The Jewish world needs a Bad Bunny.

Jewish culture won’t survive on fear, funding decks, and talking points alone.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Every culture that survives does more than preserve itself.

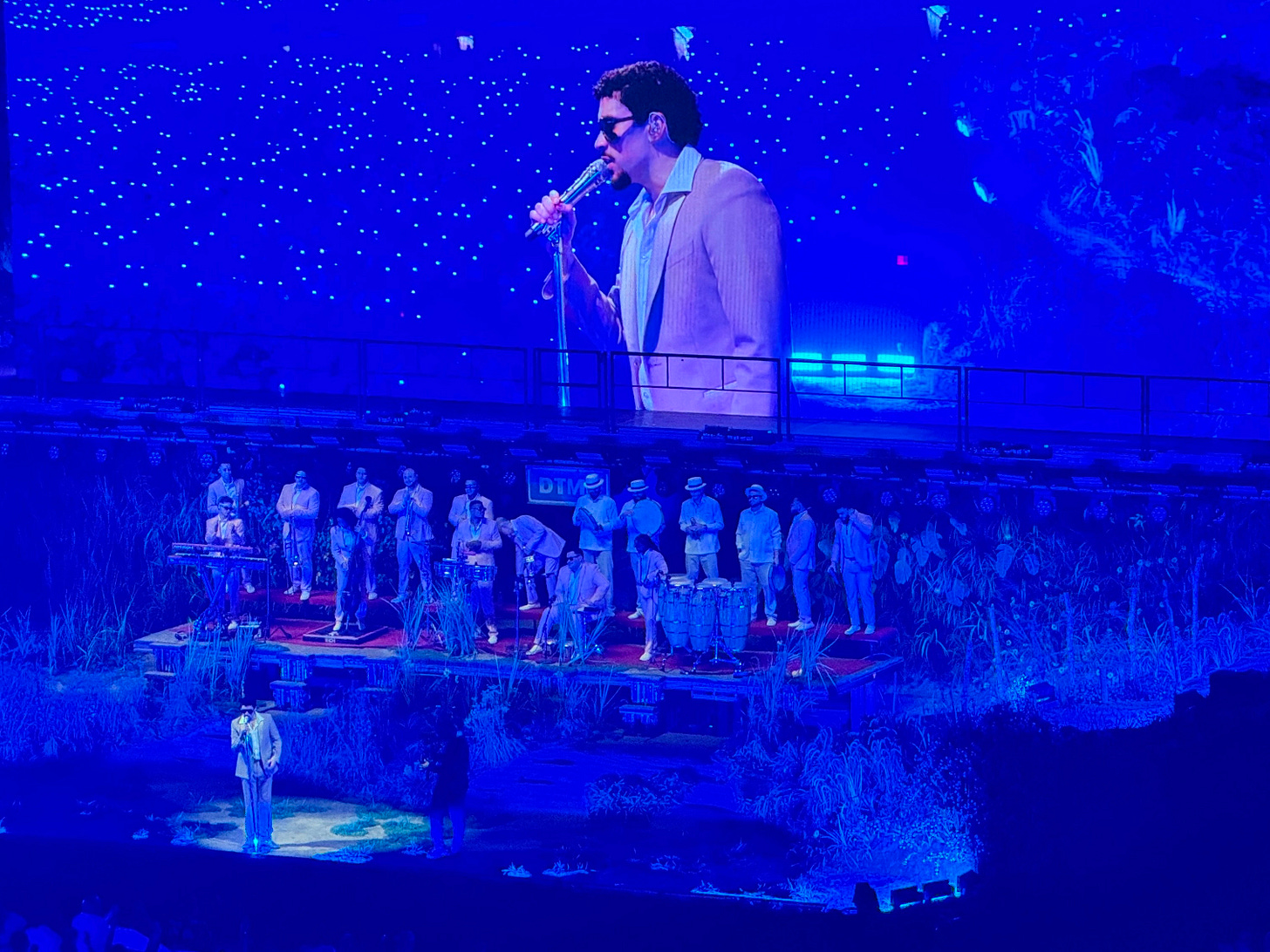

It reinvents itself. It finds new language, new sound, new icons that translate old identity into something that feels alive right now. That’s what reggaeton did for Puerto Rican culture. That’s what K-pop did for South Korea. That’s what Super Bowl halftime performer Bad Bunny just did on Sunday.

