This Holocaust survivor turned creativity into an act of resistance.

From forging documents to creating films, Joseph Bau’s ingenuity turned survival into a statement of hope.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay by Lee Tanenbaum, a writer based in the United States.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

I first visited the Joseph Bau Museum in March 2024 during a volunteer trip to Israel. I expected to learn about art and history; instead, I found family.

Joseph Bau’s daughters, Clila and Hadasa Bau, greeted me warmly inside their father’s former studio in Tel Aviv. They quickly noticed my last name and laughed — their mother Rebecca Bau’s maiden name was also Tennenbaum — declaring that I must be a long-lost cousin. That moment of humor and connection set the tone for everything that followed.

Surrounded by Joseph Bau’s original drawings, experimental animation equipment, self-designed Hebrew fonts, poetry, and handmade film projectors, I encountered a story that was deeply human, creative, and defiantly joyful. It was not a conventional Holocaust museum experience; it was alive.

That visit gave new direction to my retirement. For the past 21 months, I have volunteered alongside Clila and Hadasa as a promotion and marketing consultant, helping them sustain and amplify their parents’ extraordinary legacy. In the months since that first visit, I have been privileged to learn more about Joseph Bau: an artist, forger, survivor, humorist, and builder of culture whose creativity was itself a form of resistance.

