Jews appeased the 'woke' Left — and it backfired.

He spent his career fighting for justice. Then he realized he was fighting the wrong fight. Indeed, many Jews fell for the "woke" lie.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay by David Roytenberg, a former writer for the Canadian Jewish News.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Recently, we started reading a book we’ve had on our shelf for a while — “Woke Antisemitism” by David L. Bernstein.

The book describes the author’s career in Jewish human rights organizations and how he eventually realized that he had stopped believing in the work he was doing — work which made him complicit with “woke” ideology.

In response, he has turned his attention to the pressing challenge of fighting to defend liberal values and confronting the threat to Jews from a new orthodoxy, which he calls “woke antisemitism.”

David L. Bernstein begins his book by harking back to his own upbringing as a Jewish liberal in the 1970s and 1980s. Key values he took away from that upbringing were a belief in freedom of expression (which he calls liberalism in the classical sense) and a belief that society should help those who were doing less well (which he calls liberalism in the political sense).

He identifies freedom of expression, and the expectation that everyone should be able to argue for their ideas, as core Jewish values, reflected in the lively debates that went on around the family dinner table. He reminds us that this idea is embodied in Jewish tradition as Makhloket l’Shem Shamayim (an argument for the sake of heaven).

During his college years in the late 1980s at Ohio State University, he encounters manifestations of the opposite impulse: the silencing of unorthodox opinions in the name of justice. He enrolls in a women’s studies course with the aim of challenging some of the ideas he disagreed with, only to drop the course after realizing the professor would fail him if he wrote honestly about his own views of the course material — views which rejected the dogmas underpinning what she was teaching.

As a member of the campus Hillel leadership, he succeeds in barring a Jewish extremist, Meir Kahane, from using the Hillel facility (due to his racist views), only to discover that the university itself paid to bring in Stokely Carmichael, whose views he finds equally deplorable. Attending the Carmichael event, he hears the speaker say that the only good Zionist is a dead Zionist.

Bernstein begins his career working for the Jewish community of Greater Washington, D.C., in 1993, just after the Oslo Accords1 agreements were signed at the White House. It is a time of unprecedented goodwill between Jews and Arabs. The author believed that the biggest Jewish concern of the day was not antisemitism, but whether the Jewish community would continue to thrive in America or if, instead, Jews were doomed to assimilate into American culture and disappear as a distinct group.

As we know, the notion that antisemitism was on a permanent decline turned out to be a mistake. The period of goodwill was very short-lived and was succeeded by an era of unprecedented hostility to Zionism and to the majority of Jews who support it. Bernstein argues that the organized Jewish community failed to recognize the ideological roots of the resurgence of hostility to Israel and Zionism. As a result, the strategies they pursued were ineffective.

He explains that the new “anti-Zionism” was rooted in post-colonialism, an ideology that asserts that the social and economic disparities in the world are the fruits of colonialism, and that attempts to attribute these disparities to other causes are racist. It also implies that nations enjoying economic success are benefiting from the exploitation and oppression of the parts of the world that are less successful. According to the author, the ideology is built around a kernel of truth: Colonialism has caused lasting harm.

But, by identifying it as the single explanation for disparities between nations, it leaves no room for identifying cultural factors that help societies succeed, and it ignores the more successful post-colonial societies in Asia and elsewhere. In hindsight, this is an ideology that was bound to be used to discredit the State of Israel.

From Anti-Racism to Antisemitism

Bernstein turns to an account of his work for the American Jewish Committee, where his focus was on strengthening relations between the Jewish and Black communities. He describes successful collaborations that helped Black participants enter and advance in the American commercial real estate business, which had few Black participants at the start. He also writes frankly about problems he observed involving incompetence and corruption among Black leaders, who presided over the failure of the Washington, D.C., public school system — problems acknowledged by at least one of the Black leaders he worked with.

During this era, he dealt with the gradual acceptance of Louis Farrakhan as an important leader of the Black community, in spite of Farrakhan’s vicious antisemitism. Jewish leaders who tried to get their Black interlocutors to shun him ultimately failed and encountered resentment that Jews wanted his antisemitic views to be treated as beyond the pale.

Bernstein recounts his first encounter with a new form of diversity training, which was initially called “multiculturalism,” and which focused on getting white individuals involved in the training to acknowledge their own racism. The core idea that everyone was supposed to believe was that all social disparities are caused by racism. White people who can’t see this are blinded by their own privilege.

