Only in Israel: The Jewish State's Extraordinary Wartime Attributes

“We Jews have a secret weapon in our struggle with the Arabs: We have no place to go.”

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

Share this essay using this link: https://www.futureofjewish.com/p/israel-during-wartime

Wartime Israel is something that I have never experienced, now living here since 2013.

That said, I have never experienced another country in wartime, except the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that did not feel like wartime at all in mainland America. (I was also a teenager at the time and had no real understanding of war, world history, U.S. domestic politics, the Middle East, geopolitics, and so forth.)

Here in Israel, these days, most Israelis that I have spoken with are living with day-to-day cognitive and emotional dissonance — on one hand, trying to go about our lives and taking care of our core responsibilities like virtually every other adult across the world.

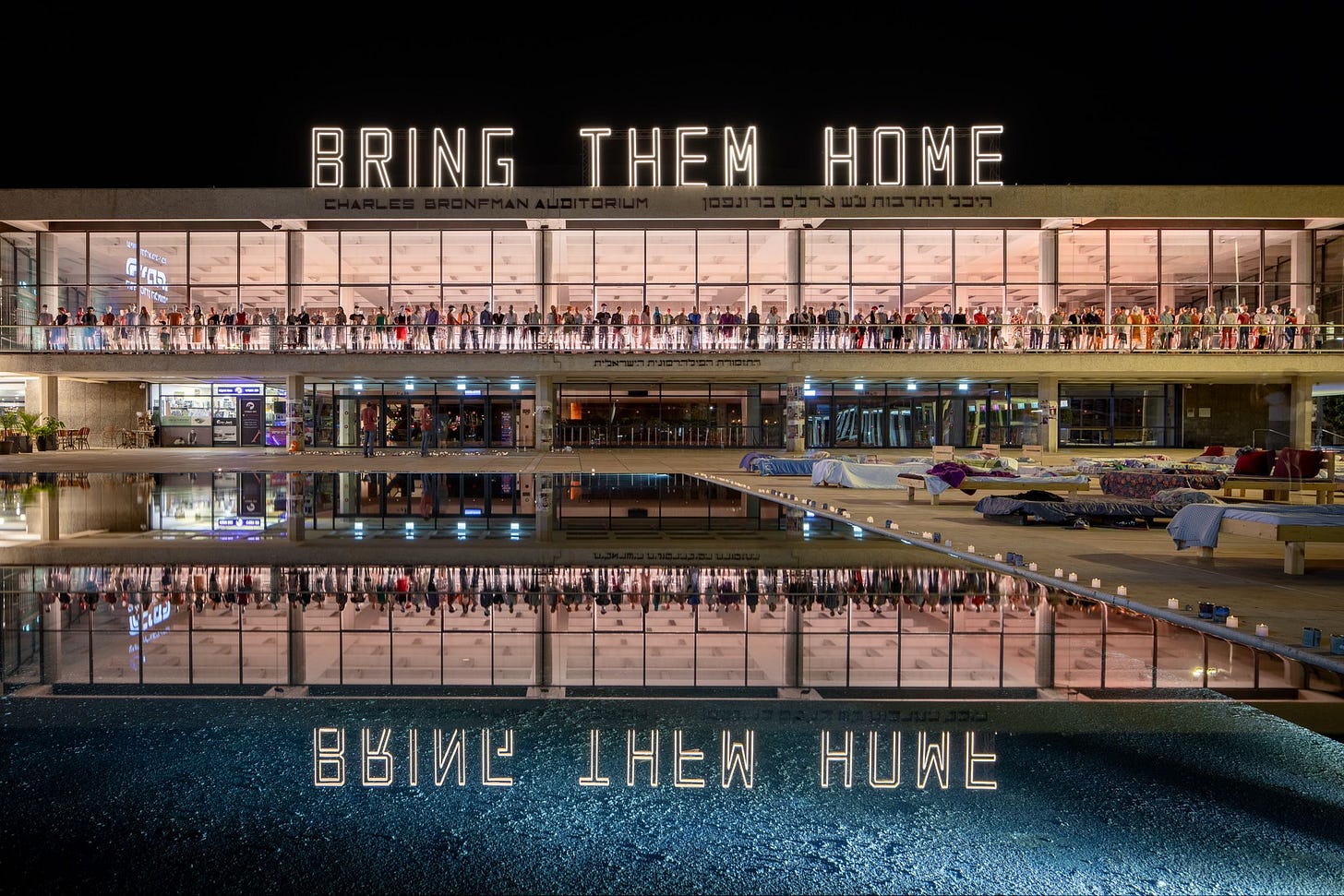

And on the other hand, constantly being reminded that we are in an existential war against Iran and Qatar (via Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and Hezbollah) and that our hostages are (still!!) in Gaza, not all of them alive unfortunately.

As I write this at a café in Tel Aviv, an older soldier in full uniform and his firearm wrapped around his body just walked by, holding three supermarket bags overpacked with clothes — probably on his way to donate them to families who have been evacuated from their homes on the borders with Gaza and Lebanon.

He will then head to one of the IDF’s bases, possibly the headquarters here in Tel Aviv, where as a full-time reservist he is tasked with putting on his “Save the Jewish State” hat, before returning home presumably to his wife and young children whose lives were upended when their husband and father was suddenly called up shortly after October 7th.

You do not need to worry about this and other Israeli soldiers — at least not from a financial standpoint. When the IDF calls up reservists, the army pays for 100-percent of each soldier’s salary; meaning, if a reservist earns a million-dollar salary, the IDF fully pays it (by reimbursing the employer) as long as the soldier is active in reserves. Thus, the IDF must calculate these costs into the overall budget when deciding which reservists to call upon and which to not.

