The road to Jewish hell is paved with 'Tikkun Olam.'

What is it about this popularized Hebrew phrase that seems to drive people batsh*t crazy and leads us to disaster?

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay written by Sam Hilt, author of the book, “Paradigm Wars: A Brief History of Consciousness from the Insects to the Antisemites.”

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

If there’s still anyone out there who is not familiar with the Hebrew phrase, “Tikkun Olam,” a literal translation would be: “repairing the world.”

Simple enough.

In fact, it’s so short and sweet that it has become one of the most popular ways that modern secular Jews explain to non-Jewish friends and colleagues what Judaism is all about: “Tikkun Olam means doing your part to make the world a better place for everyone.”

What’s not to like? Who wouldn’t want to sign up for religion like this? Isn’t that really what we’re all pursuing through all the world’s different religions?

If this strikes you as an oversimplification, you are absolutely right. More about that in a minute, but first let’s consider a couple of the peculiarities that surround the outsized popularity today of the phrase “Tikkun Olam.”

In ancient Israel, in the first centuries of the Common Era, the phrase “Tikkun Olam” already appeared in the Jewish liturgy in the Amidah prayer1 which was recited at each of the three daily prayer services. The prayer affirmed the hope of “the repair of the world under the Kingdom of God” — but without elaboration.

“Tikkun Olam” went on to play a very minor role in Talmudic jurisprudence during the Middle Ages, and it wasn’t until the late 13th century in Spain that we see the first inklings of its current usage. It was here in the medieval Jewish community in Castille that a mystical text known as the Zohar appeared.

A Rabbi named Moses de Leon claimed that he had discovered a manuscript which preserved the teachings of an ancient sage, Simeon ben Yochai, who had lived toward the end of the first century CE.

And it was this text of dubious provenance which presented the idea that the world was flawed and that humanity was challenged to repair the cosmic balance. It would be hard to invent a more obscure origin for what became the banner phrase for contemporary social justice warriors, but there you have it.

Fast forward to the 16th century, when a major development of this notion of repairing a flawed world took place through the writings of the Kabbalist, Isaac Luria. At this point, “Tikkun Olam” was embedded into a cosmogonic epic which discussed the creation of the universe and the origins of the problem of evil.

Anyone who begins to study Kabbalah soon learns the strange story of the flasks that burst asunder as they were being filled with Divine Light which they were too fragile to contain. After this disastrous explosion during the act of Creation, the world we live in became a mish-mash of light and dark, of spirit and matter, of good and evil.

And the task of the righteous soul was to redeem the sparks of Divine Light scattered throughout the material world by means of personal spiritual development: fasting, prayer, and contemplative exercises.

Now, here’s where the plot thickens: When you begin with a core belief in the imperfection of the world, and the possibility of the human soul to perfect itself, it’s only a matter of time until the quest for self-improvement turns toward the world and asks, “How can we make the world a better place?”

By the 17th century, this impulse sought first and foremost to transform the precarious situation of the Jewish People. It was a period when Kabbalistic thought became a mainstream current of Judaism, and the redemption of the Jewish People appeared to be at hand. A spiritual leader by the name of Sabbatai Zevi declared himself to be the Messiah, and he even undertook a journey to Istanbul, where he implored the Sultan to convert to Judaism. It didn’t go too well for him.

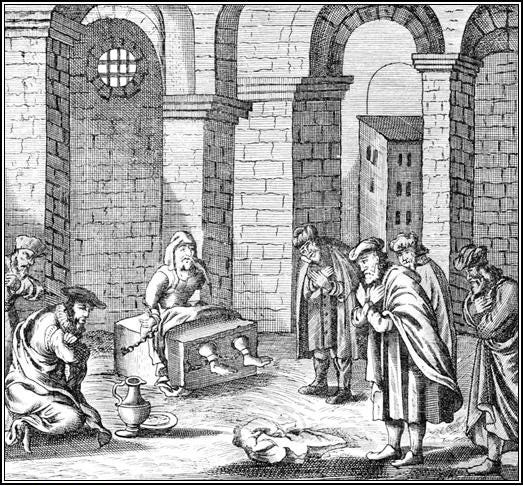

After being cast in irons and imprisoned in the Sultan’s dungeon, Sabbatai Zevi was given the choice of converting to Islam or having his head cut off. He chose the former option and left the Jewish world to puzzle over how it could have been so thoroughly misled by a false Messiah. Kabbalistic Judaism was fatally discredited and marginalized for centuries, and the rationalist currents of Rabbinic Judaism won the day.

Meanwhile, in another part of town…

The pattern of outsized transcendent aspirations succeeded by flamboyant disasters was not limited to the Jewish world of that time and place. In Renaissance Florence in the 15th century, for example, under entirely different circumstances, a strangely similar story unfolded.

