Myth Busted: Israel and the Holocaust

Many people think Israel was created because of the Holocaust, but using this logic irresponsibly erases other parts of history that are also important to understanding the critical need for Israel.

Editor’s Note: In light of the situation in Israel — where we are based — we are making Future of Jewish FREE for the coming days. If you wish to support our critical mission to responsibly defend Israel and the Jewish People during this unprecedented time in our history, you can do so via the following options:

You can also listen to this essay instead of reading if you prefer:

In many circles, the prevailing belief is that the State of Israel was created in 1948 specifically because of the Holocaust (which ended in 1945).

I used to think this too after I moved from my hometown Los Angeles to Israel in 2013.

But a few years ago, I started to learn that the State of Israel was not created in 1948 specifically because of the Holocaust. The years of circa 1850 to 1930 are equally critical to the creation of Israel in 1948 — far before the rise of antisemitic Nazi Germany and the subsequent start of the Holocaust in 1939.

This is critical to understand since, if Israel was created because of the Holocaust, then many could make the case that there’s an exponentially lesser need for a Jewish state nowadays, since we are pretty far removed from the Holocaust, and the Jews have rebuilt themselves in many places across the world, where they are strong and plentiful (relatively to the number of Jews worldwide immediately after the Holocaust).

But when you realize that Israel was not created simply because of the Holocaust, everything changes. Suddenly, you understand that a Jewish state is still very much imperative for — among many other reasons — the continuance of these strong and plentiful Jewish communities across the world, while ensuring the ongoing safety and confidence that Jews have to be Jewish virtually wherever they are in the world (except for the countries that are hostile toward Jews).

And you also realize that Hamas’ brutal attack on Jewish babies and toddlers, music festival goers, Holocaust survivors, and hundreds of other citizens was, in some ways, an attack on Jews across the world.

The idea of “Jews across the world” began following the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. A healthy majority of Jews ended up in Arab countries.

“You have to understand that for us Jews, the natives of the Arab countries, the State of Israel was not created because of the Holocaust, but because we wanted to realize a millennial dream (the return to Israel),” said Laly Derai, who was born in Paris to parents who first immigrated from Tunisia to France.

When modern Zionism started to gain traction in the 1800s, Mizrachi and Sephardic Jews (those from North African and Middle Eastern countries) increasingly faced expulsion or intense social pressure to leave these countries simply because they were Jewish. And the vast majority of them returned to what is today Israel, including many Yemenite Jews in the 1800s.

Most of them arrived in Israel after the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, when expulsion or intense social pressure by Arabs against Jews was severely heightened. Between 1948 and the early 1980s, more than 850,000 Jews left or were expelled from countries in the Middle East and North Africa. In 2005, 61-percent of Israeli Jews were of full or partial Middle Eastern or North African ethnicity.

But, as I wrote at the beginning of this essay, the so-called return to Zion in its modern sense began circa 1850. In that year, the American Consul Warder Cresson, a convert to Judaism, established legal Jewish settlements near Jerusalem.

When Jews started arriving to Palestine in the late 1800s, many of them purchased land. Petah Tikva was founded in 1878 by ultra-Orthodox Jewish pioneers who bought properties from two Christian businessmen.