However, life is not just about finances. People have careers, responsibilities, commitments, aspirations, and so forth. To ask people in their 30s and even 40s to effectively pause their life for a war that no one saw coming is a cumbersome transition, emotionally and psychologically, in both directions: from civilian life to reservist life and back to civilian life. And I am not even talking about the many combat reservists who will return to “regular life” with PTSD.

You will rarely hear Israelis complain about this reality, but it certainly weighs on them, their families, and others in their lives. For example, one of my good friends works at a successful startup that employs 20 people — 60 percent of whom were called up to reserves after October 7th, including all the founders. Imagine the risk that this poses to the employees (who depend on the company for income) and their families, as well as to the investors (most of whom are not Israeli).

The point I am trying to make is that, we should not just take for granted Israelis’ extraordinary courage and desire to defend our homeland while putting much of their lives on hold. There are beyond-significant “prices” that many of them are paying now and will have to pay in the future.

A few days ago, I walked into one of the stores of Israel’s most popular ice cream chain, Golda. As I browsed the 20 or so flavors, one ice cream flavor — in Israel’s blue and white colors — was called “Am Yisrael Chai,” crafted in light of October 7th.

The container directly below it was even more striking — because it was empty, on purpose, with the word in Hebrew and English, “missing,” in honor of the hostages.

I know one of the hostages’ father: Jon Polin, whose son is the American-Israeli hostage, Hirsh Goldberg-Polin. A few months before October 7th, Jon and I met in Tel Aviv to discuss ways in which we could collaborate on Zionism-related projects, since he also works in the field.

What’s more, a few weeks before the Hamas-led massacres some eight months ago, I went on a date with one of the women who was either killed on October 7th at the Nova Music Festival, or abducted back to Gaza. Her fate is still unclear to me. Apparently she went to the festival with her sister.

I know this because, a few days after October 7th, I saw a photo of a women on a “missing” poster who looked incredibly similar to the women with whom I went on that date, but I could not put two and two together. A few weeks later, I realized that it was the women’s sister, and that the two had attended the Nova Music Festival together.

I am telling you these stories to illustrate just how small of a country Israel is; everyone knows someone who has been directly affected by October 7th and the subsequent Israel-Hamas war.

