The Story Behind Israel's Greatest (and Most Overlooked) Accomplishment

Hint: It comes impressively packaged in two Hebrew words.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free and zero-advertising for all.

Modern-day Israel and Israelis are known for a myriad of achievements: rebuilding a Jewish homeland; the world’s strongest (and most humane) military, “pound-for-pound”; Start-Up Nation; inventions like drip irrigation; Bamba; among the world’s top 20 economies in GDP per capita1 …

Oh, and Israeli cows produce the highest milk yield per cow (true story).2

Israel also finds itself placed on these per capita lists:

Most museums3

Most engineers and scientists4

Most startups5

Most expenditure on research and development (R&D) as a percentage of GDP6

Lowest rate of diet-related deaths7

Most film schools8

Most hi-tech “unicorns”9

Most vegetarians and vegans10

Second-most scientific research11

Second-most venture capital investments12

Third-most university degrees13

Fifth-most healthy longevity14

But there’s one Israeli accomplishment which often gets grossly overlooked. It comes impressively packaged in two Hebrew words: Tel Aviv.

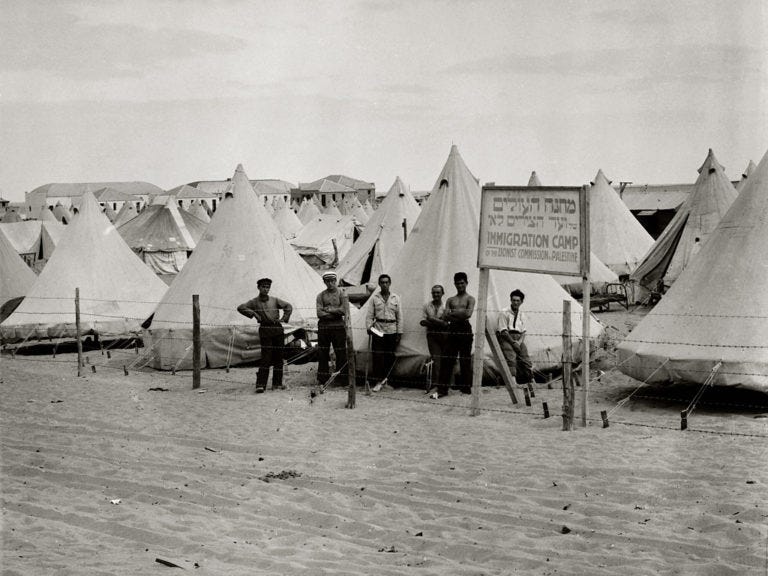

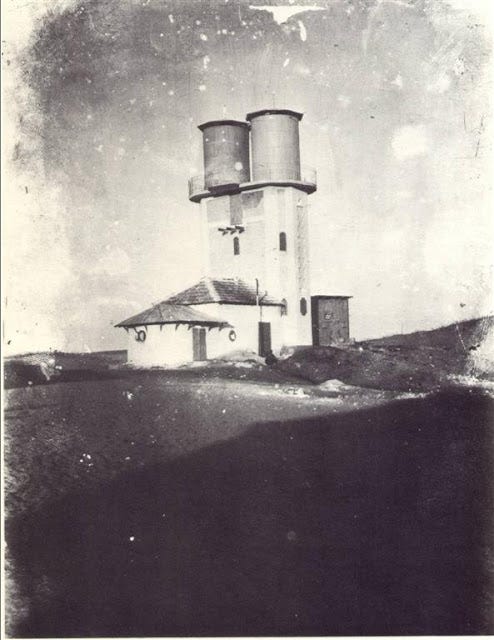

What makes “the Miami on the Mediterranean” — as National Geographic dubbed Tel Aviv — so unbelievable is where it was just a century ago. Take these pictures, for example, from the early 1900s:

The History of Tel Aviv

During the First Aliyah in the 1880s, when Jewish immigrants began arriving in the region in significant numbers, new neighborhoods were founded outside Jaffa on the current territory of Tel Aviv. The first was Neve Tzedek, founded in 1887 by Mizrahi Jews, due to overcrowding in Jaffa.15

In 1909, some 66 Jewish families gathered on a desolate sand dune in what is now Tel Aviv, to parcel out the land by lottery, a whopping total of 0.05 square kilometers (12 acres).