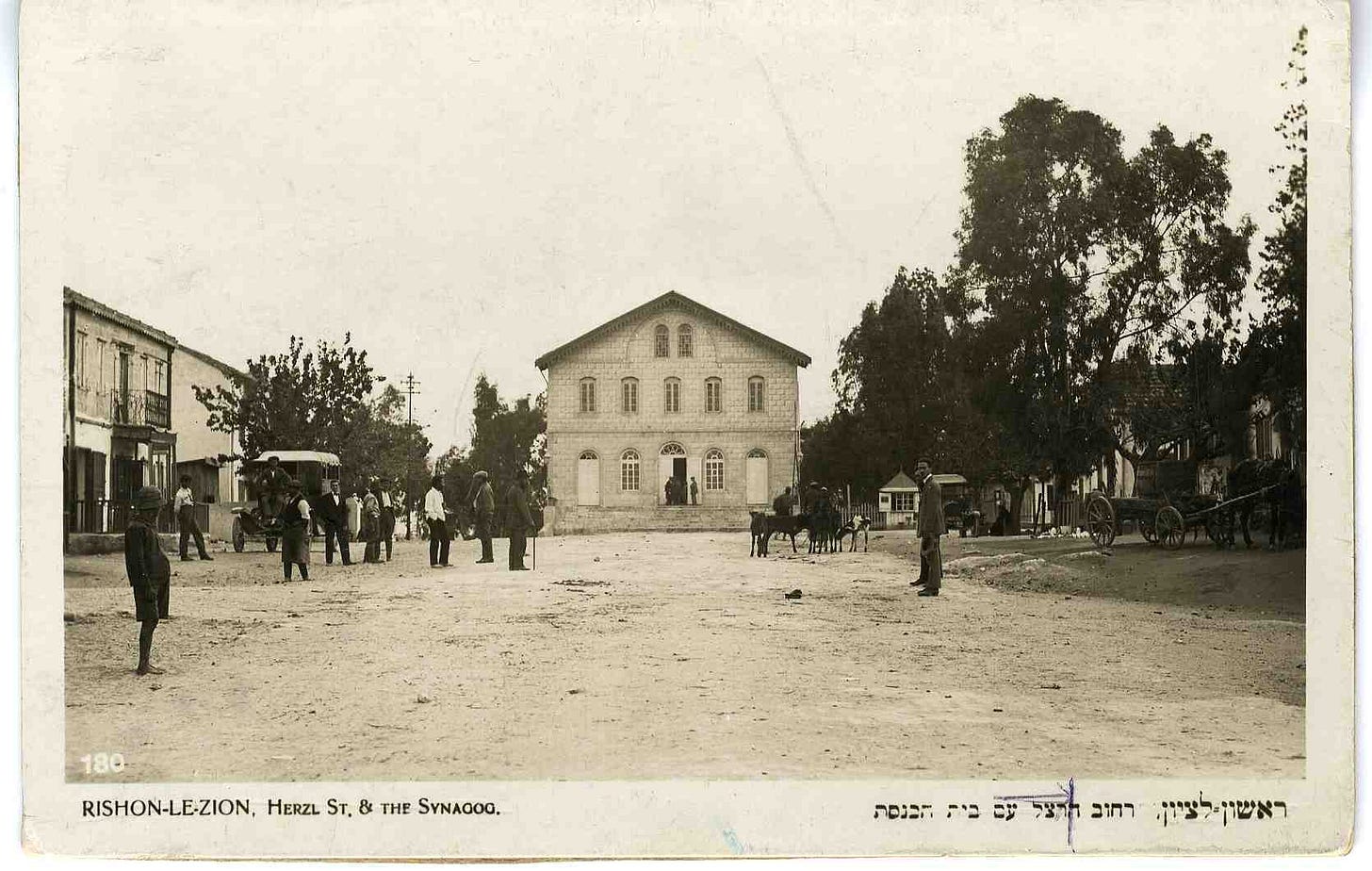

And in 1882, Haim Amzaleg purchased 835 acres of land from Mustafa Abdallah ali Dajan — in what is today Rishon LeZion, an Israeli city south of Tel Aviv — which created “a convenient launching pad for early land purchase initiatives which shaped the pattern of Jewish settlement until the beginning of the British Mandate.

Sir Moses Montefiore, famous for his intervention in favor of Jews around the world, established a legal colony for Jews in Palestine. In 1854, his friend Judah Touro bequeathed money to fund Jewish residential settlement in Palestine. Montefiore was appointed executor of his will, and used the funds for a variety of projects, including building the first legal Jewish residential settlement and almshouse outside of the old walled city of Jerusalem in 1860 — today known as Mishkenot Sha’ananim.

