability to both the speaker and their audience. “Oh, I didn’t mean it that way,” they claim, while their followers nod knowingly. The result is a cultural gaslighting that leaves even the most well-meaning individuals questioning their instincts: “Was that antisemitic, or am I overreacting?”

This subversion is not just a fringe activity; it is a deliberate attempt to normalize the unthinkable by embedding it in the everyday. It is why the fight against antisemitism — and all forms of hatred — requires constant vigilance. Once these tropes infiltrate the mainstream, they are far harder to extract. And while the majority may not actively support such views or buy into these narratives, their failure to notice or challenge them gives these ideas the breathing room they need to grow, creating an environment where antisemitism no longer shocks but merely “exists.”

The point, then, is not to comfort ourselves with the knowledge that most people are not antisemites, fascists, or extremists. It is to recognize that the moral compass of society is not set by the majority, but by those who act. Silence, indifference, and inaction are the real handmaidens of fringe dominance.

This is where we must resist the complacency of numbers. It is not enough to avoid antisemitism ourselves or to dismiss extremists as irrelevant because they are few. It is incumbent upon us to confront, counter, and dismantle their influence at every turn. To call out the dog whistles. To educate the apathetic. To refuse to yield the public square.

“Most people” being decent is only meaningful if that decency translates into action. After all, it was not “most people” who changed the world for the worse; it was the few who were willing to fight in accordance with their worst instincts. Our task is to ensure that the decent majority does not remain silent, lest it allow history to repeat itself.

As usual, a brilliant analysis of where we find ourselves today, Joshua. It feels, right now, a bit like being sucked down a drain. Yet again, CBC lead the radio news this morning with its lopsided coverage of suffering in Gaza, so, while your points about indifference are truly devastating, I think you underestimate the numbers of the antisemitic relative to the indifferent. So many have already been brainwashed by the media, social media, and their friends and family.

When a Black man died from having a knee compressing his neck, the mobilization was quick and vast and DEI was implemented and everything became "racist," and members of Congress wore African scarves and --I could go on and on. The entire country denounced "racism." When Asians were being attacked for a brief period of time during Covid, a large "Stop Asian Hate" campaign spread quickly. Russia attacks Ukraine? Big mobilization for Ukrainian support. But, yet again, even in the face of obvious and persistent world-wide Jew Hate, we can't get people mobilized to help us. Politicians in America and around the world do nothing or very little and many are antisemites themselves. The media makes it worse by constantly blaming Israel for everything. No matter how bad it gets for the Jews, no matter what might happen, I have little faith that "most people" will say or do anything to stand up for us. What to do?