Bernstein’s objection to this approach is similar to our own. While racism certainly accounts for some of the problems faced by disadvantaged members of society, the insistence that it is the only explanation seemed to him — and seems to us — to be both false and counterproductive, in that it shuts down any effort to uncover and fix other causes of social inequality, in particular causes that are rooted in the disadvantaged community.

By 2003, Bernstein had realized that there was a common thread connecting the multiculturalism gaining popularity in America and the post-colonialism that increasingly treated Israel’s successful economic and social development as the fruits of colonialism. In both cases, models of success that had once been admired and seen as examples to emulate were being recast as unearned benefits won by trampling on the rights of others.

In the same way that post-colonialism turned all the achievements of Zionism into crimes against the people of “Palestine,” the new model of multiculturalism — and its successor ideology of anti-racism — turned Jewish success into the unearned fruits of white privilege. Just as a post-colonialist approach to international affairs was an ideology designed to discredit the State of Israel, the new “anti-racism” social ideology, now referred to as Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), led inevitably to resentment and suspicion toward the success of the American Jewish community.

Ending Complicity

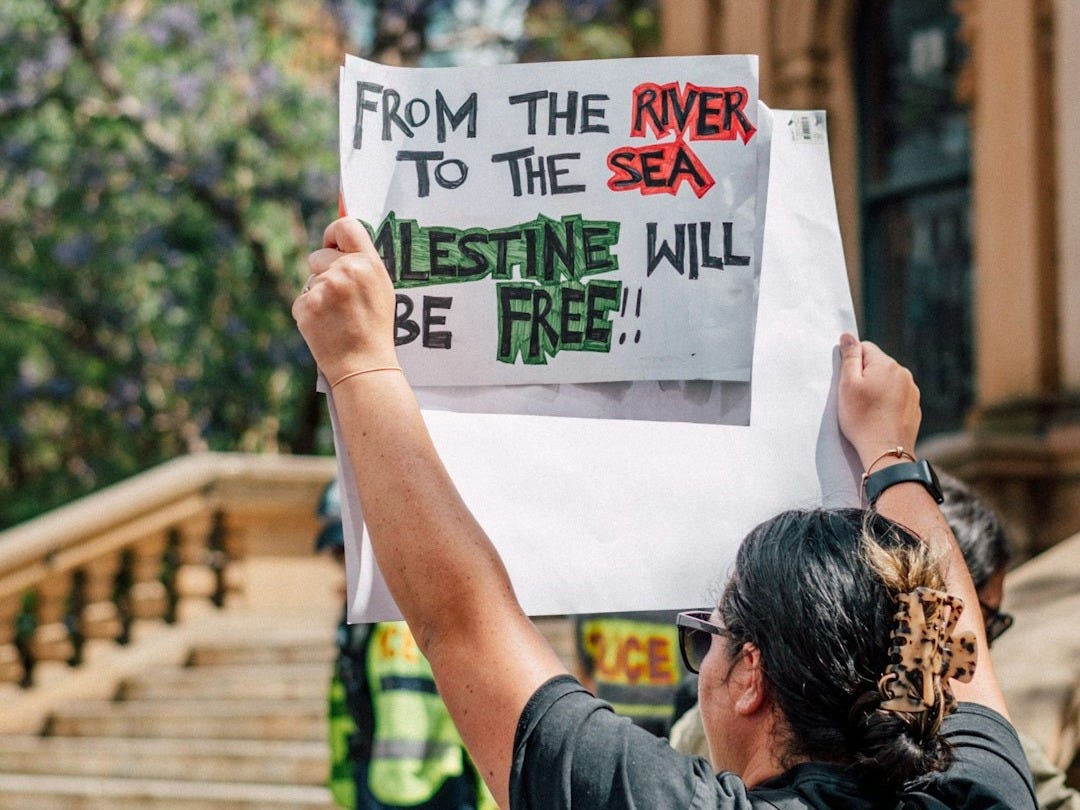

In the next few chapters, Bernstein explains how the historic alliance of the Black and Jewish communities led many progressive Jewish organizations to ally themselves with the Black Lives Matter movement. This happened despite the fact that the ideology pushed by the movement was rooted in the flawed ideas of post-colonialism, and the emerging belief that all social disparity in America was caused by racism. Jewish progressives tried to maintain ties even though the spokespeople for the Black Lives Matter movement put “anti-Zionism” at the heart of their message. Former Jewish allies such as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) were now denounced, accused of complicity in Zionism.

How did Jewish organizations find themselves aiding and abetting those working against Jewish interests? Bernstein recounts a story from 2012 about his work at “The David Project,” which was dedicated to countering campaigns on campus promoting Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) against Israel. The David Project brought a young Black student leader and BDS supporter on a trip to Israel. As a result of the trip, she changed her mind about BDS and apologized for her previous stance.