The official beginning of the construction of the “New Yishuv” — Jewish residents in Palestine — is usually dated to the arrival of the Bilu group in 1882, which commenced “The First Aliyah.”

Most immigrants came from the Russian Empire, escaping the frequent pogroms and state-led persecution in what are now Ukraine and Poland. They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe.

Additional aliyah followed the Russian Revolution and its eruption of violent pogroms. In 1885, the Great Synagogue of Rishon LeZion was founded, just a few kilometers south of present-day Tel Aviv.

In the 1890s, Herzl infused Zionism with a new ideology and practical urgency, leading to the First Zionist Congress in Switzerland in 1897, which created the World Zionist Organization. From 1897 to 1901, the Zionist Congress met annually, and thereafter biennially.

In 1904, “The Second Aliyah” saw an additional 35,000 Jews arrive, mostly from the Russian Empire, and some more from Yemen. Among them was David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel’s eventual first prime minister.

In 1921, Golda Meir (who went on to become Israel’s first and only female prime minister) arrived on the scene. And that same year, Albert Einstein attended a fundraiser to establish the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Lobbying by Chaim Weizmann — one of the founders of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Israel’s first president — culminated in the British government’s Balfour Declaration of 1917. It endorsed the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, as follows:

“His Majesty’s government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

During the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, an Inter-Allied Commission was sent to Palestine to assess the views of the local population; the report summarized the arguments received from petitioners for and against Zionism. In 1922, the League of Nations adopted the declaration, and granted to Britain the Palestine Mandate:

“The Mandate will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home ... and the development of self-governing institutions, and also safeguard the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.”

Jewish migration to Palestine and widespread Jewish land purchases from feudal landlords contributed to landlessness among Palestinian Arabs, fueling unrest. Riots erupted in Palestine in 1920, 1921, and 1929, during which both Jews and Arabs were killed.

Britain was responsible for the Palestinian mandate and, after the Balfour Declaration, it supported Jewish immigration in principle. But, in response to the violent events noted above, the Peel Commission published a report proposing new provisions and restrictions in Palestine.

In 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany, and in 1935 the Nuremberg Laws made German Jews (and later Austrian and Czech Jews) stateless refugees. Similar rules were applied by the many Nazi allies in Europe. The subsequent growth in Jewish migration and the impact of Nazi propaganda aimed at the Arab world led to the 1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine.

Again, Britain established the Peel Commission to investigate the situation. The commission did not consider the situation of Jews in Europe, but called for a two-state solution and compulsory transfer of populations. Britain rejected this solution and instead implemented the White Paper of 1939, which planned to end Jewish immigration by 1944 and to allow no more than 75,000 additional Jewish migrants.

At the end of the five-year period in 1944, only 68-percent of the 75,000 immigration certificates provided for had been utilized, and the British offered to allow immigration to continue beyond the cutoff date of 1944, at a rate of 1,500 per month, until the remaining quota was filled.

The growth of the Jewish community in Palestine and the devastation of European Jewish life sidelined the World Zionist Organization. The Jewish Agency for Palestine under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion increasingly dictated policy with support from U.S. Zionists who provided funding and influence in Washington, D.C., including via the highly effective American Palestine Committee.

During World War II, as the horrors of the Holocaust became known, the Zionist leadership formulated the One Million Plan, a reduction from Ben-Gurion’s previous target of two million immigrants.

Following the war’s end, a massive wave of stateless Jews, mainly Holocaust survivors, began migrating to Palestine in small boats in defiance of British rules. The Holocaust united much of the rest of world Jewry behind the Zionist project, but the British either imprisoned these Jews in Cyprus or sent them to the British-controlled Allied Occupation Zones in Germany.

The British, having faced the 1936-1939 Arab revolt against mass Jewish immigration into Palestine, were now facing opposition by Zionist groups in Palestine for subsequent restrictions.

