Denazifying Gaza

Germany’s denazification after World War Two is often cited as the model example. But what exactly did it involve, how was it implemented, and did it succeed?

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay by Nachum Kaplan, who writes the newsletter, “Moral Clarity.”

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

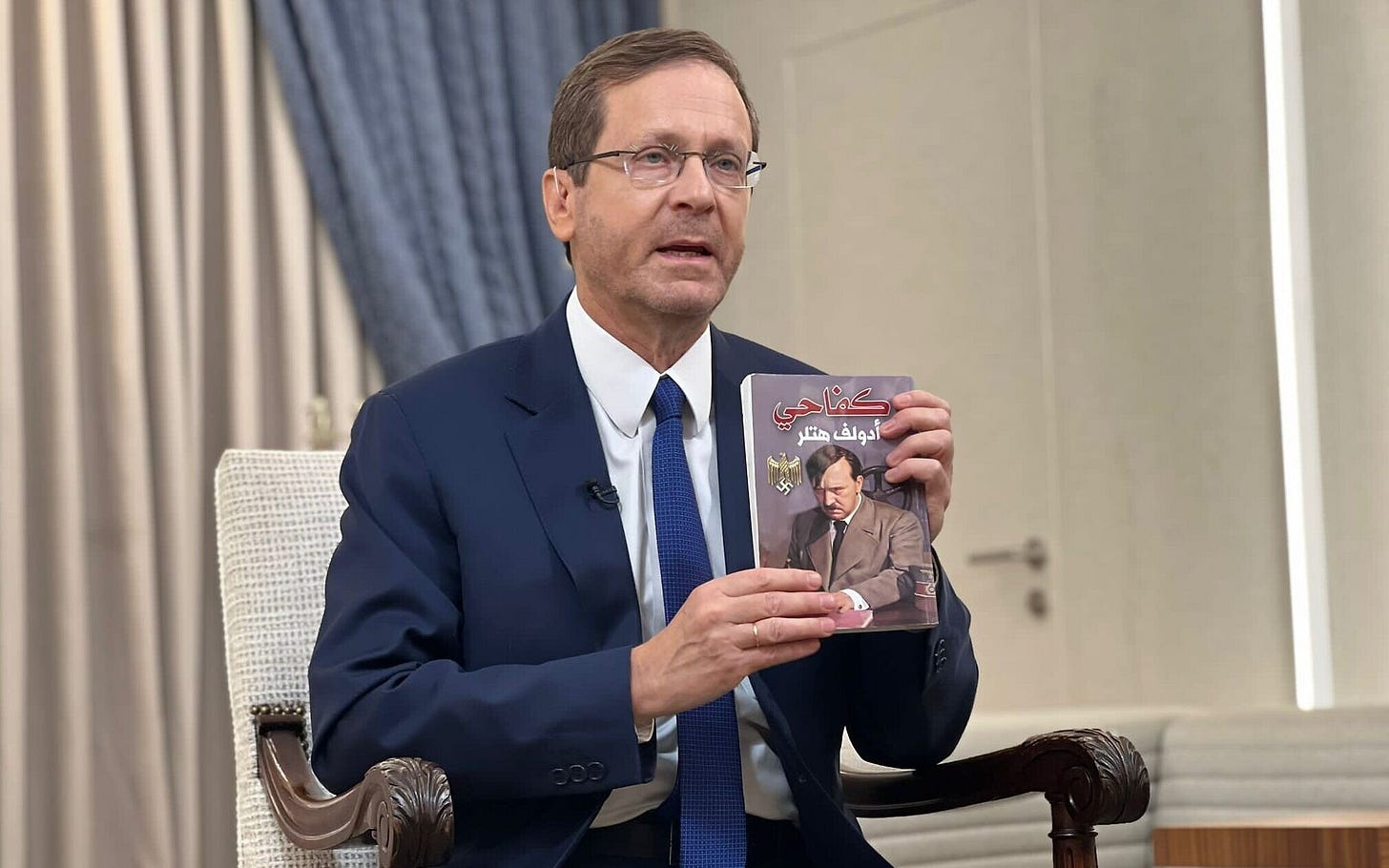

How to deradicalize Gaza from the Islamist brain rot that Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad have indoctrinated into Gaza’s population is a question to which no one yet has a definitive answer.

Germany’s denazification after World War Two is often cited as the model example. But what exactly did it involve, how was it implemented, and did it succeed? It succeeded by some measures, but its approach was incompatible with modern Western sensibilities.

Denazification was aimed at excising the defeated Nazis’ malignant ideology so the country, and Europe, could move on (to fighting the Cold War) — a collision between justice and necessity, vengeance and pedagogy, moral absolutism and geopolitical reality. It was violent, bureaucratic, compromised, and psychologically and morally incomplete.

Denazification formally began with the Potsdam Agreement of August 1945. Its mandate was the eradication of National Socialist ideology from political, legal, economic, cultural, and educational life; the removal of Nazis from positions of authority; the prosecution of major criminals; and the re-education of Germans toward democratic norms. German society was deemed morally contaminated.