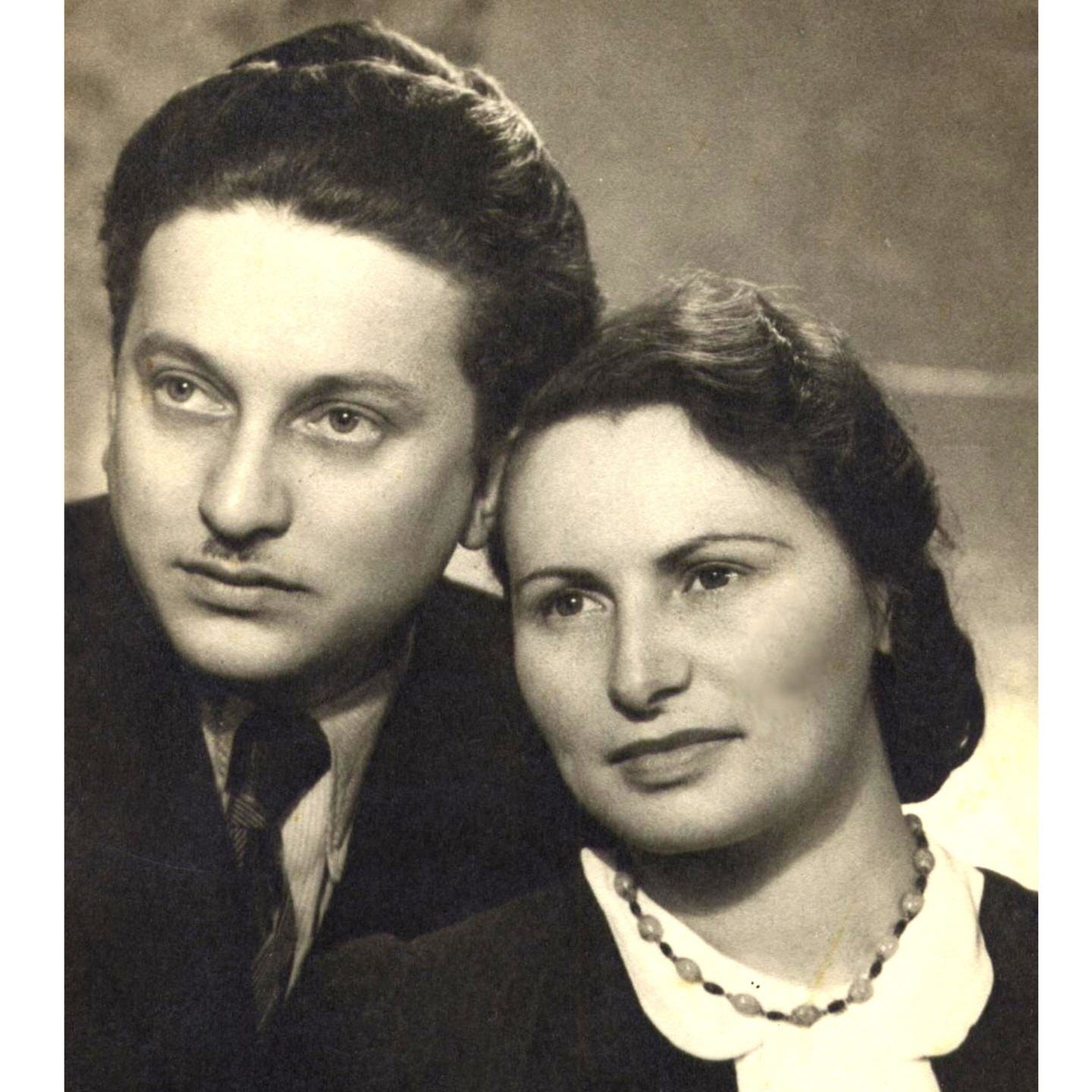

Like many people, I was not initially familiar with Joseph Bau beyond learning (later) that his secret wedding to fellow prisoner Rebecca Tennenbaum held in 1944 inside the Plaszów concentration camp was depicted in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 movie, “Schindler’s List.” With a veil made of scraps, whispered vows, and fellow prisoners standing watch, their whispered vows were an act of defiance against Nazi terror.

But Joseph Bau’s life, and Rebecca’s, cannot be contained in a single cinematic scene, which, powerful as it is, offers only a narrow glimpse of far larger lives.

Before and during his imprisonment, Joseph Bau used his artistic skills to forge documents that saved Jewish lives in the Kraków Ghetto, the Plaszów labor camp, and later at Oskar Schindler’s ammunition factory in Brünnlitz. His talent for typography, forgery, and visual detail became tools of survival.

After the war, Joseph and Rebecca rebuilt their lives in Israel, carrying trauma but also an unshakable commitment to creativity and joy. Joseph emerged as one of Israel’s pioneering animators and graphic artists. Often described as the “Israeli Walt Disney,” he worked as an artist, animator, typographer, poet, satirist, inventor, author, and publisher. Underlying all of his work was a singular belief: Joy itself is an act of resistance.

In 1960, Joseph Bau opened his art studio in Tel Aviv. It became a cultural laboratory — part workshop, part salon, part theater — where humor, design, poetry, and ideas collided. That studio is now the Joseph Bau Museum, preserving not only Bau’s artwork, but his worldview.

Joseph’s creative ingenuity also extended into covert state work. He later produced documents for the Mossad that supported Israel’s capture of high-ranking Nazi official Adolf Eichmann in Argentina, and assisted legendary Israeli spy Eli Cohen infiltrate top levels of the Syrian government from 1961 and 1965. These chapters of his life further illustrate the unusual intersection of art, intelligence, and survival that defined his legacy.

For more than two decades, Clila and Hadasa Bau have managed the Joseph Bau Museum, one of more than 200 officially recognized heritage sites in Israel. Unlike institutional museums, this space remains intimate and deeply personal.

The museum houses what is considered the smallest theater in the world, where visitors watch Bau’s animations and view his original, self-made projection and copying equipment. His humor is everywhere, sometimes gentle, sometimes biting, but always human.

Visitors consistently describe leaving not only informed, but reawakened: reminded of creativity’s power to sustain life even after atrocity. Perhaps that explains why, in 2023 and 2024, TripAdvisor named the Joseph Bau Museum “Best of the Best,” placing it in the top one percent of global attractions and ranking it number one out of 300 things to do in Tel Aviv.