In January 1946, the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry was a joint British and U.S. committee set up to examine the political, economic, and social conditions in Palestine as they bore upon the problem of Jewish immigration and settlement, and the well-being of the peoples living there; to consult representatives of Arabs and Jews; and to make other recommendations “as necessary” for an interim handling of these problems, as well as for their eventual solution.

Following the failure of the 1946-1947 London Conference on Palestine, at which the United States refused to support the British, the British decided to refer the question to the United Nations on February 14, 1947.

In May 1947, Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko told the United Nations that the Soviet Union supported the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state, and the Soviets formally voted this way in the United Nations in November 1947.

That year, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine recommended that western Palestine should be partitioned into a Jewish state, an Arab state, and a UN-controlled territory: Corpus separatum, around Jerusalem.

This partition plan was adopted on November 29, 1947, with United Nations GA Resolution 181, 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The vote led to celebrations in Jewish communities and protests in Arab communities throughout Palestine.

Violence throughout the country, previously a Jewish insurgency against the British, with some sporadic Jewish-Arab fighting, spiraled into a war from 1947 to 1949 known in Israel as the War of Independence and in Arabic as al-Nakba (“the disaster”).

After World War II and the destruction of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe, Zionism became dominant in the thinking about a Jewish national state. The movement was eventually successful in establishing Israel on May 14, 1948, as the homeland for the Jewish People.

The proportion of the world’s Jews living in Israel has steadily grown since the movement emerged. By the early twenty-first century, more than 40-percent of the world’s Jews lived in Israel, more than in any other country. Today, there are about 6 million Jews living in Israel, of the total 15 million Jews worldwide.

This is all to say that Israel was not created simply because of the Holocaust, and using this logic irresponsibly erases other parts of history that are also important to understanding why Israel matters now more than ever. It also disrespectfully overlooks the Middle Eastern and North African Jews who were mostly unaffected, at least directly, by the Holocaust — and who today make up a significant portion of Jews worldwide.

Please do not misunderstand me: Virtually all Jews of all backgrounds agree that the unconscionable evils of the Holocaust, and the six million Jews murdered, were an enormous trigger to Israel’s founding in 1948, but the Holocaust did not live in a vacuum.

And if it was not for the aforementioned 1850-to-1930 series of events, it’s highly unlikely that the Jews would’ve created and been approved by the United Nations to have their own country.

Ben Shitrit, a producer and artistic director at one of Israel’s TV networks, said this kind of attitude from left-leaning Ashkenazi Israelis is “the same arrogance from the first years of the state, when they saw us as culture-less and did not understand that we have different priorities that are no less legitimate.”

According to Nissim Mizrahi, a sociologist from Tel Aviv University, politics of universality — seen from a liberal point of view as key to correcting society’s ills — are experienced by Middle Eastern Jews as an identity threat, a problem rather than a solution.

This secular, liberal worldview can lead to “enlightened racism” which “tarnishes traditional, religious, ultra-Orthodox and other peripheral communities, and negatively labels their worlds, their way of life, and their culture,” he explained, “which produces deep despair in liberals, as it turns out that they don’t have any visible option in their toolbox to buy a broad hold and win the elections.”

“I call it liberal violence, for it is the distaste shown for any religious or national expression,” Mizrahi added. “For example, strong and opinionated religious women oppose the description of gender segregation as exclusion … I don’t see how you can deny the reality that groups in society differ in their conceptions of good and bad and what a moral life is.”

It’s this same “liberal violence” that is destroying the intellectual honesty increasingly surrounding the current Israel-Hamas war.

As a result, “pro-Palestinian” demonstrations around the world have called for violent Palestinian uprisings and the gassing of Jews. They were not encouraging solidarity with Palestinians; they were celebrating dead Jews.

By better understanding the complete and intricate narratives surrounding the creation of the State of Israel, both Jews and others will have more holistic, nuanced views about the current Israel-Hamas war, which could be one of the central factors — the so-called court of public opinion — that will very well influence its outcome.