The Jewish world desperately needs its own Bad Bunny.

Not a novelty act. Not a niche “Jewish artist.” Not someone whose Judaism is a fun biographical footnote. But a cultural force who makes Jewishness feel confident, cool, modern, and unavoidable — someone who can re-enchant young Jews and, just as importantly, pull non-Jews in rather than explain ourselves to them.

Right now, Jewish culture is surviving. It is not conquering.

Yes, Jewish musicians exist. Many of them are enormous stars. But their Jewishness is incidental to their art, not central to it. Pink, Adam Levine, Drake — they are Jewish people making music, not Jewish music reshaping culture. Their work does not transmit Jewish identity; it politely sets it aside.

Jewish artists today are often praised for representation — “Look, a Jew succeeded!” — but representation is not cultural ownership. It’s permission-based. Ownership is when the culture moves on Jewish terms, without translation. Bad Bunny doesn’t represent Puerto Ricans to the world. He forces the world to enter Puerto Rican space. Jewish culture, by contrast, is constantly stepping outside itself to be understood.

And that distinction matters.

When Bad Bunny sings, you feel Puerto Rico even if you don’t speak Spanish. When BTS performs, you feel Korea even if you’ve never been there. Culture, when done right, does not ask permission. It asserts itself. Jewish culture already contains Hebrew and English, prayer and irony, exile and confidence. What it lacks is not material; it lacks permission.

Israel, in theory, should be the engine of Jewish cultural export. In practice, it isn’t.

Top Israeli artists dominate locally but fail to translate internationally. Omer Adam is a phenomenon in Israel and almost invisible outside it. The late Arik Einstein was foundational to Israeli identity, but utterly non-exportable. Mergi has talent and charisma, yet remains culturally bounded.

Even artists who try to bridge the gap by singing in English struggle. Noa Kirel is polished, ambitious, and globally oriented — but still hasn’t broken through in a meaningful way. Full Trunk has groove and soul but remains niche. Netta Barzilai briefly captured global attention, but novelty proved easier to export than cultural gravity. Dennis Lloyd has come closest, earning critical respect abroad, yet still hasn’t crossed into true cultural centrality.

This isn’t a talent problem. It’s a cultural positioning problem.

Jewish music today is either hyper-universal (so universal that it loses its Jewish distinctiveness) or hyper-particular (so inward-facing that it can’t travel). The result is a vacuum where Jewish confidence should be.

A Jewish Bad Bunny wouldn’t dilute Jewishness to be palatable. They would intensify it. They would treat Jewish symbols, language, rhythms, humor, and history not as explanations but as raw material. Hebrew wouldn’t be a barrier; it would be a flex. Jewish themes wouldn’t be apologetic; they would be magnetic.

This matters far beyond music.

Young Jews are not rejecting Judaism because they hate it. They are drifting because it feels brittle, defensive, or frozen in time. Culture is how identity breathes. When culture stagnates, identity becomes a burden instead of a source of pride.

And non-Jews? They don’t need Jewish culture to be translated for them. They need it to be compelling. Nobody asks Bad Bunny to explain Puerto Rican politics before dancing. Nobody requires footnotes to feel the confidence of Korean pop. Attraction precedes understanding.

The Jewish world has spent decades investing in education, advocacy, and defense — all important, necessary work. But it has underinvested in cultural dominance. In joy. In swagger. In art that says: We are here, we are alive, and we are not shrinking.

