When 'The Holocaust Is Fake' Shows Up on Your Street Corner

Between silence and response lies the fragile space where memory lives — and where history asks to be seen again.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay by Aviya Kushner, the author of “Wolf Lamb Bomb” and “The Grammar of God.”

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

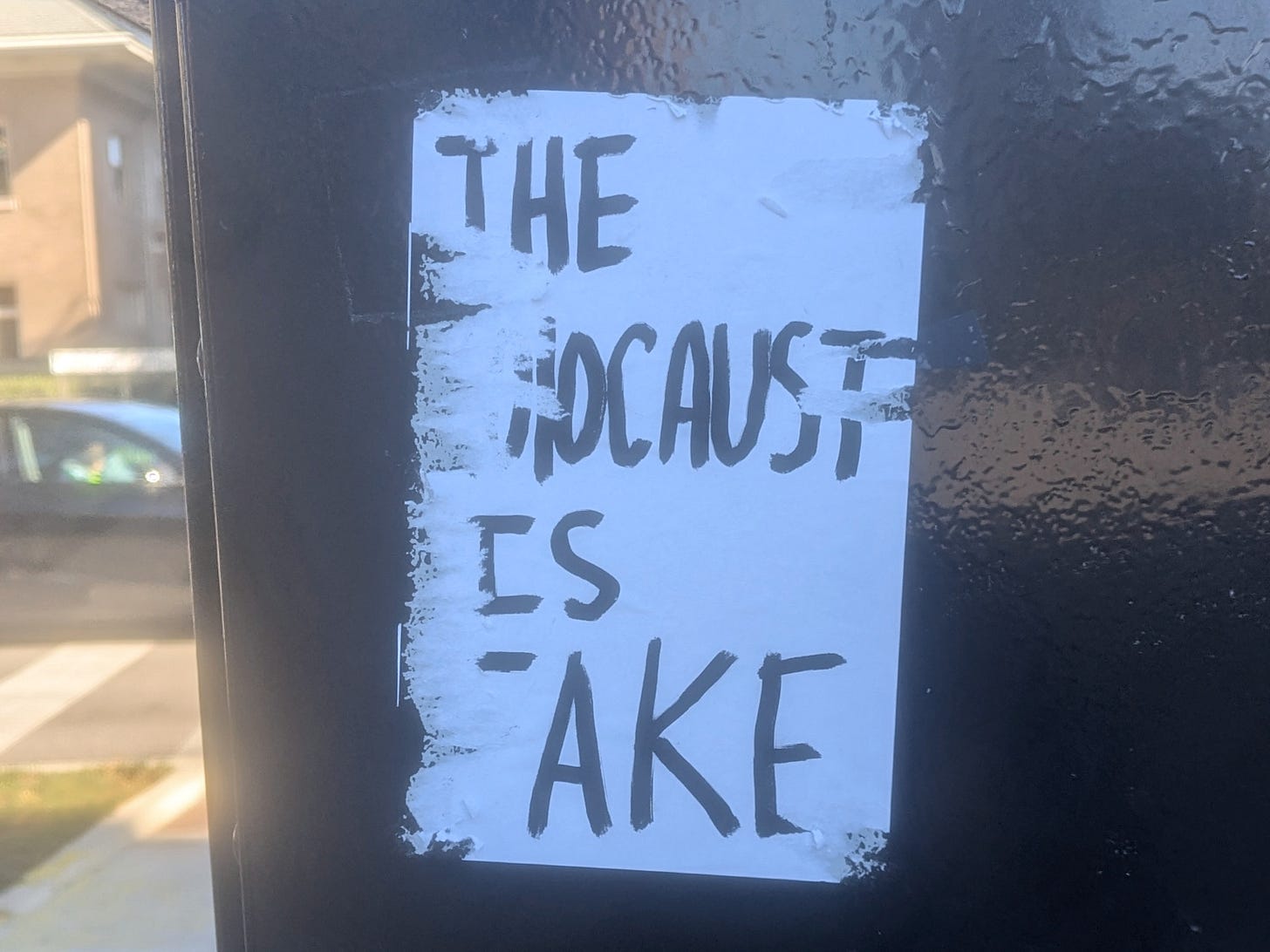

Recently I had the unpleasant experience of discovering a sticker asserting that “The Holocaust is fake,” in capital letters, on my street corner in Chicago.