Akiva Aryeh Weiss, president of the building society who organized the lottery, collected 120 seashells from the Mediterranean shore, half of them white and half of them gray. The families’ names were written on the white shells and the plot numbers on the gray shells. A boy drew names from one box of shells and a girl drew plot numbers from the second box.

According to legend, the man standing behind the group, on the slope of the sand dune, is Shlomo Feingold, who opposed the idea, allegedly telling the others:

“Are you mad! There’s no water here.”16

The photographer, Avraham Soskin, happened to be roaming the area with a camera in one hand and a tripod in the other, on his way from a walk through the sand dunes of what is today Tel Aviv to Jaffa.

“I saw a group of people who had assembled for a housing plot lottery,” Soskin recounted. “Although I was the only photographer in the area, the organizers hadn’t seen fit to invite me, and it was only by chance that this historic event was immortalized for the next generations.”

The first water well was later dug at this site, located on what is today Rothschild Boulevard, the city’s main street. Within a year, other popular streets named Herzl, Ahad Ha’am, Yehuda Halevi, Lilienblum, and Rothschild were built; a water system was installed; and 66 houses (including some on six subdivided plots) were completed.

Originally called Ahuzat Bayit (literally “homestead” in Hebrew), the name Tel Aviv was adopted because the initial residents found it more suitable, since it embraced the notion of a renaissance in the ancient Jewish homeland. Aviv is Hebrew for “spring” (as in the season), symbolizing renewal. And tel is an artificial mound created over centuries through the accumulation of successive layers of civilization, built one over the other.

It turns out that Tel Aviv was also the Hebrew title of Theodor Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland (“Old New Land”), translated from German by Nahum Sokolow, who had adopted the name of a Mesopotamian site near the city of Babylon mentioned in the Book of Ezekiel:

“Then I came to them of the captivity at Tel Aviv, that lived by the river Chebar, and to where they lived; and I sat there overwhelmed among them seven days.”

By 1914, Tel Aviv had grown to more than one square kilometer (247 acres), and a census recorded a population of 2,679 the following year. However, growth halted in 1917 when the Ottoman authorities expelled the residents of Jaffa and Tel Aviv as a wartime measure, aimed chiefly at the Jewish population.

Jews were free to return to their homes in Tel Aviv at the end of the following year when, with the end of World War I and the defeat of the Ottomans, the British took control of Palestine. Suddenly, the town became an attraction to immigrants, with one local activist writing:

“The immigrants were attracted to Tel Aviv because they found in it all the comforts they were used to in Europe: electric light, water, a little cleanliness, cinema, opera, theatre, and also more or less advanced schools ... busy streets, full restaurants, cafes open until 2 a.m., singing, music, and dancing.”

According to a census conducted in 1922 by the British Mandate authorities, Tel Aviv had a population of 15,185 inhabitants, consisting of 15,065 Jews, 78 Muslims, and 42 Christians. And in 1923, Tel Aviv was the first town to be wired to electricity in all of Palestine.

The Master Plan

In 1925, the Scottish pioneering town planner Patrick Geddes drew up a master plan for Tel Aviv, which the city council adopted (led by Meir Dizengoff). Geddes’ plan for developing the northern part of the district was based on the garden city movement, a 20th-century urban planning doctrine which promoted satellite communities surrounding the central city, separated by greenbelts, with proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture.