Inspired by this success, he brought in a trainer to campus to talk about the best way to oppose BDS while engaging with members of various minority groups. One woman attending the training objected that before trying to persuade members of minority groups to support Jewish interests, the participants should first “acknowledge their privilege.” She challenged the right of people who were not members of particular groups to advocate that they take a particular position. This was Bernstein’s first experience of a now-common phenomenon in which staff feel empowered to disrupt the work of organizations they are part of in the name of anti-racism.

By 2016, Bernstein had left The David Project and taken on the leadership of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs. He began to sound the alarm about the spread of the idea of intersectionality. This idea was originally developed to acknowledge that people belonging to more than one disadvantaged group might suffer overlapping causes of harm. Now it was being used to persuade social and political organizations working for many different causes that their cause was inseparable from the cause of the Palestinians.

In the process, the proponents of this idea falsely painted Israel as a European settler-colonial project. When Bernstein wrote an article articulating these ideas, he encountered angry resistance from progressive Jewish organizations that saw intersectionality as a cornerstone of the social justice movement they were part of. In response to this backlash, he looked for a way to link the Jewish narrative with the intersectional framework. He backpedaled on his condemnation of the concept.

This process of recanting one’s own positions in order to get a seat at the table in progressive spaces was the devil’s bargain that Bernstein and other Jewish leaders entered into, in hopes of keeping a channel open for the Jewish narrative. Unfortunately, it soon became clear to him that in the “woke” worldview, Jews were seen as part of the power structure, and as such their only appropriate role was to listen and learn, and to adopt the dogmas of “woke” ideology without question. Specifically, they were required to acknowledge their racism and cease making any demands on others to accommodate Jewish priorities.

Bernstein recounts a number of experiences that clarified the futility of giving in to “woke” ideology. He explains his gradual recognition that Jewish organizations dedicated to liberal values in general, and to a place for Jews in a liberal order in particular, had lost sight of their mission in a misguided attempt to maintain relationships with a highly illiberal new movement. This movement was not much interested in Jews, except insofar as they identified as members of other oppressed groups, or belonged to the minority who “acknowledged Jewish complicity” in systems of oppression, in both America and “Palestine.”

Policing Language

On the way to his decision to set a new course, Bernstein experiences how the vocabulary of “woke” ideology puts important topics of discussion “out of bounds.” One example that impacted their work was that by 2020, the term “Black-Jewish relations” was suddenly forbidden. Those who used it were called racist and accused of erasing Jews of color. Furthermore, any discussion of such matters was deemed inappropriate by anyone who was not a Jew of color themselves.

In another instructive experience, he attempts to conduct a meeting on certain topics related to race, such as how the group he led could engage productively in working for racial justice. Instead of addressing the issue, the discussion is deflected by a demand from one of the participants that, before having such a discussion, the people involved should do the work of acknowledging their own complicity in white supremacy. Bernstein finds that such interventions prevent any substantive discussion of the issue at hand. Attempts to find ways to make things better are derailed in favor of the recitation of “woke” dogmas about personal complicity in racism.

Bernstein sees firsthand how organizations with a social mission are being subverted from within, in the service of goals and beliefs that are not part of their mandate. He recounts incidents in which respected figures are brought down because something they say without malice is deemed offensive or harmful to people of color. Others who should have supported them remain silent in order not to be subjected to the same treatment. He acknowledges his own fault in failing to speak up for people who were being “canceled.”

Increasingly, he realizes that he is engaging in a kind of doublethink in order to say what is politically acceptable and keep himself out of trouble — and that often, he is saying things that he does not believe to be true.

He recounts that in July of 2020, Bari Weiss quit the New York Times following the dismissal of editor James Bennett. Bennett was fired for publishing an editorial by U.S. Senator Tom Cotton, which called for the deployment of troops to end rioting in American cities in the wake of the killing of George Floyd.

New York Times staff reportedly demanded his dismissal because the decision to publish the editorial made them feel unsafe. Weiss reported that some of these same staff harassed her for her political views and for being a Zionist. Shortly after leaving the Times, she published an article criticizing progressive Jewish organizations for supporting an illiberal movement hostile to Jewish interests and contrary to their own professed mission.

Backlash

Bernstein describes the angry response he got from Jewish progressives when he began to publicly criticize the Black Lives Matter movement for undermining liberal values and working against Jewish interests. In response, he published an article called “Six Questions Jewish Organizations Should Ask Themselves Before Taking a Stand on Racial and Critical Social Justice.” It amounts to a challenge to the core principles of “woke” ideology:

Do you believe America is a white supremacist society? How does that perspective comport with the previously common understanding of America as a pluralistic democracy that has sometimes failed to live up to its ideals?

