The Day of Atonement is also the Day of Contradictions.

We are told to forgive, but what if forgiveness makes things worse?

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Yom Kippur is called the Day of Atonement, but it might just as well be called the Day of Contradictions.

At its heart, the day is about forgiveness — God’s forgiveness, our forgiveness of others, and perhaps most difficult of all, forgiveness of ourselves.

Yet the path to forgiveness is full of tensions, paradoxes, and seeming opposites that we are asked to hold at the same time.

We are told not to have too many expectations of people. After all, disappointment is the root of resentment. And yet, healthy relationships are built on give and take, on the expectation that those we love will show up for us, just as we show up for them.

We are told that people don’t change, that past behavior is the best predictor of future behavior. And yet, life is meant to be a constant evolution, where growth and transformation are not just possible, but necessary.

We are told to forgive others for our own sake, because holding onto bitterness poisons the one who clings to it. And yet, forgiveness often feels incomplete if it comes without apology, responsibility, or change from the one who caused the harm.

We are told that time heals all wounds. And yet, some wounds grow sharper with time, their sting deepening if never acknowledged.

We are told that we must let go. And yet, sometimes the act of remembering — holding onto a lesson, a boundary, a scar — is itself a form of healing.

We are told to love people as they are. And yet, we should also love people for who they are becoming, thus encouraging their growth.

We are told to forgive seventy times seven. And yet, there are times when to forgive too quickly is to enable, to allow harm to continue unchecked.

We are told that God’s forgiveness wipes the slate clean. And yet, the whole point of teshuvah — return — is that the slate is not erased but rewritten, that the story of our lives must include the wrong turns we took, the confessions we made, the repairs we attempted.

We are told to take accountability. And yet, how does one deal with people who never take accountability?

We are told to forgive. And yet, what if forgiveness hurts the victim because the perpetrator is never held accountable — by others or by themselves?

We are told that silence is golden. And yet, when someone has hurt us, why does silence feel like betrayal, both to ourselves and to truth?

We are told to be strong. And yet, strength sometimes means admitting weakness, asking for help, or confessing failure.

We are told to turn the other cheek. And yet, Torah also teaches that justice demands accountability and that wrongdoing cannot be ignored.

We are told it’s not what you say, but how you say it. And yet, some people never hear the message when you dance around it.

We are told to forgive and forget. And yet, forgetting can erase lessons hard-won through pain, while memory can protect us from repeated harm.

We are told to give people second chances. And yet, sometimes second chances become second wounds.

We are told to mind our own business. And yet, turning away from injustice only deepens the harm.

We are told that God is infinite in mercy. And yet, tradition also says even God cannot forgive the harm we do to one another until we make it right.

We are told to love ourselves. And yet, self-love without self-critique can become arrogance.

We are told blood is thicker than water. And yet, chosen family often carries us more faithfully than the families we were born into.

We are told patience is a virtue. And yet, waiting too long can mean losing the moment for change.

We are told that prayer changes things. And yet, sometimes the only thing prayer changes is us.

We are told not to be too hard on ourselves. And yet, sometimes the only way we grow is by facing ourselves honestly.

We are told to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes. And yet, some people never take their shoes off long enough to let anyone in.

We are told success is the goal. And yet, success without integrity leaves us empty.

We are told to put the past behind us. And yet, the past has a way of following us until we face it.

We are told that time changes everything. And yet, some people remain frozen, repeating the same patterns year after year.

We are told to move on. And yet, moving on too quickly can mean we never truly move through.

We are told that love covers over all faults. And yet, love also demands truth-telling, boundaries, and honesty.

We are told to be patient. And yet, patience with injustice can look a lot like complicity.

We are told to give people the benefit of the doubt. And yet, sometimes doubt itself is what keeps us safe.

We are told that God is merciful. And yet, we also call God just — and justice and mercy do not always align easily.

We are told that family is everything. And yet, some families wound more than they heal, and sometimes the holiest act is knowing when to step back.

We are told that you cannot parent your children once they are grown. And yet, some grown children remain children still, carrying the struggles of adulthood without the maturity to bear them.

We are told that fasting elevates us. And yet, our hunger reminds us just how human we are.

We are told to “repair the world.” And yet, how can we repair the world if we have not first learned how to repair ourselves?

We are told to keep the peace. And yet, peace without justice is no peace at all.

We are told to love our neighbor as ourselves. And yet, what if our neighbor does not live by the same covenant of care?

We are told to follow our heart. And yet, the heart without wisdom can lead us astray.

We are told to stand up for all injustices. And yet, what happens when the injustice is in our own backyard, when the harm is done directly to us?

We are told to condemn corrupted politicians from the other side. And yet, what do we do when leaders from our own side commit the very same wrongs?

We are told that change takes time. And yet, a single moment of courage — one apology, one decision, one act of return — can transform a life indefinitely.

