Trees tell beautiful stories about Judaism and Israel.

Today, the Jewish holiday of Tu BiShvat, is a celebration of the profound meaning of trees across Judaism and Israel.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay by Vanessa Berg, who writes about Judaism and Israel.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

“The further we went, the hotter the sun got — and the more rocky and bare, repulsive and dreary the landscape became. … There was hardly a tree or a shrub anywhere. Even the olive and the cactus, those fast friends of a worthless soil, had almost deserted the country.”

In 1867, Mark Twain wrote the above description, part of the chronicle of his visit to the Holy Land, from his best-selling travel book, “The Innocents Abroad.” The writer and humorist was struck by the contrast between the biblical grandeur he expected and the reality of the land at the time: mostly underdeveloped, sparsely populated, and marked by decay after centuries of Ottoman neglect.

Twain was impressed by the sense of history embedded in the landscape. Even though he often mocked the desolate villages and overgrown ruins, he acknowledged that the hills, valleys, and rivers were deeply evocative of the biblical narrative. The land itself seemed to “speak” through its topography, connecting modern travelers to centuries of Jewish, Christian, and historical memory.

Twain noted, almost wistfully, that the land was fertile and could thrive if properly cultivated. While he saw the neglect of forests, swamps, and villages, he also recognized that the soil and climate were rich and promising.

Twain’s descriptions of the Jordan River, the Sea of Galilee, and the surrounding hills occasionally break through his sarcasm. He admired the scenery, noting the stark contrasts of arid deserts and lush valleys, and these observations convey that the land itself holds intrinsic beauty and value.

Even a skeptic like Twain felt the “aura” of the Holy Land. He described sites with a mix of humor and awe, suggesting that there is something timeless and compelling about Israel’s connection to faith, history, and human imagination.

The Torah introduces trees not only as part of the natural world but as central actors in the spiritual and historical narrative of the Jewish People. The first and most famous is the Tree of Knowledge, planted in the Garden of Eden.

Adam and Eve were permitted to eat freely from all trees except this one, which carried the potential for moral awareness and sin. When they ate its fruit, innocence was lost, their eyes were opened, and humanity gained the knowledge of good and evil.

In contrast, the Tree of Life, also in Eden, symbolized eternal life and divine connection. After the transgression, God placed cherubim and a flaming sword to guard it, reminding humanity of the consequences of moral choices and the preciousness of spiritual immortality.

After the Flood, trees again played a critical role in signaling renewal. When Noah sent out a dove to find dry land, it returned carrying an olive leaf, indicating that life had begun to regenerate and that the world could be repopulated. This olive tree became a timeless symbol of peace, continuity, and the restoration of the earth.

Trees continued to appear in patriarchal narratives as spaces of hospitality, moral decision-making, and covenantal connection. Abraham famously hosted three angels under a tree, providing water and shade, symbolizing kindness and divine blessing. Jacob later buried the idols from Shechem under a fruitless tree, intertwining moral action, protection of sacred values, and the sanctity of designated spaces.

Some trees are remembered through names and ritual. Allon Bachuth, where Rebecca’s nurse Deborah was buried, is identified by some traditions as a tree, marking personal and communal memory in the landscape.

Trees also served as sites of divine revelation: The burning bush that spoke to Moses became a miraculous medium for God’s command and covenant, teaching that nature itself can carry spiritual messages. In moments of survival, trees provided both sustenance and miracle; at Marah, God instructed Moses to throw the branch of an olive tree into bitter waters, sweetening them for the Israelites—a literal and symbolic demonstration of life-giving power.

Oases and groves also reflect the Torah’s intertwining of nature, spirituality, and community. At Elim, there were 70 palms and 12 springs, one for each tribe and elder, symbolizing unity, leadership, and divine provision.

Finally, the story of Jacob’s cedars emphasizes foresight, planning, and continuity: the cedars he planted were later used to construct the Tabernacle, illustrating the deep connection between cultivation, sacred architecture, and long-term spiritual preparation. Across these stories, trees are not mere scenery; they are witnesses, participants, and symbols of moral, spiritual, and communal life in the Jewish tradition.

