Something extraordinary is happening in Israel’s cultural world.

In response to international boycotts masquerading as principle, a creative renaissance is reshaping Israeli identity, driven by artists, innovators, and a society refusing to lose its soul.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Something extraordinary is happening in Israel’s cultural world: a quiet, defiant surge of creativity in response to a year marked by trauma, hostility, and an unprecedented global effort to push Israeli artists to the margins.

Since October 7th, countless exhibitions, concerts, film screenings, academic panels, and festival appearances have been canceled across the world. Some were halted in the chaos of the war’s first months. But many more vanished later — canceled not because of security concerns, but because of both explicit and implicit cultural boycotts masquerading as principle.

And yet, instead of dimming, Israel’s artistic world has ignited. The void left by withdrawn international performers, shuttered opportunities, and stiffened diplomatic atmospheres has been filled vigorously by Israeli creators themselves. Visual arts, theatre, music, and cinema are not merely persevering; they are undergoing a renaissance — happening not outside the context of pressure and exclusion, but precisely because of it.

Although the war is likely behind us, the return of international concerts to Israel (certainly by high-profile artists) is nowhere in sight. And the chill is not limited to performers. In September, Hollywood celebrities signed a letter vowing not to collaborate with the Israeli film industry. A number of musicians demanded their music not be distributed in Israel. And Israeli artists who openly support their own country have found themselves facing increasingly severe consequences.

The examples have piled up at dizzying speed, and these are just from this year alone:

Anta Gathering, a five-day Israeli-organized music festival in Portugal, was shut down by local police after a BDS-led campaign.

The music festival Tomorrowland, in Belgium, canceled the performance of Israeli electronic artist Skazi, citing vague “security considerations,” shortly after banning Israeli flags at the entire festival.

The International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, one of the world’s most prominent documentary events, barred notable Israeli institutions (including Docaviv, CoPro, and Kan) from participating.

At the Toronto Film Festival, a documentary about an Israeli general who rescued his family on October 7th was briefly yanked due to alleged lack of “legal clearance” for Hamas-shot footage. As director Barry Avrich said on a panel at the festival, “To the best of my knowledge, I’ve not known Hamas to have a licensing division.”

Even the world of European music competitions has not been immune. Israel was nearly kicked out of Eurovision 2026, and when it was ultimately allowed to compete (as announced in the last week), Spain, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Slovenia promptly withdrew from the competition altogether.

The pressure also extends into sports, a realm once considered resistant to political entanglement. Politicians and social campaigns insist that Israel should be treated like Russia after its invasion of Ukraine. The comparison collapses under even minimal scrutiny: Russia initiated its war; Israel did not initiate Hamas’ massacre or Iran’s regional proxy onslaught. But still, protests and disruptions have intensified at football and basketball games in Europe, cycling tours, and judo events around the world.

The message is clear: The international cultural sphere is attempting to quarantine Israel — not formally, as with Russia, but socially and symbolically.

And, yet, something unexpected happened: The reaction inside Israel was not despair, it was awakening.

At the 16th Israel Music Showcase Festival held last month throughout the country, artistic director Hadas Vananu sensed the shift immediately. This year’s event “opened something up,” she told the audience. It “feels like the start of something new.” Revital Malka from Israel’s Foreign Ministry thanked visiting delegates for offering “open ears and hearts” — a generosity Israel rarely receives today.1

Something deeper had changed. When the war broke out, the Showcase Festival abandoned its usual international delegation model and became a purely Israeli gathering of a wounded people creating, listening, grieving, and healing together. Creativity was no longer entertainment; it was community and survival, and it planted the seeds for something bigger.

Across the country, cultural institutions took similar turns inward, not as retreat, but as renewal.

In August, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art announced the addition of 35 new works by 11 contemporary Israeli artists. Sculpture, photography, textiles, painting — the breadth of mediums mirrored the breadth of voices returning to center stage. These pieces will now enter the museum’s permanent collection, expanding the canon at a moment when international museums are shrinking access.