The plan consisted of four main features:

A hierarchical system of streets laid out in a grid

Large blocks consisting of small-scale domestic dwellings

The organization of these blocks around central open spaces, and

The concentration of cultural institutions to form a civic center

While most of the northern area of Tel Aviv was built according to this plan, the influx of European refugees in the 1930s necessitated construction of taller apartment buildings on a larger footprint in the city. Ben-Gurion House was built at the outset of the 1930s, and Jewish cultural life was given a boost by the establishment of the Ohel Theatre and Habima Theatre’s decision to make Tel Aviv its permanent base, starting in 1931.

Three years later, Tel Aviv was granted the status of an independent municipality separate from Jaffa, and the Jewish population rose dramatically during the Fifth Aliyah after the Nazis came to power in Germany. By the late 1930s, Tel Aviv’s Jewish population had reached 160,000, which was more than one-third of Palestine’s total Jewish population, since many new Jewish immigrants to Palestine disembarked in Jaffa and remained in Tel Aviv, turning the city into a center of urban life.

Friction during the 1936-1939 Arab revolt led to the opening of a local Jewish port, Tel Aviv Port, independent of Jaffa, in 1938. Many German Jewish architects trained at the Bauhaus, the Modernist school of architecture in Germany, and left Germany during the 1930s. Some, like Arieh Sharon, came to Palestine and adapted the Bauhaus’ architectural outlook and similar schools to the local conditions, creating what is recognized as the world’s largest concentration of buildings in the International Style. Tel Aviv’s White City emerged in the 1930s, and became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.

According to the 1947 UN Partition Plan for dividing Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, Tel Aviv (by then a city of 230,000) was to be included in the proposed Jewish state. Jaffa (by then a city of 100,000 — 54-percent Muslims, 30-percent Jews, and 16-percent Christians) was designated as part of the Arab state.

But then a civil war between the Jews and Arabs broke out across Palestine and, in particular, between the neighboring cities, Tel Aviv and Jaffa. After several months of siege, Jaffa fell in May 1948 and the Arab population fled en masse.

Israel’s Declaration of Independence

On May 14, 1948, the Israeli Declaration of Independence’s ceremony was held in the Tel Aviv Museum (today known as Independence Hall) on Rothschild Boulevard in the city center. But it was not widely publicized, since the Jews feared that the British Authorities might attempt to prevent it, or that the Arab armies might invade earlier than expected.

An invitation was sent out by messenger on the morning of May 14th, telling recipients to arrive at 15:30 (3:30 pm) and to keep the event a secret. The event started at 16:00 (4:00 pm) — a time chosen so as not to breach Shabbat — and was broadcast live as the first transmission of the new radio station, Kol Yisrael.

The declaration’s final draft was typed at the Jewish National Fund building, also in Tel Aviv, following its approval earlier in the day. Israeli politician Ze’ev Sherf, who stayed at the building in order to deliver the text, had forgotten to arrange transport for himself, so he flagged down a passing car and asked the driver (who was driving a borrowed car without a license) to take him to the ceremony. While driving across the city, they were stopped by a police officer for speeding, though a ticket was not issued, since they explained that he was delaying the declaration of independence.

Sherf arrived at the museum at 15:59 (3:59 pm). At 16:00 (4:00 pm), Ben-Gurion opened the ceremony by banging his gavel on the table, prompting a spontaneous rendition of Hatikvah, soon-to-be Israel’s national anthem, from the 250 guests. On the wall behind the podium hung a picture of Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, and two flags, later to become Israel’s official flag.

After telling the audience, “I shall now read to you the scroll of the Establishment of the State, which has passed its first reading by the National Council,” Ben-Gurion proceeded to read out the declaration, taking 16 minutes, ending with the words, “Let us accept the Foundation Scroll of the Jewish State by rising” and then called on Rabbi Yehuda Leib Fishman (who became Israel’s first Minister of Religions) to recite the Shehecheyanu blessing.

As such, Tel Aviv was the temporary government center of the State of Israel until the government moved to Jerusalem in December 1949. Due to the international dispute over the status of Jerusalem, most embassies remained in or near Tel Aviv.