Israel has hundreds of millions of trees for a population of approximately 10 million, resulting in an estimated 20–to–22 trees per capita. Due to extensive, decades-long afforestation efforts, the country has increased its forest cover from around 2 percent in 1948 to over 8 percent today.

Israel is unique for having more trees today than it did 100 years ago, focusing on planting in arid and semi-arid regions. While many countries have higher total tree counts, Israel’s per capita number is notable for an arid nation with a rapidly growing population, reflecting intensive reforestation initiatives.

In Israel, trees are considered not only ecological assets but also cultural and historical symbols. Many are protected under national law, particularly in urban areas and during development projects. The Planning and Building Law (1965) and related municipal regulations require developers to obtain permits before cutting or removing trees. This is designed to ensure that construction does not destroy valuable greenery or disturb ecological balance.

Certain trees are given special protection due to age, rarity, or historical significance. For example, centuries-old olive trees or ancient cypresses often cannot be removed under any circumstance. Even when a construction project is approved, these trees must be preserved, relocated, or otherwise accommodated.

In urban planning, Israeli law mandates green space preservation, requiring municipalities to integrate trees and parks into new neighborhoods. When trees must be removed for roads, buildings, or infrastructure, developers are generally obligated to replace them with equivalent or greater planting, often using native or climate-adapted species.

By the late 1800s, as the Ottoman Empire’s control over the Land of Israel waned, much of the land had fallen into neglect. The once-dense forests of the Galilee and the Carmel mountains had been heavily logged, while swamps spread and arid regions expanded, leaving the landscape scarred and vulnerable.

When Zionist pioneers arrived in Ottoman and later British Mandatory Palestine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, much of the land was marshy, malarial, and considered uninhabitable, particularly in the Hula Valley and along the coastal plains. Swamps were not only a health hazard but also an obstacle to settlement and agriculture. Early Zionist settlers had to find innovative ways to reclaim the land, and trees played a surprisingly practical role.

One of the most famous examples involves the importation of eucalyptus trees from Australia. The Australian blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus) was chosen because of its rapid growth and remarkable ability to absorb water. Planting these trees helped drain swamps and lower the water table, reducing mosquito-borne malaria and making previously inhospitable areas suitable for farming and settlement.

Beyond their practical purpose, these trees were also symbolically important. Planting forests was part of the Zionist project to “green” the land, reclaim it, and create a visible, living connection between the Jewish People and the Land of Israel. Organizations like the Jewish National Fund have sponsored tree-planting campaigns — resulting in over 250 million trees planted throughout Israel — and eucalyptus forests became a tangible sign of human ingenuity and national revival.

During and after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, many Palestinian Arab villages were depopulated or abandoned. Some residents fled out of fear during the conflict, while others were expelled amid the chaos of war. Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir famously said: “We do not rejoice in victories. We rejoice when a new kind of cotton is grown and when strawberries bloom in Israel.”

In the years that followed, the Israeli government and Zionist organizations often planted trees on the lands of these abandoned villages. There were several practical and environmental reasons for this. Many of the areas had been left bare and were at risk of erosion or overgrowth, so planting forests helped stabilize the land, prevent desertification, and develop national forests. Eucalyptus, pine, and other species were commonly planted to reclaim the land and make it productive or suitable for recreational use.

Today, planting trees in Israel has evolved into a sophisticated, tech-driven endeavor. Forestry teams carefully match each species to the specific climate and soil conditions of its region. In the north, saplings like Tabor oak, cypress, and eucalyptus are being nurtured for optimal growth. Central Israel focuses on broadleaf trees, chosen for their ability to create extensive green coverage while minimizing the risk of forest fires. In the south, researchers cultivate acacia, palm, fig, carob, and tamarisk seedlings, blending ecological strategy with the country’s long-term vision of greening arid landscapes.