What makes this cultural vacuum even more glaring is where Jewish money actually goes. Jewish donors today are overwhelmingly obsessed with “combatting antisemitism.” Not Jewish culture. Not Jewish confidence. Not Jewish creativity. Antisemitism. And Jewish organizations have learned to prey on this fixation with remarkable efficiency. Fear raises money faster than beauty. Crisis outperforms confidence. Defensive postures are easier to justify than ambitious ones.

The result is an ecosystem of organizations, each operating according to its own insulated logic, producing reports, campaigns, conferences, and toolkits that speak almost exclusively to one another. Metrics are internal. Impact is abstract. Success is measured in dollars raised and statements issued, not in whether Jewish life feels more compelling, joyful, or alive a decade later. The real tragedy, then, is not that the Jewish world lacks talent; it’s that it lacks a cultural ecosystem willing to let talent, creativity, and a little chutzpah do the talking.

Meanwhile, the cultural front — the place where identity is actually formed and transmitted — remains underfunded and under-imagined. You cannot defensive-campaign your way into a renaissance. You cannot workshop your way into cool. And you certainly cannot inoculate a generation against antisemitism by teaching them that being Jewish is something that must constantly be explained, justified, or protected by institutions rather than expressed through power and presence.

Bad Bunny did not emerge from a foundation grant designed to “combat anti-Puerto Rican sentiment.” K-pop was not born out of a conference on “countering Korean stereotypes.” Culture does not grow out of fear; it grows out of confidence and creative risk. Yet Jewish institutions continue to behave as if the central question of Jewish continuity is how Jews are treated by others, rather than how Jews see themselves.

This obsession with antisemitism has produced a strange inversion: Jewish life is framed as perpetually under siege, while Jewish culture is treated as a luxury item — nice if there’s money left over after the emergency.

After October 7th, the Jewish world doubled down on defense, messaging, and emergency fundraising. Understandably. But emergencies calcify instincts. And a people that lives forever in emergency mode does not produce great culture; it produces compliance and exhaustion. For young Jews especially (but not only), that framing is suffocating. No one wants to inherit an identity defined primarily by threat management.

A Jewish Bad Bunny would not solve antisemitism. That’s not the point. They would solve something more internal and just as urgent: the sense that Jewishness belongs to the past or exists only under threat. They would not fit neatly into any existing institutional category. They would not be an “initiative.” They would not align cleanly with a donor strategy deck. And that is precisely the point: Cultural breakthroughs rarely emerge from risk-averse systems optimized to preserve themselves.

If the Jewish world wants a future that feels expansive rather than defensive, it will have to loosen its grip on fear as the organizing principle of Jewish life and start investing in culture as power, not ornament. Because the most effective way to combat antisemitism has never been to chase it; it has been to build something so alive, confident, and magnetic that Jewishness itself becomes impossible to dismiss.

That kind of cultural confidence does not emerge from consensus or committee. Every renaissance begins with audacity — with someone willing to be unmistakably themselves and daring the world to keep up. The Jewish world doesn’t need better talking points; it needs a beat it can’t ignore.

And that beat may not even come through music. A Jewish Bad Bunny could emerge from fashion, film, digital culture, comedy, or from a form that doesn’t yet exist. What matters is not the medium but the posture: unapologetic, untranslatable, and contagious.

I'm sure you're right to argue that the Jewish world would benefit from more well known performers, but Bad Bunny (I don't think) should be held up as the example to imitate. His fame (or rather infamy) right now derives from offending millions Americans at an iconic American ritual, the Superbowl. His lyrics are pornographic and just plain stupid. As far as I can tell, he is being used to ideologically subvert and internally weaken the USA by undermining its traditions. He is not a positive role model. Prior to his sports event, I had never heard of him, and now I wish I hadn't.

That having been said, there are many great Jewish thinkers, artists, composers, comedians, and films -- too many to list -- that the world would do well to read, listen to, or watch.

Nobody needs a bad ffing bunny, but England needs an IDF