Growth Spurts

The boundaries of Tel Aviv and Jaffa became a matter of contention between the Tel Aviv municipality and the Israeli government in 1948. The former wished to incorporate only the northern Jewish suburbs of Jaffa, while the latter wanted a more complete unification.

In 1949, the government voted on the unification between Tel Aviv and Jaffa. The name of the unified city was Tel Aviv until August 1950, when it was renamed Tel Aviv-Jaffa in order to preserve the historical name Jaffa.

In the 1960s, some of the older buildings were demolished, making way for the country’s first high-rises. The historic Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium was controversially demolished, to make way for the Shalom Meir Tower, which was completed in 1965, and remained Israel’s tallest building until 1999. Tel Aviv’s population peaked in the early 1960s at 390,000 — representing 16-percent of the country’s total.

By the early 1970s, Tel Aviv had entered a long and steady period of continuous population decline, which was accompanied by urban decay. And by 1981, Tel Aviv had entered not just natural population decline, but an absolute population decline as well.

Construction activity had moved away from the inner ring of Tel Aviv, to its outer perimeter and adjoining cities, where better housing conditions were available. Plus, cramped housing conditions and high property prices pushed families out of Tel Aviv and deterred young people from moving in.

In the 1970s, the apparent sense of Tel Aviv’s urban decline became a theme in the work of novelists such as Yaakov Shabtai. A symptomatic article in 1980 asked, “Is Tel Aviv Dying?” and portrayed what it saw as the city’s existential problems:

“Residents leaving the city, businesses penetrating into residential areas, economic and social gaps, deteriorating neighborhoods, contaminated air — Is the First Hebrew City destined for a slow death? Will it become a ghost town?”

By the late 1980s, attitudes toward the city’s future had become markedly more optimistic. It had also transformed into a center of nightlife and discotheques for Israelis who lived in the suburbs and adjoining cities. By 1989, Tel Aviv had acquired the nickname “Nonstop City,” a reflection of the growing recognition of its nightlife and 24/7 lifestyle, and “Nonstop City” had to some extent replaced the former moniker, “First Hebrew City.”

In the 1990s, Tel Aviv’s population decline started to reverse and stabilize, at first temporarily due to a wave of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Tel Aviv absorbed more than 40,000 such immigrants, many educated in scientific, technological, medical, and mathematical fields. During this period, the number of engineers in the city doubled, and Tel Aviv began to emerge as a global hi-tech center.

In 1993, Tel Aviv was categorized as a world city. However, the city’s municipality struggled to cope with an influx of new immigrants. Tel Aviv’s tax base had been shrinking for several years, as a result of its preceding long-term population decline, which meant there was little money available to invest in the city’s deteriorating infrastructure and housing.

In 1998, Tel Aviv was on the “verge of bankruptcy,” according to current mayor, Ron Huldai. (Huldai has become the city’s longest-serving mayor, exceeding Shlomo Lahat’s 19-year term. Like all other mayors in Israel, no term limits exist for the Mayor of Tel Aviv.)

Economic difficulties were then compounded by a wave of Palestinian suicide bombings across the city from the mid-1990s to the end of the Second Intifada, as well as the dot-com bubble, which affected the city’s rapidly growing hi-tech sector.

On November 4, 1995, Israel’s prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, was assassinated at a Tel Aviv rally in support of the Oslo Accords, potential agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The outdoor plaza where this occurred, formerly known as Kings of Israel Square, was renamed Rabin Square — which is home to the Tel Aviv City Hall, and is Israel’s largest square.

New laws were introduced to protect Modernist buildings, and efforts to preserve them were aided by UNESCO recognition of Tel Aviv’s White City as a world heritage site in 2003. In the early 2000s, the Tel Aviv municipality focused on attracting more young residents by making significant investment in major boulevards, to create attractive pedestrian corridors. Former industrial areas, like the city’s previously derelict Northern Tel Aviv Port and the Jaffa railway station, were upgraded and transformed into leisure areas.