Like the Spanish Kabbalists on the Iberian peninsula, the protagonists of the early Florentine Renaissance engaged in the search for esoteric knowledge about the nature of the soul, life after death, and the destiny of mankind. Under the patronage of the ruling Medici family, the Platonic Academy of Florence was established and artists like Botticelli and Michelangelo flourished.

At about the same time, through an ambitious program of fresco painting, the monastic artist, Fra Angelico, transformed the monastery of San Marco in Florence into a sort of mystery school. Every monk’s cell was provided with a wall-sized painting depicting a Biblical scene.

Newly arrived, the novitiates were introduced to esoteric dimensions of Christianity through the active contemplation of religious imagery. Church and State coexisted happily and productively until Girolamo Savonarola, the new rector of San Marco monastery, decided to take things to the next level.

Savonarola embarked on a campaign to bring moral improvement to the people of Florence. A charismatic preacher with a gift for prophecy, he drew large crowds and had a loyal following, especially among the youth. At his rallies, known today as the “Bonfires of the Vanities,” people were encouraged to throw their superfluous luxury goods into the flames.

Precursors of Mao’s Red Guards, bands of youths accosted private citizens and constrained them to toss their jewels and furs into the bonfires. Even Botticelli was swept up in the spiritual frenzies and burned some of his own paintings which treated non-Christian themes. In the end, after a couple of failed predictions doused the flames of Savonarola’s popularity, he was arrested, imprisoned, and then burned at the stake in Florence’s main square.

It's fascinating and disturbing to step back and consider how many well-intentioned efforts to inaugurate the kingdom of heaven here on earth have ended in disaster. In the Jewish tradition, the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel serves as a cautionary tale that would discourage us from attempting to get too close to heaven. It ends with all the workmen babbling in different languages and throwing bricks at one another.

Elsewhere, comparable ambitious efforts led to much bloodier results. For example, during the French Revolution, the Gregorian calendar was discarded, all the months were renamed, and the year was reset from 1793 to zero.

With a brand new beginning, a fresh start, the Committee for Public Safety under the able leadership of Maximilien Robespierre was able to identify and execute more than 17,000 enemies of the Republic in less than a single calendar year. Despite his stellar efforts to make the world a better place, an ungrateful government faction sent Robespierre himself to the guillotine the following year.

It would be an understatement to say that the French Revolution was not an unqualified success. Nevertheless, it has continued through these intervening centuries to serve as an example of the relentless human drive to create a more perfect world.

After the astonishing, creative ferment of 19th-century Russian society in the fields of literature, music, and painting, after all the salon discussions of how to create a more just society, after the anarchists and the nihilists and all the political manifestos, the Bolsheviks maneuvered their way to the position of top dog. They executed the Czar and his whole family, eliminated all their political rivals, and orchestrated the mass starvation of millions of Russian peasants to preempt their potential to interfere with government policies.

In Russia, Lenin and Stalin killed their millions while, in China, Mao Zedong killed tens of millions more than even they could manage.

Although Stalin and Mao are the undisputed record holders for mass murder in the service of social improvement, many others have been inspired by similar ideals even when their efforts took different forms. Adolf Hitler aspired to restore the pride of a defeated nation by marginalizing and then exterminating the Jews and other inferior racial groups who might degrade the pure blood of the noble German people.

Pol Pot in Cambodia adopted a different strategy in his quest for purity: He surmised that all those who wore glasses had been corrupted by at least some formal education, so he had them all escorted to the killing fields.

All of which invites the following reflection: These movements always begin with the goal of making the world a better place. Despite high hopes and initial promising results, the road always seems to lead to psychological derangement, chaos, and death.

So, what is it about “Tikkun Olam” — the dream of improving life on earth — that seems to drive people batsh*t crazy and leads us to disaster?

Let me try to grope my way toward a tentative answer, by recalling my own excitement and enthusiasm when I was first introduced to certain elements of Marxist thought. One of the most compelling ideas that I encountered was the notion of the power of “Negative Reason.” This construct invited you to recognize that the world around you was merely reality as it currently exists. And that we have the ability to negate that which is as we imagine and build that which can be.

There was something profoundly exhilarating in the realization that the world around us was like a still from a movie, the image of a moment in the unfolding story of society in our time. And with this insight came the realization that we were actors in this movie who could intervene and direct it towards the achievement of great ends.

Wow, what a thrill that was for a 19-year-old aspiring radical intellectual! As I observed normal people just going about their lives it seemed to me that they were just sleepwalkers. They were the “Muggles,” and we were the students who had been shown the hidden track and were eager to board the next train to “Hogwarts.”

After the period of “awakening” to a higher calling, next came the solicitations to action: All aboard! Don’t miss your chance to be a part of a select group that is working to make the world a better place. There’s so much suffering in the world: inequality, exploitation, injustice. You can’t just sit around while others are being oppressed. Call 1-800-End-Evil and donate your time and money to save the oppressed people of Victimlandia!