I also have several friends in reserves, like everyone else here. I play basketball at a park here in Tel Aviv with two brothers, Shaked and Gal. Shaked is in his late 20s and was not called up to reserves; his brother Gal is 23 and had recently finished his regular army service in a paratroopers unit prior to October 7th.

Gal was called back for reserve duty and has been in Gaza since November; about a week ago, he received an official notice from the military that his unit will likely be needed “in Lebanon” it said.

His brother Shaked told me that it is unclear if “in Lebanon” means on the Israeli side of the border with Lebanon, where many IDF troops have been stationed since October 7th, or in Lebanon itself, which means a war with Hezbollah whose arsenal and number of forces are far greater than that of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza.

Every few weeks I text Shaked to check up on Gal, and every time the media publishes another fallen Israeli soldier, I nervously check to make sure it is not Gal — a common practice among millions of Israelis. The vast majority of us know someone who is on the literal front lines.

When the U.S. invaded Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003, respectively, I was in my early teenage years, living in Los Angeles. I remember that it was a big deal in America, but I do not recall many adults around me discussing the specific strategies and tactics of these wars.

In Israel, every adult seems to think that they know better than the prime minister and IDF chief of staff. You enter a taxi and the driver gives you a detailed breakdown of everything our leadership is doing right — but mostly wrong — during the 25-minute ride, and precisely how he would do it differently (and, of course, better).

You walk by a restaurant in Tel Aviv and hear a group of Israelis passionately debating what the “day after” should look like in Gaza. As they say: two Jews, three opinions, sometimes even four.

Most Israelis are incredibly engaged in the sociopolitical issues of our country. My Israeli cousin, who is in his 70s and is one of the smartest people I know, talks about Benjamin Netanyahu and other Israeli politicians as if he knows them personally, an M.O. amongst many Israelis.

This likely stems from the Israeli saying and cultural attribute, beh’govah einayim in Hebrew, which directly translates to: “at eye level.” Effectively this means that Israelis perceive each other as equals, regardless of profession, status, socioeconomics, et cetera. Israelis do not “look up” to politicians, celebrities, and other public figures. They see them as mere equals.

Israeli humor, which was already plenty cynical, sarcastic, dark, and self-deprecating before October 7th, is even more of these characteristics nowadays — poking fun at politicians, government policies, and sociopolitical issues in the most politically incorrect ways, while holding nothing back.

One comedian started her standup bit by asking if there were any Americans and Canadians in the audience. She then told a joke about how people who simultaneously support Hamas and obsess about their pronouns would manage in Gaza — and then added, “That’s why I asked if there are any Americans and Canadians in the crowd. It’s okay. You can laugh. This is Israel, not America or Canada. Making fun of people’s pronouns is still not a hate crime here.”

Other comedians joke about how much they are able to get done in the 90 seconds that people in central Israel have to get to a bomb shelter after hearing an incoming rocket siren (compared to 10 or 15 seconds on Israel-Gaza border towns); how they need to fake a non-Israeli accent when they are abroad and get into an Uber with an Arab driver; and how other standup comedians merely complain about drunk hecklers in the crowd during their shows, while Israeli comedians have to deal with 300 rockets from Iran during theirs.

This humor is not for everyone; indeed, Israel is not for everyone, but such humor is sort of a coping mechanism to deal with various challenges, both internally and externally.

There is also the not-so-sexy sides of Israel during wartime, especially these days. Many people do not trust our government, and I am not just talking about “leftists.” I know many centrists and right-wing folks who have had enough with Netanyahu.

Certainly, in any given country, people not trusting their government during wartime is nothing new, but Israel is such a tiny country that you feel the government every single day.

In light of this widespread mistrust, the Israeli society is essentially running several domestic aspects of the country through a combination of private sector and nonprofit work, volunteers, and donations. It is truly a remarkable sight to see; instead of finger-pointing at government officials and shouting “Shame on you!” Israelis have taken the situation into their own hands and made the best of the worst.