These individuals were then brought before more than 500 denazification tribunals, which processed millions of cases. Judges were often German civilians operating under Allied forces oversight, a pragmatic decision born of manpower shortages and linguistic necessity. This would later undermine the process itself.

In the American zone, the early approach was ideological and punitive. Under Joint Chiefs of Staff Directive 1067, the U.S. committed itself to preventing any German recovery that might restore militarism or authoritarianism. Germans were issued rigorous 131-page questionnaires demanding exhaustive disclosure of party membership, institutional affiliations, professional roles, and wartime conduct. The answers were used to sort Germans into five categories: Major Offenders, Offenders, Lesser Offenders, Followers, and Exonerated.

Rarely discussed is that violence was intrinsic to denazification.

The Nuremberg Trials were the most formalized expression of this force. Senior Nazi leaders were tried, convicted and, in some cases, executed. These were symbolic acts as much as legal ones. Evil was named, documented, and destroyed in public view. Nuremberg established enduring precedents — crimes against humanity, crimes against peace — that reshaped international law.

Yet it was also unmistakably victor’s justice. The Allied forces’ bombing campaigns were exempt from scrutiny; Soviet atrocities were excluded altogether. The law was real, but it was not universal.

In popular imagination, the Nuremberg Trials are often associated with justice for the Holocaust. That is not strictly accurate. While many Holocaust perpetrators were indeed prosecuted, the trials’ central purpose was to hold Germany’s leadership accountable for crimes against peace. The Allies sought to prosecute senior Nazis for initiating a war that killed an estimated 80 million people.

While Nuremberg imposed high jurisprudence, rougher legal standards prevailed elsewhere. In the chaotic months following Germany’s collapse, summary executions, beatings, and arbitrary detentions were common. Civilians were marched through concentration camps such as Dachau and Buchenwald, forced to confront crematoria, mass graves, and the residue of industrialized murder. Shock was the pedagogical tool.

The lesson was blunt: This is what was done in your name. Whether it produced shame, rage, or emotional numbness depended on the individual — and, of course, on how deeply invested they had been in the lie.

There was also social and judicial violence. In 1945, Germany was in ruins. Cities lay destroyed, food was scarce, and millions were displaced. Informal retribution flourished. Former Nazis were denounced, assaulted, and sometimes killed. Old grudges resurfaced. Survivors of forced labor and concentration camps occasionally exacted their own justice. This violence was not policy, but the Allies showed literal interest in stopping it.

All Germans were subjected to deradicalization programs that ranged from as few as three weeks to as long as two years for those in sensitive positions such as teachers, civil servants, judges, police, and journalists. Many were temporarily barred from employment. Germans were exposed in gruesome detail to what Germany had done, and it was made clear that the future held little for anyone who refused to renounce Nazism.

Germany’s division into Allied forces zones shaped how deradicalization was conducted. The American zone pursued the most systematic and formal program; the British and French ran shorter, less rigid versions; in the Soviet zone, the process was swift, harsh, and paired with re-indoctrination into communist ideology.

Even this classroom approach involved violence. Some Germans remained defiant, with young men standing up, saluting, and shouting Heil Hitler. The American response was to remove these young men from class, have soldiers beat them with batons, then return them to class, usually without medical attention. The message was clear: Public loyalty to Nazism would neither be tolerated nor yield positive outcomes. It likely changed few minds, but it silenced many — and provided a measure of satisfaction.

Many aspects of denazification worked. The Nazi state was dismantled. Its symbols and organizations were banned and dissolved, and its propaganda destroyed to the point that that it had no immediate public afterlife. Prominent Nazis’ removal through imprisonment, death, or disgrace created space for new political actors. The media was tightly controlled but intentionally pluralized. Newspapers and radio stations were licensed with democratic intent: propaganda for democracy, if you like.

Most importantly, the evidentiary record produced at Nuremberg was unimpeachable. Whatever Germans later told themselves, the regime’s criminality was so thoroughly documented that it could never be erased.

Yet Germans quickly learned to game the system. Germany had been Nazified from top to bottom, so party membership was often framed as a necessity for survival rather than an ideological commitment. The postal clerk who joined the party to keep his job was flattened morally alongside the academic who lent his intellect to racial pseudo-science. The result was not justice but moral equivalence.

Germans acquired official character certificates attesting to anti-Nazi behavior — from sympathetic clergy or neighbors. Nazi conformity and collusion continued to serve them well under Allied forces’ occupation. The process soon descended into farce. Most Germans ended up classified as lowly “followers.” The tribunals became offices of moral minimization, where everyone was a follower and no one responsible for anything. Then geopolitics intervened decisively.

By 1947, Cold War imperatives eclipsed the moral ambitions of 1945. West Germany’s economic recovery became a strategic necessity, requiring administrators, judges, engineers, and doctors — many with Nazi pasts. They were quietly rehabilitated. Amnesty laws were passed. Denazification was wound down, as stability now mattered more than reckoning.