At first, I thought: I don’t want to write about this. But I did want to document it, so I went home, brought an older Jewish neighbor with me, and together we took some photos.

Then I had second thoughts. If I don’t want to write about this, who will?

I drafted an email to an editor with the subject line “I want to respond to this.” And I remembered returning to the city in Germany where my grandfather grew up, for the second time. I remembered how much I did not want to go back. But then, I realized that I had to.

I had to look, and more accurately, I had to look again and again. In other words, I had to respond.

I find that I still have to fight the desire not to respond, to just live my life. And I think many of us are struggling between the need to respond and the desire not to respond, in this fraught moment which seems to get harder and harder.

I have since returned to Bremen again and again, and I am grateful that I have been able to do that, because each visit deepened my understanding. I saw layers of history and contemporary reality that I am still thinking through.

But gratitude wasn’t what I was feeling when I saw that “The Holocaust Is Fake” sticker on my street corner and all over the far north side of Chicago, traditionally a Jewish neighborhood. Gratitude wasn’t what I was feeling as I found myself not posting the essay I wrote in response on social media.

“I feel that my circles are getting smaller and smaller,” a much-loved friend said to me recently, as we discussed recent events. “Yes,” I thought, “and that’s dangerous.”

But this week, someone covered up the sticker and left a commentary of sorts. I thought you might be interested in seeing the two sets of stickers. And then yesterday, on the anniversary of Kristallnacht, I realized that I have to share it.

In my first book, “The Grammar of God,” I talked about how the desire not to respond was overwhelmed by the need to respond. One chapter features a story about the narrator and her mother taking a quiet train north from Hamburg to Bremen, retracing the steps of their family’s past.

As the city fades behind them, she reflects on her grandfather’s childhood there: a Hasidic boy who loved art and color in a world that didn’t allow it. The trip is both a pilgrimage and a reckoning. Her great-grandmother Rachel, the family matriarch, was killed in the Holocaust, and this journey is the granddaughter’s way of “starting” — of confronting what remains and what was erased.

In Bremen, the mother and daughter stand in the same train station where the grandfather last saw his parents and four brothers before escaping to British Mandate Palestine. With directions written in his hand, they set out to find the family’s old home. Guided by a young Israeli they meet by chance, they reach Vahrerstrasse and discover the house — above a beer bar, just as her grandfather described. The landlord, a man about her grandfather’s age, turns pale at their presence and angrily orders them to leave.

Yet the narrator feels certain he remembers. She photographs everything — the house, the street, the man — determined to preserve proof that someone from the Traum family came back.

When they return to Israel, the grandfather refuses to look at the photos. The memories are unbearable. He rages against the past, reliving the terror of Germany in the 1930s. But the rest of their time together reveals another side of him — the man who loved art, fine wine, and beauty. Surrounded by books, sculpture, and music, he embodies the reconciliation of faith and aesthetics that began with his mother’s small act of permission. To him, beauty — ha’dvarim hayafim in Hebrew — is sacred, an affirmation of life after devastation.

The story closes in the Galilee, where the family gathers as the narrator’s brother chants Isaiah’s words of comfort. The haunting echo of prophecy (“Comfort, oh comfort my people”) binds generations together. Out of loss, art, and remembrance, the family continues the work of atah hachilota — you have begun. The journey to Bremen becomes not just a return to trauma, but a reaffirmation of survival, beauty, and faith.

Now, let’s return to the present. There is so much happening right now, in contemporary history — in America, across the West. In Israel, the released hostages are slowly sharing harrowing details of what they experienced. Last week, former Israeli hostage Rom Braslavski said he was sexually abused in captivity by Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

“They stripped me of all my clothes, my underwear, everything. They tied me up while I was completely naked. I was torn apart, dying, with no food,” recalled Rom. “It was sexual violence, and its main purpose was to humiliate me. The goal was to crush my dignity. And that’s exactly what he did. … It’s something even the Nazis didn’t do. During Hitler’s time, they wouldn’t have done things like this.”

And I have been thinking about the word “response” in English, and how perhaps the Hebrew word teshuva is a better choice for this moment. Teshuva means an answer, a response, but of course it also means repentance.

It so happens that the wonderful Hebrew poet Lea Goldberg has a poem titled “Teshuva,” translated as “Answer” by Rachel Tsivia Back.1 As you can see, the first two lines are an epigraph, and explain the inspiration for the poem.