Still, many Israelis continue to live with bothersome trauma, and I am not just talking about the ones who have been directly affected by the October 7th massacres and soldiers on the front lines. Virtually every Israeli is dealing with what we can call “micro-traumas” — and they cause us to have crazy thoughts which come at random times. Like when you are on a date at a wine bar with a women and suddenly you start wondering what you would do to save her if a terrorist walked in and started opening fire.

At first, I thought it was me. I tend to worry. But then I heard Israeli journalist and news anchor Lucy Aharish say she contemplates hiding her child in the washing machine if a terrorist was to infiltrate her Tel Aviv apartment. Someone else detailed what household items could make for good weapons (e.g. a hot iron).

Another thought I keep having, especially when I am in a bad or unbecoming mood, is that I could have been one of the hostages. After all, I was sleeping just 75 kilometers away from the Gaza border on October 7th. So I remind myself that I am incredibly fortunate to be where I am today — in other words, not in an Islamist underground hostage chamber in Gaza — and this reminder quickly snaps me out of my subpar mood. I have no doubt that many Israelis feel the same.

There is also tremendous fear that hovers over all of minuscule Israel; after all, we have overwhelmingly cruel and grossly antisemitic enemies on all of our borders. Writing this in Tel Aviv (the center of Israel), I am less than 30 kilometers from the West Bank, 140 kilometers from Lebanon, and 75 kilometers from Gaza. Hezbollah in Lebanon could deal a lethal blow to Israel at moment’s notice, and Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza could keep part of the IDF occupied down there in order to maximize Hezbollah’s impact.

Even worse, Hezbollah, Hamas, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad are terror groups, not countries, that are purposely embedded into civilian populations and infrastructure. Thus, it is an asymmetrical war that ultimately makes Israel look bad for no good reason and generates unsubstantiated international pressure on the Jewish state to curtail its response, thus limiting deterrence and inevitably making these horrific attacks all the more common.

You can drive yourself crazy thinking about all the disastrous scenarios in which Israel’s future is grim, no less the internal turmoil between so-called “Jewish Israelis” (who prefer Judaism over democracy) and “Israeli Jews” (who prefer liberalism over Judaism).

But just like the Palestinians and Arabs are divided amongst themselves but united about their hate for Israel and Jews, Israelis are united against those who want to destroy us, and we are not afraid to put up a fight.

It is in these moments of overpowering psychological and emotional anguish that I remind myself of this fact, as well as of a few legendary quotes from former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, who said:

“We’re not the only people in the world who’ve had difficulties with neighbors; that has happened to many. We are the only country in the world whose neighbors do not say, ‘We are going to war because we want a certain piece of land from Israel,’ or waterways or anything of that kind. We’re the only people in the world where our neighbors openly announce they just won’t have us here. And they will not give up fighting and they will not give up war as long as we remain alive. Here.”

“So this is the crux of the problem: It isn’t anything concrete that they want from us. That’s why it doesn’t make sense when people say, ‘Give up this and give up the other place. Give up the Golan Heights,’ for instance.”

“What happened when we were not on the Golan Heights? We were not on the Golan Heights before 1967, and for 19 years, Syria had guns up there and shot at our agricultural settlements below. We were not on the Golan Heights! So what, if we give up the Golan Heights, they will stop shooting? We were not in the Suez Canal when the war started.”

“It’s because [the Arabs] refuse to acquiesce to our existence. Therefore there can be no compromise. They say we must be dead. And we say we want to be alive. Between life and death, I don’t know of a compromise.”

And then she added another zinger: “We Jews have a secret weapon in our struggle with the Arabs: We have no place to go.”

Well written and very true. As an Ex-Rhodesian I can, along with many others who were forced from our country and watch it get destroyed,

I partially understand what Israel is going through, but in a much bigger way. I pray for you all.

Keep up the good work Cape Town

Great piece. We never read about the Israelis displaced in the North. My daughter- in- law's Mom was living at the beautiful Rosh Hanikra kibbutz. After the 10/7 massacre she's been staying with different relatives.