In the Soviet zone, denazification was harsher but equally compromised, with communist indoctrination as the main objective. Minor Nazis were punished publicly; useful ones were absorbed. Loyalty to the new regime replaced moral accountability. The language changed, but authoritarian reflexes remained.

Germans initially responded with resentment, evasion, and self-pity. Denazification was dismissed as victor’s justice. Many Germans cast themselves as victims of Hitler, of war, of bombing, of expulsion. Collective guilt was rejected outright. Responsibility was displaced upward or outward, anywhere but inward. Silence hardened into habit. Families did not speak of the past. Institutions quietly reinstated compromised figures.

The reckoning that mattered — the moral reckoning — came later, and from within. In the 1950s, prosperity anesthetized conscience, but in the 1960s, amid the economic miracle, a new generation revolted against parental silence: Young Germans became old enough to grasp what their parents had done and were repelled.

The Frankfurt Auschwitz trials shattered the fiction that Nazi crimes were abstract or distant. Students demanded answers. Journalists excavated buried histories. Teachers were questioned. Fathers were confronted. The moral labor denazification had failed to complete was taken up, angrily and relentlessly, by a generation that refused to inherit the lie.

Coming to terms with the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung for admirers of absurd German words) was slow, uneven, and deeply painful. Yet much of it was real. Memorials replaced euphemism. Education replaced silence. “Never Again” became constitutional rather than rhetorical. Germany’s moral transformation did not come from Allied questionnaires; it came from a generational revolt against national self-deception.

Yet, this seemingly positive movements has had some unforeseen consequences. Appalled by what their Nazi parents had done, they became early versions of the social justice warriors. They, and especially the generations that followed, took up every imagine just cause — almost prelude to someone such as Greta Thunberg — and for the German Left that included taking up the Palestinian cause, which they did without a hint of irony.

The lessons for Gaza are unavoidable. Germany was not denazified in any meaningful moral sense in 1945. It was defeated, dismantled, and restrained. The ideology collapsed because the state collapsed, having been beaten in war. Conscience came later, and only because a new generation chose to reject inherited falsehoods, and even that was short-lived in some circles where so-called “Palestinianism” became a fashionable cause.

It is fantasy to imagine that Gaza, or Judea and Samaria (also known as the West Bank) at some point, can be deradicalized by administrative fiat, curriculum reform, or externally supervised institutions. Such success has little historical precedent. Ideologies rooted in identity, grievance, and sacred violence fracture only when their moral authority collapses from within.

Denazification was necessary. It broke the Nazi regime and named the crime. It had real successes. Yet it was not sufficient. Conscience cannot be imposed. It must be cultivated unevenly, painfully, and often in rebellion against one’s own family, societal, and cultural inheritance.

The challenge in deradicalizing Palestinians will be that they believe their values are divinely mandated. External actors (Qatar, Turkey, and whatever remains of Iran’s regime) will continue to pump Islamist propaganda into Gaza and Judea and Samaria, sustaining and renewing the sick ideology. With Washington staging signing ceremonies for a Gaza “Board of Peace” that lacks both authority and any credible plan to disarm Hamas or reunify the territory, deradicalization appears to have slipped down the priority list.

Yet the time to begin deradicalization is now. No one should feign surprise when Hamas sympathizers (like their Nazi predecessors) stand defiantly, convinced that God is on their side and that martyrdom awaits them. Nor should anyone be shocked if old American soldier methods return, or if Israel refines them with its customary efficiency — perhaps with practical advice from Arab allies who understand ideological violence far better than Western bureaucrats do.

The world may resemble the 1930s again in many ways. Yet when it comes to deradicalization, it looks uncomfortably like the 1940s as well.

In 1945, the West was led by Churchill, Roosevelt and Truman. Now, the West is led by a collection of Neville Chamberlains.

Israel should conduct its own war crimes trial. While Hamas leaders like Sinwar and Deif were eliminated, put captured Hamas leaders on trial - play the GoPro videos, publicize Hamas documents. Try Lazzirini in absentia as the Allies did with Martin Bormann. Expose UNRWA for being complicit in terror. And, for those who are worried that the world will see these trials as illegitimate or Zionist propaganda, so what. The world bashed Israel for putting Eichmann on trial.

Excellent article, and also addressing some hard truths (ie that the de-Nazification wasn't really completed properly).

One thing to ponder, though, is that at the end of WW2, we had some strong Leaders, REAL Leaders who did not flinch from taking some very strong actions.

Not only do we not possess such Leaders today (except in Israel), but far worse, we have creatures like the UN, the ICC, the ICJ, the EU, the ECHR, UNRWA etc etc.

And we have human rights lawyers.

Additionally, whereas in 1945 and immediately post-war,the indescribable horrors and atrocities of the Holocaust were not disputed, today there is a totally inadequate admission of the 7 October Pogrom - in fact we have some MSM outlets pushing an inversion similar to complaints that might have suggested Rudolf Höss was misunderstood and actually did far more good than harm. Imagine escaped Nazis in Argentina forming a media group publishing material stating everything was the fault of the Jews . . .

I sometimes seriously think that Israel is one of the very few remaining outposts of common sense, let alone genuine morality.