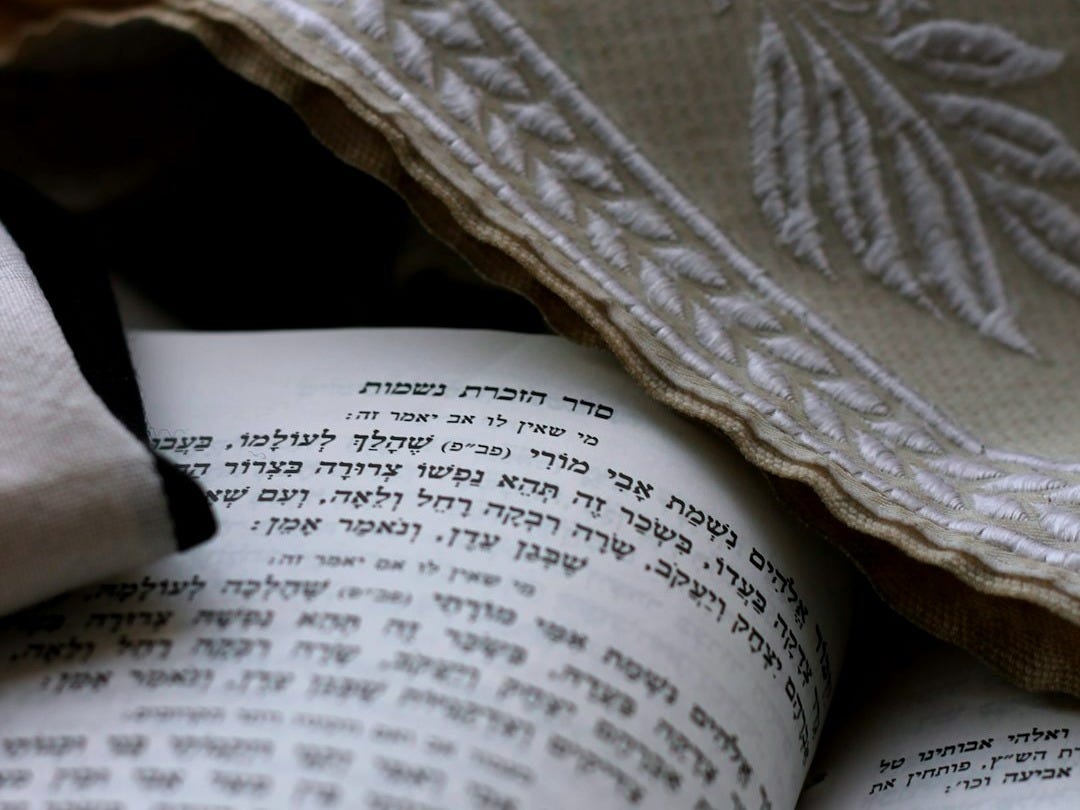

Jewish tradition wrestles openly with these contradictions. The Mishnah teaches: “For transgressions between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones. But for transgressions between one person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until they have appeased their fellow.”1

Forgiveness, in other words, cannot bypass accountability. Without seeking reconciliation, even God cannot erase the harm. Maimonides deepens this, explaining that teshuvah requires four steps — regret, confession, resolve, and change. Anything less is incomplete.

But it is not only others we struggle to forgive. We are told to forgive ourselves, to move forward. And yet, forgiving ourselves often feels hardest of all; we replay mistakes endlessly, holding ourselves to standards we would never impose on a friend.

We are told that guilt is destructive. And yet, without guilt, there can be no growth. The challenge is learning the difference between paralyzing guilt that imprisons us, and productive remorse that propels us.

And then there is the future. We are told that forgiveness is about closure. And yet, perhaps forgiveness is more about possibility — keeping open the door that says tomorrow can be better than today.

We are told that the past defines us. And yet, Yom Kippur insists that the future is still ours to shape.

Yom Kippur does not resolve these contradictions. Instead, it asks us to sit inside them. To fast not only from food and drink, but from easy answers. To acknowledge that forgiveness is not a single act but a tension, a dance between mercy and accountability, letting go and holding on, accepting what is and yearning for what could be.

Forgiveness is never just one thing; it is both release and responsibility. Both expectation and acceptance. Both memory and renewal. On Yom Kippur, we are reminded that living with these two sides is not a weakness; it is the very essence of being human.

Yoma 8:9

Wow! On a day when I will be absorbed in the beauty of the machzor, this is likely the most thought-provoking reading I will do all day, May I never subject my offspring to another platitude.

A wonderfully expressed set of tensions, Joshua. It's true that the Day of Atonement is a Day of Contradiction but I don't think it's *the* day of contradiction since to anyone reasonably observant, not of Judaism per se, but of the world around them and what is inside their own thoughts and feelings, it should be transparent that most if not all days are days of contradiction. Therefore, Yom Kippur would not be special if it were merely what one encounters daily. It would be an unmarked day. Anyway, here is another seeming contradiction: it's customary to wish others an easy fast, but if the act of fasting is to take us out of our local minima of daily life, shouldn't the fast be challenging? To wish that it be easy seems to me to defeat the purpose of temporarily escaping from daily comfort seeking. To that end, I wish all of you fasting today a meaningful fast and a successful escape from your local minima of everyday life. May you resettle on a more favorable point, on a better local minimum for the new year.