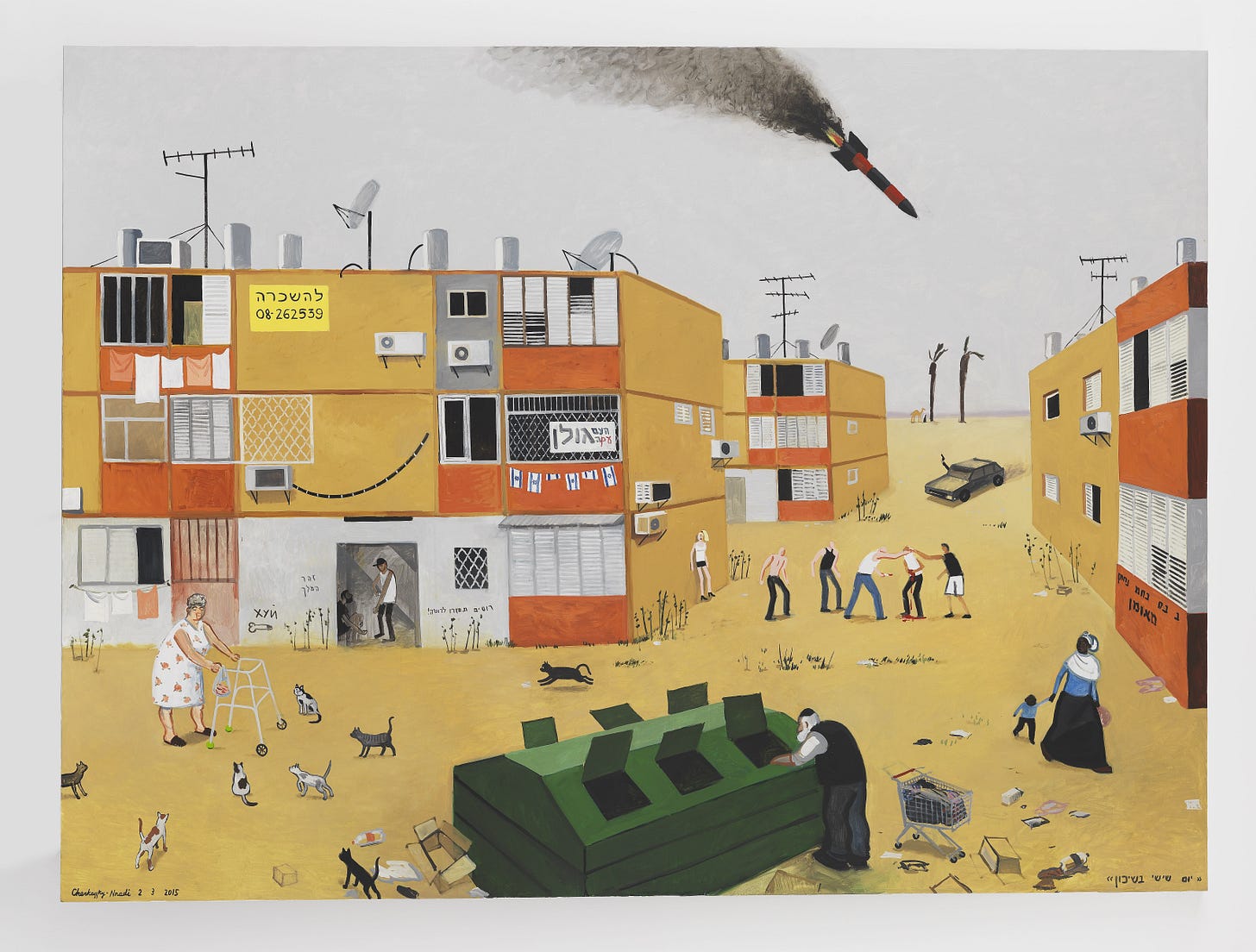

In Jerusalem, the Israel Museum responded to its 60th anniversary by completely reimagining its Israeli art collection for the first time in nearly a decade. Senior curator Amitai Mendelsohn, who designed the exhibition “Israeli Art – The Swing of the Pendulum,” explained that the goal was not historical chronology, but resonance with the present moment. He chose to explore three psychological states — reality, hope, and spirit — forms of consciousness that have always animated Israeli art but feel newly urgent today.

“You can’t ignore the context and the time we live in,” said Mendelsohn.2 “Many works have taken on new meaning, especially in light of recent events. ... We want to create a trajectory that confronts a complex reality through three psychological realms: reality, hope, and spirit. This pendulum, swinging between the here and now, and the dream or escape from it, has always existed in Israeli art.”