We are long past the naïve period when leaders arose spontaneously out of oppressive circumstances and groups formed around them. Today it’s apparent that the entire process from recruitment through deployment has been studied and polished to near perfection. The Egyptian-Italian journalist and politician, Magdi Allam, coined the phrase “the kamikaze assembly line” to describe the process developed by the Muslim Brotherhood through which young madrassa2 students were gradually but inexorably transformed into suicide bombers.

We would like to believe that there exists a vast, nearly unbridgeable distance between the illiterate children of peasants in rural Afghanistan and the sophisticated kids of New York professionals. But the facts suggest otherwise.

After the Hamas-led massacre of October 7th, the young Jewish students who participated in “solidarity encampments” at Ivy League universities in support of Hamas demonstrated that their moral compass and their survival instincts could be easily subverted. The lure of linking arms with others to stand (or sit) against injustice and oppression, to help make the world a better place, was too strong to resist.

And, so, they proudly shouted the genocidal chant “From the River to the Sea” and joined the ranks of assorted useful idiots along with “Gays for Gaza” and “Chickens for KFC.”

“I’m all about Tikkun Olam! Just wind me up, point me in the direction of social justice, and I will walk off the cliff and virtue signal all the way down.”

It’s well worth noting that observant Jews and practicing Christians were not so easily seduced like their more secular brethren. It was the well-healed, “progressive,” so-called college-educated crowd that stood ready to throw Jews, Israel, and conservatives under the bus in their service to a higher, nobler ideal.

We are forced to ask: What is it that makes secular, educated people who want to make the world a better place such easy marks for the wicked forces that would destroy them and everything else around us?

Hint: The dark side of “Tikkun Olam” is hidden in plain sight. The danger that lurks in the perilous quest to repair a broken world is inherent in its point of departure.

We are constrained to begin from a critical stance; that is, what’s wrong with this picture? We are directed to focus all our attention on what needs to be fixed, changed, removed, destroyed. And we are exalted and inflated through our own self-selection as change-agents who are making the world a better place.

Meanwhile, there is not a whit of reverence for what is. There’s no appreciation whatsoever for the world that we’ve been born into, for the arduous and often perilous labors of all those who came before us to build what we have inherited, for those who fought with courage and those who gave their lives to secure the freedom and liberties we enjoy, for the generations of musicians, writers and artists who created the works of genius that light our lives, for this amazing, green growing earth spinning through the millennia and inviting us to open our eyes and stop the chatter in our minds for just long enough to be humbled and shout “Glory!”

Great art and spiritual practice share the common goal of inviting us to truly see and appreciate the world. They support the grounding function of religion to keep us sane and a bit humble. Jewish ritual is filled with daily prayers of gratitude for the bread we eat, the wine we drink, the peace and health that we enjoy, and the tradition that sustains us.

When we discard the burden of traditional ritual practice without putting some other deep-water anchor in its place, we risk throwing out the baby with the bathwater. We become weightless. And easily led. Pushovers.

“Tikkun Olam” on its own becomes a rootless tree that is hardly distinguishable from “Woke” Marxism — and yields no better fruit. That’s when the commissar who lacks all generosity of soul steps forth from where he’s been waiting and leads the sheep like a Judas goat to the killing floor while they bleat, “From the River to the Sea!”

When Judaism is reduced to “Tikkun Olam,” we can join with others near and far who also subscribe to the universalist dream of making the world a better place. We can share interfaith prayer breakfasts, march together for worthy causes, donate money to alleviate suffering in distant lands. We can free ourselves from the myopic vision of concern with our own well-being, with our own ethnicity, with our own actual history and our national aspirations.

All we have to give up to join the antisemitic, universalist choir is our self-respect, our decency, and our own identity as Jews.

The Amidah, also known as the Shemoneh Esrei or “Standing Prayer,” is the central prayer in Jewish liturgy. It is a series of blessings recited while standing, making it a key part of daily Jewish worship.

An Arabic word that generally refers to a type of educational institution, often a religious school, particularly in the context of Islam

Excellent essay. There is much to be appreciated about the world given us by G-d, and hubris to think we were created by Hashem to repair a broken world, a world created by G-d. The best parts of Kabbalah teach that even the wisest of men can only understand no more than 3% of the world. We should remain humble, work with the tools, intelligence, and spiritual awareness given by Hashem, and repair ourselves and our own creations, the world needs no repairing.

It's true that gratitude for what is, is essential and a counterbalance to seeing what is broken. The problem is not the latter. The former by itself is also problematic when things are going downhill and we don't see it, or pretend not to. That was the story of Pangloss in Voltaire's Candide. Also, wanting to fix things requires both study and humility, so smaller changes in complex systems are more likely to succeed than radical big changes. And gratitude for what is, often is on the shoulders of those before us who also were able to improve things, by seeing what needs to be changed BECAUSE it was broken. The disasters of Stalinism, Maoism and Fascism were due to arrogance, improper understanding of root causes, and (to use J. Peterson's term) ideological possession which takes away compassion, humility and open-mindedness. Those who can't even fix a car, should not attempt to fix a whole society.