And yet, recognition does not guarantee security.

The building that houses Joseph Bau’s original studio has been sold and is slated for demolition. Without a viable relocation, this singular museum — intimate, original, and irreplaceable — could disappear.

At the very moment the museum’s future has become uncertain, Joseph and Rebecca Bau’s story has reached a global audience through cinema.

I was honored to join Clila and Hadasa at the September 21st premiere of Paramount’s feature film “Bau: Artist at War” at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. Watching their parents’ story unfold on the big screen — survival, espionage, love, humor, and reinvention — was profoundly moving. It underscored why preserving the Joseph Bau Museum matters, not only as a memorial, but as a living testament to creativity, resistance, and moral courage.

At the premiere, Clila and Hadasa walked the red carpet as stewards of a legacy that survived genocide, espionage, war, love, and reinvention — and now must contend with the pressures of modern real estate. The film’s international release has brought renewed global attention to the Bau story at precisely the moment when the museum’s future is most uncertain.

Directed by Sean McNamara, “Bau: Artist at War” was released in the United States and Canada in September 2025 and screened internationally, including recent special screenings in Israel. The film is now available for home viewing via major digital platforms.

The film’s reach has expanded even further. “Bau: Artist at War” is now available to view on Delta, United, and American Airlines flights, introducing Joseph and Rebecca Bau’s story to international travelers around the world.

Emile Hirsch stars as Joseph Bau, delivering a performance that captures Bau’s irreverent wit, moral courage, and creative defiance. Hirsch portrays Bau not simply as a Holocaust survivor, but as a multidimensional artist whose humor and imagination were essential tools of resistance.

Opposite him, Inbar Lavi portrays Rebecca Tennenbaum Bau with quiet strength and emotional depth. Her performance foregrounds Rebecca’s intelligence, resilience, and moral steadiness — qualities that sustained both her and Joseph during and after the war.

The screenplay was written by Deborah Smerecnik, who also served as a producer on the film. Drawing from Joseph Bau’s memoir and extensive historical research, Smerecnik crafted a narrative that balances historical accuracy with emotional intimacy. Her dual role as writer and producer helped ensure that the Bau family’s voice, values, humor, and lived experience remained central to the film’s development.

In a parallel milestone, Joseph Bau’s Holocaust memoir, “Dear God, have you ever gone hungry?” was republished in January 2025 by Blackstone Publishing. The new edition includes a foreword by daughters Clila and Hadasa, offering readers insight into their father’s legacy and voice, an introduction by Sean McNamara, director of the major motion picture of the same name, and an afterword by Inbar Lavi, who portrays Rebecca Bau in the film.

Together, the film and the memoir allow global audiences to encounter Joseph Bau’s story in his own words and through cinematic interpretation, at the very moment the physical space preserving his life’s work is at risk.

Of course, we are living in a time when Holocaust survivors are leaving the world and historical truth is increasingly challenged. The Joseph Bau Museum is not just a repository of artifacts; it is a living expression of how one man, and one family, chose creativity, humor, and love in the aftermath of devastation.

To lose a museum this personal, this joyful, and this defiant would mean losing a rare compass for understanding how art can confront hatred without surrendering humanity. Joseph and Rebecca Bau did not endure the Holocaust only to have their legacy quietly erased by circumstance. They survived to teach us that love can outlast empires, humor can subvert tyranny, and creativity can rebuild what hatred tries to destroy.

Their story is not only history; it is instruction. Preserving it through film, books, and the living space where it was created is a responsibility that extends beyond any one family or institution. It is a reminder that the brightest resistance is not only to survive, but to build, to create, and to love anyway.

Joseph and Rebecca Bau did not simply leave behind history. They left a model for how to carry light forward, even when the world grows dark.

Thanks for this wonderful introduction to this amazing story...

Trailer. https://youtu.be/wKVDF6TicME?si=u5_p7OLVtnGq-WO2