As a result, the city’s demographic profile changed in the 2000s; by 2012, 28-percent of the city’s population was aged between 20 and 34 years old, which transformed Tel Aviv’s finances, and by 2012 it was running a budget surplus.

A Future City

Although founded in 1909 as a small settlement on the sand dunes north of Jaffa, Tel Aviv was envisaged as a future city from the start. Its founders hoped that, in contrast to what they perceived as the squalid and unsanitary conditions of neighboring Arab towns, Tel Aviv was to be a clean and modern city, inspired by the European cities of Warsaw and Odessa.

Nowadays, what makes Tel Aviv vastly different than its counterparts — i.e. New York City, London, Paris, Shanghai, Sao Paulo — is its modest size: just 52 square kilometers (20 square miles). From east to west, from the inland areas to the Mediterranean Sea, the city is no more than three kilometers (less than two miles) wide. And from north to south, Tel Aviv is 15 kilometers long (about nine miles). Still, an average of one million people go in and out of the city on a daily basis, in addition to its roughly half-a-million residents.

In 2021, it had the world’s 64th highest GDP per capita of any city, despite boasting the smallest population among these 64 cities. (The next-closest city has approximately 150,000 more people, about one-third of Tel Aviv’s population.)

The city has been ranked second on a list of top places to found a hi-tech startup, just behind Silicon Valley, as well as the second-most innovative city in the world, behind Medellín and ahead of New York City.

Tel Aviv has also been ranked as the world’s 25th-most important financial center, and receives the fifth-most amount of international visitors of any city annually across the Middle East and Africa. (Ben-Gurion Airport, not in but near Tel Aviv, was named a finalist among the category of Best Customer Service in the 2022 Global Travel Retail Awards.)

The city is home to:

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) headquarters, known in Hebrew as HaKirya

Tel Aviv University, the largest university in Israel, known internationally for its physics, computer science, chemistry, linguistics, and film departments

The Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE), Israel’s only stock exchange, which has reached record heights since the 1990s and has also gained attention for its resilience and ability to recover from wars and disasters

544 active synagogues, including historic buildings such as the Great Synagogue, established in the 1930s

Park HaYarkon, which is slightly larger than Central Park in New York, and double the size of Hyde Park in London (Tel Aviv is ranked as the greenest city in Israel.)

13 beaches, hence why Tel Aviv has been ranked as one of the top 10 oceanfront cities

Tel Aviv Fashion Week, which in part has propelled Tel Aviv to be “next hot destination” for fashion

Maccabi Tel Aviv Basketball Club, a world-known professional team, which holds 55 Israeli titles, has won 45 editions of the Israel cup, and has six European Championships; and Maccabi Tel Aviv Football Club, which has won 23 Israeli league titles, 24 State Cups, seven Toto Cups, and two Asian Club Championships

Eight methods of transportation, including buses, railway, bikes, scooters, personal car-sharing services, taxis, service taxis (ride-sharing taxis), and the hybrid overground/underground light rail (currently under construction)

The outdoor Carmel Market, established in the 1920s, which Time Out called “the pulsating heart of the city”

In addition, Tel Aviv is home to three of the most prominent museums in Israel:

Tel Aviv Museum of Art, dedicated to the preservation and display of modern and contemporary art from Israel and around the world

Eretz Israel Museum, known for its collection of archaeology and history exhibits dealing with the Land of Israel

ANU – Museum of the Jewish People, the largest and most comprehensive Jewish museum in the world

In 2015, the Tel Aviv-based Pastel restaurant placed first in the Best Design of Dining Space category, by the International Space Design Award – Idea Tops. And the popular Tel Aviv bar Kuli Alma, which means “All the World” in Aramaic, has been named among the best nightlife joints in the world, thanks to its combination of music and dance, design, revolving art installations, indoor/outdoor accommodations, and pizza.

In 2016, the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network (GaWC) at Loughborough University reissued an inventory of world cities based on their level of advanced producer services. Tel Aviv was ranked as an alpha-world city, a primary node in the global economic network. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that, compared with Westernized cities, crime in Tel Aviv is relatively low.