Israeli contemporary art has always reflected the country’s complexity, but today it feels denser, sharper, more unfiltered. Tel Aviv’s galleries — Sommer Contemporary, Dvir, Chelouche — are filled with experimental works probing identity, conflict, intimacy, and the fragile lines between public and private grief. Jerusalem’s artistic spaces, always more contemplative, are confronting sacred history, collective memory, and the weight of ritual in the aftermath of catastrophe. Artists are no longer creating with an eye toward international reception; they are creating with an eye toward truth.

The stakes feel higher. And the work reflects it.

Then there’s Israeli cinema, which may be facing the steepest barriers abroad, but it too is experiencing one of its strongest creative periods in recent memory. Women directors, in particular, have become the beating heart of Israeli cinema. They are dominating the Ophir Awards (Israel’s version of The Oscars), premiering powerful first and second films, and expanding the boundaries of what Israeli stories can be.

October 7th has opened a new chapter in how cinema portrays Israeli women. Film scholar Shmulik Duvdevani noted that Israeli cinema long revolved around the macho tsabar: Ashkenazi, male, stoic, fearless. But now, the defining stories of the war include women on the frontlines, especially the IDF’s female observers near the Gaza border.

Their story is harrowing. Sixteen observers were killed on October 7th; seven were kidnapped; one was killed in captivity; one was rescued; five returned home only in 2025. They had warned their superiors for months about an impending attack, warnings that went unheeded.

These women are now emerging as central figures in Israeli cultural memory. Talya Lavie, known for the instant-classic comedy “Zero Motivation” (2014), is creating a new film about them. Noa Aharoni’s documentary “Eyes Wide Open” (2024) has become essential viewing. And dozens of other projects, fiction and documentary, are underway.

Yet many Israeli filmmakers do not want to be quoted in international media, since they are hoping that once the war ends, film festivals will once again accept their work. Echoing what many Israeli filmmakers are feeling, one director anonymously said, “I’m no friend of Bibi, I never voted for him, and it seems crazy that my work won’t get shown because of his policies, but that’s the situation. Can you imagine if American films weren’t shown around the world because people in Europe or wherever don’t like Trump?”3

The cancellations have not been limited to film and music. At the Edinburgh Fringe Festival (often celebrated as the world’s most open, artistic, and experimental gathering), Jewish comedians Rachel Creeger and Philip Simon had their shows canceled by venue owners due to “security concerns.” In reality, organizers feared protests. Rather than protecting artists, they removed them.

The message reverberated loudly: Even Jewishness itself, let alone Israeli identity, has become grounds for exclusion in certain cultural circles.

And the response in Israel? Once again, a surge of local creation — new plays, new stand-up shows, new performance art pieces, many of them raw, wounded, exploratory, and bold.

International stages shutting their doors has forced Israeli artists to ask a radical question: Who are we creating for?

During the last decade or two, much of Israel’s cultural world felt like it was outward-facing, deeply integrated into global circuits. It still wants to be part of the world and, of course, deserves to be. But since October 7th, with invitations disappearing and doors closing, something else emerged: a recognition that Israeli culture does not need international validation to thrive.

Artists began creating for their own people. Audiences began supporting more intently. Institutions began investing more deeply. And the result is creative abundance. This renaissance is rooted in adversity, but not defined by it. It is shaped by exclusion, but animated by resilience. Israel’s artists are not shrinking; they are expanding into the spaces left empty by others.

What we are witnessing is a profound cultural realignment, a turning inward not of retreat, but of re-rooting. When foreign stages dimmed, Israeli artists flooded the vacated space with their own light. When international institutions withdrew, Israeli institutions stepped forward with new commitments, new acquisitions, new exhibitions, new festivals, new stories.

The outside world may not be listening with open ears right now. But the home audience is. And it’s all that matters.

“The Israel Music Showcase Festival brings industry professionals to scout new talent.” The Jerusalem Post.

“Fractured visions: Reimagining Israeli art.” The Jerusalem Post.

“The Israeli movies you won’t see abroad: Films from Israel that aren’t shown in other countries.” The Jerusalem Post.

This is fantastic. Please offer it to the Jerusalem Post, Times of Israel, New York Post, and other friendly papers and outlets.

If Israel's enemies only understood that the more they harass the Jews, the stronger they become, they would treat us kindly, out of spite, in the hope of weakening us.

Praise be to God!