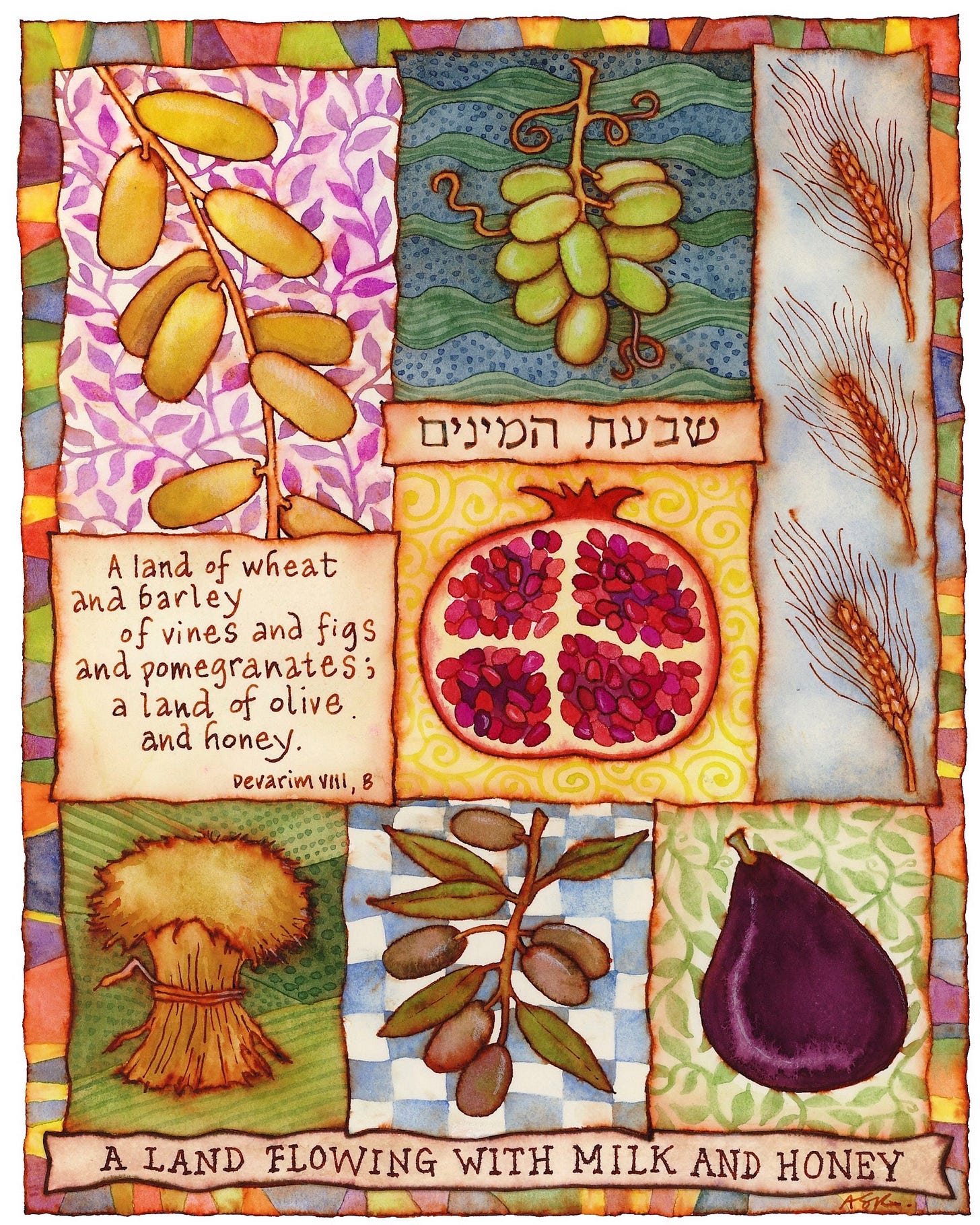

The Land of Israel is described in Scripture as uniquely blessed, “a land with brooks of water … a land of wheat and barley, [grape] vines and figs and pomegranates, a land of oil-producing olives and honey [from dates].”