And the food. Oh, the food! With more than 4,000 restaurants, this culinary capital has it all: fine dining to street food, Middle Eastern to Asian fusion, and beyond. Plus, Tel Aviv comprises more than 100 sushi restaurants, making it the world’s third-highest concentration of such restaurants.

In the last decade, the city has been attracting leading hotel brands like the Mandarin Oriental, Kempinski, The W, and Nobu Hotels. Not to mention, the literally hundreds of boutique hotels, including The Norman Hotel, which has been voted among the world’s 50 best hotels (and first in the Middle East category).

And, arts and entertainment are booming: Eighteen of Israel’s 35 major performing arts centers are located in Tel Aviv, including five of the country’s nine large theaters, where 55-percent of all performances in the country and 75-percent of all attendance occurs. The Israeli Ballet is also based in Tel Aviv.

Certainly, all of these accomplishments come with a ballooning price tag: In 2021, Tel Aviv became the world’s most expensive city to live in, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit.

But when you think about the period of time that Tel Aviv has been a “major city” (less than 100 years), its relatively humble geographic size, and the amount of residents it houses (less than a half-million), it’s easy to understand how Tel Aviv is Israel’s best invention. And, perhaps, the greatest city — pound-for-pound — in the world.

The end.

Zehorai, Itay. “Israel is among the top 20 global economies in GDP per capita for the first time.” Forbes. May 5, 2021, https://forbes.co.il/e/israel-is-among-the-top-20-global-economies-in-gdp-per-capita-for-the-first-time.

“General view of the Israeli dairy farming.” Israel Dairy Board. https://www.israeldairy.com/general-view-israeli-dairy-farming.

“25 Things You Should Know About Tel Aviv.” Israel Consulate General of Israel in Los Angeles. January 22, 2016, https://embassies.gov.il/la/NewsAndEvents/Pages/25-Things-You-Should-Know-About-Tel-Aviv.aspx.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Israel at 71.” ISRAEL21c. May 7, 2019, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-celebrates-71-a-statistical-snapshot-of-a-remarkable-country.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Israel at 71.” ISRAEL21c. May 7, 2019, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-celebrates-71-a-statistical-snapshot-of-a-remarkable-country.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Israel at 71.” ISRAEL21c. May 7, 2019, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-celebrates-71-a-statistical-snapshot-of-a-remarkable-country.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Israel at 71.” ISRAEL21c. May 7, 2019, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-celebrates-71-a-statistical-snapshot-of-a-remarkable-country.

Eyal Boers, Chairman - The Israel Film Council.

Spiro, James. “A deep dive into Israeli tech’s record-breaking year.” Calcalist Ctech. January 23, 2022, https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/articles/0,7340,L-3927712,00.html.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Israel at 71.” ISRAEL21c. May 7, 2019, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-celebrates-71-a-statistical-snapshot-of-a-remarkable-country.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Israel at 71.” ISRAEL21c. May 7, 2019, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-celebrates-71-a-statistical-snapshot-of-a-remarkable-country.

Hodgson, Leah. “Singapore tops list in VC funding per capita.” PitchBook. June 1, 2022, https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/vc-funding-per-capita-singapore-israel-united-states.

Leichman, Abigail Klein. “Israel ranks as world’s third most educated country.” ISRAEL21c. December 20, 2018, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-ranks-as-worlds-third-most-educated-country.

“Everything you ever wanted to know about Israel at 71.” ISRAEL21c. May 7, 2019, https://www.israel21c.org/israel-celebrates-71-a-statistical-snapshot-of-a-remarkable-country.

“Tel Aviv.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tel_Aviv.

“Old New Land: The Story Behind the First Photograph of the Founding of Tel Aviv, 1909.” Vintage Everyday. May 12, 2018, https://www.vintag.es/2018/05/founding-of-tel-aviv-1909.html.