To the exam question “For what purpose

are lyric poems written in our era?”

And what would we do with the horses in the twentieth century?

And with the does?

And with the large stones

in the Jerusalem hills?

But that question — “for what purpose…” — haunts me almost as much as the translation issues behind translating teshuva as answer. Sure, that is what it means, but how about everything else teshuvah means?

Lea Goldberg is a household name in Israel, though she is far less known in the English-speaking world. In addition to her poetry, she was also a marvelous author and translator of children’s literature, and many children can recite her works by heart. She knew seven languages, and was a prolific translator into Hebrew.

Goldberg’s life is a microcosm of 20th-century Jewish history. She was born in East Prussia (now Russia) in 1911, and raised in Lithuania. She began writing poetry at 12 years old, “profoundly shaped by her family’s exile from Russia to Lithuania and her father’s imprisonment and subsequent breakdown.”2

Goldberg studied literature and philosophy at universities in Kovno, Berlin, and Bonn before leaving Europe behind in 1935 for British Mandate Palestine. That same year, she released her debut poetry collection, “Smoke Rings,” introducing readers to her distinctive voice — elegant, restrained, yet full of longing.

In the 1940s, her poetry lingered in the landscapes of her childhood, tracing the memory of Eastern Europe through language and loss. By the 1950s, her work turned inward, probing the quiet spaces of love, imagination, and solitude — most notably in her 1955 collection “Morning Lightning.”

Around that time, Goldberg joined the faculty of Hebrew University, where she taught Russian literature and nurtured a generation of writers who, like her, straddled the old world and the new.

I was intrigued by that emphasis on silence — or, perhaps, non-response.

Goldberg was also a journalist, at the Israeli newspapers Ha’aretz and Davar and was a children books’ editor at Sifriyat Po’alim (“The Workers’ Library”) publishing house. She was active in theater, too, as a literary consultant to the Habima Theatre (Israel’s national theatre) and as a theater critic for Al Ha-Mishmar journal.

In 1970, Goldberg was awarded the Israel Prize posthumously.

But all of this biographical information doesn’t capture how Goldberg captivated a younger generation of Israeli writers, and how beloved she is among so many Hebrew readers. Sometimes I find that reading a substantive review essay is a good entry point to a poet, and I can recommend one for those who aren’t familiar with Goldberg.

For the Jewish Review of Books, translator and critic Shoshana Olidort reviewed Rachel Tsivia Back’s translation of Goldberg’s poems, including “Answer.” I was struck by this passage in Olidort’s review essay:

“Silence and loneliness are leitmotifs in this collection. An early poem titled ‘There Are Many Like Me’ Goldberg began, ‘There are many like me: lonely and sad, / one writes poems, another sells her body, / a third convalesces in Davos, / and all of us drink thirstily from the bitter cup.’ The poem ends: ‘There is no escape.’ These sentiments are sharpened in the later poems, and though their expression is more sophisticated, they remain fundamentally unchanged.”

Is there an escape?

Sometimes I think there is an escape in answering, in responding. Sometimes I think there is an escape in return, as illogical as that sounds. Sometimes I think there is an answer in teshuva, in repentance.

Lea Goldberg’s three questions — in one short poem of answer — have the tinge of all of that, along with our strange human desire to find answers in questions.

“On the Surface of Silence: The Last Poems of Lea Goldberg.” University of Pittsburgh Press.

The Jewish Woman’s Archive

I was in the US Army in Germany in the 1960's in Oberpfalz/Bavaria where I was a spy for the Army division of NSA. I learned passable German in addition to my Warsaw Pact language.

I visited Dachau, not far from Munich. I also visited Flossenburg - 75 km away. Flossenburg was where Hitler had Dietrich Bonhoeffer executed days before the war ended.

Do you know how many concentration camps the Nazis had? 1,000 of them plus 30,000 slave labor camps and then the Vernichtungslager. These were the death camps: Sobibor, Auschwitz/Birkenau, Chelmno, Majdanek, Belzec and Treblinka. You lasted a day or so there - that's it - the end.

If you ever run in to someone who denies the Holocaust ask them what camps they have personally visited, because I can personally tell you that you won't forget it and you won't put up with with Holocaust denial either.

You might as well deny the Atlantic Ocean or the Moon.

Thank you for the beautiful introduction to the poetry and life of Leah Goldberg... I know many of the Hebrew children's books and songs but I am looking forward to reading her in English...