These seven species are not just agricultural staples; they are intimately connected to the spiritual character of the land. They were so revered that there was a mitzvah to bring the first of these fruits, called bikkurim, to the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Each of these species provides nourishment, but more importantly, they symbolize the diverse spiritual energies that flow through the Land of Israel and into the lives of its people.

Mystical tradition associates each of the seven species with one of the seven sefirot, the Divine attributes that guide human character and spiritual service. Wheat corresponds to Chesed (kindness), barley to Gevurah (discipline), grapes to Tiferet (harmony), figs to Netzach (perseverance), pomegranates to Hod (humility), olives to Yesod (foundation), and dates to Malchut (royalty). Every soul contains all seven attributes, though each person has a dominant trait shaping their path. By eating and blessing these fruits, Jews symbolically engage with the full spectrum of Divine attributes, expressing spiritual completeness through the natural bounty of the land.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe emphasized that the seven species combine necessity and pleasure, reflecting the dual purpose of creation. Grain (wheat and barley) provides essential sustenance, while the five tree-grown fruits add beauty and delight to life. Spiritually, this teaches that serving God is not merely a matter of obligation or survival; it must also involve joy, desire, and wholehearted engagement.

On Tu Bishvat, which Jews refer to as the “New Year for Trees,” this lesson is celebrated by eating the fruits, especially those that grow on trees, and dedicating oneself to serving God with all seven Divine attributes from the very start of one’s spiritual journey.

Beyond personal growth, the seven species also channel Divine blessings to the world. Just as the Land of Israel is blessed, so too these fruits transmit spiritual energy and vitality, nurturing both body and soul. Each bite is a reminder that the natural world and human life are inseparable from Divine providence, and that pleasure, nourishment, and ethical growth can coexist.

In this way, the seven species are both practical and profoundly symbolic, connecting the physical, spiritual, and ethical dimensions of Jewish life.

Tu BiShvat is traditionally considered a “minor” holiday in Judaism. Unlike Rosh Hashanah, Passover, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot, it is not biblically mandated with ritual observances such as sacrifices or fasting. Its origins are primarily agricultural and legal: It was the date used in the Talmud to calculate tithes for fruit trees. For centuries, it was observed quietly, often with simple blessings over the first fruits of the season or reflection on the agricultural cycle.

However, the reestablishment of the Jewish state in Israel transformed Tu BiShvat into something much more significant. Planting trees became a national priority, both as an ecological project and a symbolic act of nation-building. The holiday evolved into a celebration of the land itself, emphasizing Zionist ideals of renewal, growth, and continuity. What was once a minor agricultural date now inspires mass tree-planting campaigns, school programs, and national ceremonies. In this way, the modern Jewish state has elevated even small, modest holidays, connecting them to identity, territory, and collective purpose.

Other holidays have experienced similar transformations. Lag BaOmer, for example, was historically a minor date marking the 33rd day of the Omer count and the cessation of a plague among Rabbi Akiva’s students. Today, it is widely celebrated with bonfires, pilgrimages to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai’s tomb in Meron, parades, and communal festivities. Purim, too, though biblically commanded, was historically a relatively low-key festival; in modern times, it has become a widely celebrated holiday with costumes, plays, and communal festivities that rival the major festivals in public prominence.

In short, the modern recreation of the Jewish state has had the effect of amplifying minor holidays, giving them national, cultural, and even political weight. Even holidays that once existed primarily as legal or agricultural markers are now opportunities to celebrate Jewish identity, connection to the land, and the continuity of our people.

When it came to decide on how to celebrate our daughters’ Bat Mitzvah, they chose a trip to Israel instead of the usual, “over the top” parties. We planted trees in the names of their friends and gave each a certificate upon our return.

Fascinating and beautiful — I learned a lot from reading this. And I must say, the one time I went to Israel, as an Aussie (non-Jewish), that was almost the first thing I noticed: gum trees (as we call eucalyptus). So many gum trees. Everywhere. That was one thing that made me feel right at home — although the more important things that did that were the kindness of all the people we met, and the beauty of the land and the thousands of years' worth of history and holiness. But the gum trees definitely also made it special to me. 🥰