Do you believe that non-marginalized communities should be able to opine about race and racism in a way that deviates from Critical Social Justice ideology or define racism (known as standpoint theory)? Does such a limitation on discourse affect the ability of people to engage in authentic dialogue or subject their own views and those of others to scrutiny?

Should Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) training impart to participants specific perspectives on how people should understand race and racism? Does such training run the risk of alienating people and exacerbating racial tensions? Have you looked at the research about the effectiveness of such training? Have you considered alternative approaches?

Does the new understanding of the concept of “equity” — that all disparities in outcome are ironclad proof of discrimination — make sense to you? What do you make of the fact that many non-white immigrant communities are, on average, doing better than white people? Do you believe that all disparities can be fully ameliorated in the here and now, as the new equity concept asserts, or over time by making investments in disadvantaged communities?

Do you value viewpoint and ideological diversity? If so, how do you intend to make space for lay leaders and professionals with different points of view moving forward?

Are there ways Jewish organizations can express commitment to a fair, free, and just society, consonant with Jewish values, that don’t require us to adopt wholesale Critical Social Justice ideology? Is there a third way?

In 2021, Bernstein helped prepare a public statement entitled “A Letter to Our Fellow Jews on Equality and Liberal Values.” Bernstein describes it as the defining manifesto of the new organization. It includes these words:

“Jewish tradition cherishes debate, respects disagreement, and values questions as well as answers. We members of the Jewish community add our voices to the growing chorus supporting our liberal principles, opposing the imposition of ideology, encouraging open discussions of challenging topics, and committing to achieving a more just America.”

After posting the letter on a Jewish educator’s Facebook group with 12,000 members, he was immediately reported by offended members, alleging that it was racist, and his post was taken down. A few days later, he was expelled from the group. This seemed to validate the concerns raised in the letter that debate on important social issues was being stifled.

In conversations with the head of a Jewish foundation, the author was told that they had come to believe that systemic racism was a very powerful force in American life. When asked if it was okay for people to disagree about race, the CEO replied that it was important to defer to Jews of color in that discussion. It wasn’t just that the ideology had been embraced by some Jewish organizations. It seemed that they no longer felt that they had the right to express their own views on the subject of race.

Bernstein points out that when someone abdicates their own power to make judgments and defers to a member of a particular minority group, this raises the problem of which member or members of that group to defer to. Inconveniently, members of racial minorities disagree about issues of race just as much as members of other groups.

A related idea is that young Jews tend to be more progressive, and that in order to reach them, organizations need to change their approach to be more in tune with their views. In this case as well, the question of who is right — or the fact that young Jews in fact have a complete range of opinions — is swept under the rug, and the people taking this approach abdicate their own responsibility to judge which ideas are correct.

Schools

The introduction of “woke” ideology in K–12 schools has been a particular concern for Jewish parents. However, it seems that Jewish organizations with a mission to protect Jews don’t necessarily recognize those concerns.

Bernstein describes how the ADL’s committee on extremism wrote a newsletter that characterized challenging “woke” ideology in schools as an attack on school boards. The ADL published an article on Critical Race Theory that characterized it as explaining why racial injustice persists in the U.S. Bernstein remarks that the ADL seems to treat Critical Race Theory as dogma rather than theory.

While the leader of the ADL has talked about the danger of Left antisemitism, Bernstein says the organization has not yet grasped the risks to Jews of promoting the idea that those who are successful in society are necessarily benefiting from unearned privilege. On a hopeful note, he writes that just before the publication of “Woke Antisemitism,” the ADL undertook a review of its education materials to identify those that are not aligned with its values.

Bernstein reports that the Reform movement in the U.S. and some Jewish day schools have also embraced training based on the new racial ideology. He sounds the alarm on the sort of Torah or pedagogy that is likely to emerge from such decisions.

‘Woke’ Ideology and Antisemitism

With its focus on structural racism and its call to whites to acknowledge their racism, “woke” ideology creates a fertile ground for antisemitism. Although the idea of linking identity to privilege is not antisemitic in itself, its positioning of Jews as white and privileged invites the expression of resentment toward Jews just as it invites expression of resentment toward American whites.

Bernstein analyzes in greater depth the way that the core ideas of “woke” ideology fuel antisemitism. He notes that Jews tend to thrive in liberal environments and to be viewed with suspicion in societies that promote ideological conformity.

Writing just after the outbreak of fighting in Gaza between Israel and Hamas in May of 2021, Bernstein notes that the news coverage of the conflict had grown much more hostile to Israel compared to earlier rounds. Coverage of previous rounds of fighting always began by explaining Hamas’ latest atrocity and acknowledging that Israel needed — and had the right — to do something about it. In 2021, this aspect of the coverage was less evident. Israel’s account of what it was doing in Gaza and why did not get the airtime or respect that it previously had.

Reading this from the perspective of 2025, this observation seems particularly prescient — and a bit quaint. It’s hard to remember a time when news coverage of fighting in Gaza included a fair account of Israel’s point of view.

In other settings, demands that Jews identify as white and own their racism, which were part of mandatory anti-racism training in some workplaces, were identified as “erasive antisemitism” and a “de facto undermining of the Jewish narrative of self-determination” by an Israeli think tank called the Reut Group.

Another worrisome concept that emerged as a result of “woke” ideology was “Jewish Privilege.” This was originally promoted by Right-wing antisemites trying to hitch a ride on the “woke” trend, but it has been picked up by other groups and even by progressive Jewish groups. This promotes the classical antisemitic idea that Jews benefit from some sort of unearned privilege, which accounts for their accomplishments and economic status.

Another idea that leaves Jews vulnerable is that any attempt to raise concern about antisemitism undermines anti-racist work. This has led to a reluctance to recognize and deal with explicit antisemitism when it arises. Jews who attempt to raise the issue are accused of decentering the “real work” against racism.

Warnings About a Future That Has Already Arrived

Bernstein concludes his book with an overview of the connections between “woke” ideology and antisemitism and a warning that existing trends could soon lead to conditions that are far worse for Jews. From the perspective of August 2025, these warnings are prescient.

One concern is that identity politics on the Left may fuel identity politics on the Right. The strong political reaction against DEI certainly seems to have been a factor in securing a second term in the White House for Donald Trump.

Bernstein also highlighted situations where Jews were being pushed out of progressive coalitions due to the adoption of explicitly “anti-Zionist” language by groups dedicated to other causes. He saw this as a risk that Jews would eventually be marginalized in much of American society. This is another phenomenon that has become much more widespread in the years since the publication of the book.

Still other risks identified included the “Corbynization”2 of American politics. While a few noisy “anti-Zionists” in the Democratic Party caucus did not represent the mainstream of the party, there was a risk, Bernstein wrote, that the Democrats would eventually embrace leaders who were hostile to Israel and Zionism. The recent victory of Zohran Mamdani in the Democratic Party primary for Mayor of New York City represents a step in that direction.

Bernstein highlighted a great increase in DEI professionals hired at American universities, reaching 45 per institution. He reports on a study that examined the social media behavior of these DEI professionals. The study found that they posted on Twitter three times as often about Israel as about China, and that only 4 percent of the Israel posts were positive, as opposed to 67 percent of the China posts. Bernstein suggested that there was some risk that Jews on American campuses might feel increasingly unwelcome.

Bernstein’s message is clear: The fight for liberalism — true liberalism — is not a spectator sport. If Jews, and indeed anyone who values freedom of thought and honest debate, want to preserve an open society, they must be willing to defend it. That means speaking uncomfortable truths, rejecting ideological conformity, and rebuilding the courage to disagree without fear.

The Oslo Accords are a pair of interim peace agreements signed in 1993 (Oslo I) and 1995 (Oslo II) between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Brokered in secret in Norway and signed at the White House, they established the Palestinian Authority to provide self-governance and recognized Israel’s existence, aiming to pave the way for a five-year transition to a permanent peace settlement based on UN resolutions.

“Corbynization” is a term referencing the political ideology and movement associated with Jeremy Corbyn, the former leader of the UK Labour Party. In the United States, “Corbynization” is used to warn against the political direction of the Democratic Party’s Far-Left factions.

Federations must remove all vestiges of DEI from their organizations and from the organizations that receive funding - especially day schools. DEI and “progressive” ideologies harm us and our children.

As a High School teacher in Brooklyn, NY I experienced this first hand. I was definitely taken aback and could not believe how DEI etc. had taken hold. I was vocal in my disagreements. It certainly earned me the least popular colleague award. However, I believe I made an impact on a few and also my students. It was also good to do as others who held my values did not feel alone.I taught my students to question everything and research for themselves. We can all, in our own worlds, fight, fight, fight. We must. They cannot win. It would be a very sick, toxic, and especially dangerous, environment for Jews. We cannot allow that. Thank you for this article. It is very important for Jews to hear this. I encourage everyone to share widely.