The Day the New York Times Died

This past Christmas Eve, the New York Times went to a place I’d never imagine: It published an essay by Gaza City’s mayor, an appointee of Hamas. You know, the world-renowned terrorist group.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free and zero-advertising for all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

In 2020, U.S. senator Tom Cotton wrote an opinion piece for the New York Times, encouraging the federal government to deploy military personnel to assist law enforcement with riots that seemed to be getting out of control in New York City and St. Louis.

Cotton pointed out that U.S. presidents have exercised this authority on dozens of occasions to protect law-abiding citizens from disorder, so he was not making some precedent-making claim.

“After publication, this essay met strong criticism from many readers (and many Times colleagues), we have concluded that the essay fell short of our standards and should not have been published,” the newspaper said. “Finally, we failed to offer appropriate additional context — either in the text or the presentation — that could have helped readers within a larger framework of debate.”

Fair, I guess.

But then, on Christmas Eve just a few days ago, the New York Times went to a place I’d never honestly imagine: It published an op-ed by Gaza City’s mayor, an appointee of Hamas. You know, the world-renowned terrorist group.

Publishing the views of a democratically elected politician went too far for the Times and its readers, but platforming Gaza City’s mayor, who was appointed by an atrocious terror organization, is perfectly fine. Understood.

Gaza City’s mayor, Yahya Al-Sarraj, started out his essay by talking about “the intricately designed Rashad al-Shawa Cultural Center in Gaza City,” which is now “rubble” because it was “destroyed by Israeli bombardment.”

I guess I missed the “appropriate additional context” — that the mayor’s bosses in Hamas belligerently started this war. And I suppose it was too much to think the Times was genuinely interested in helping readers “within a larger framework of debate.”

Scott Johnson, an American attorney, questioned the legality of Sarraj’s essay, writing: “As the Hamas-appointed mayor of Gaza City, Sarraj must be a senior official of a foreign terrorist organization designated as such since 1997 pursuant to United States law. Accordingly, it’s illegal for Americans to render material assistance to it.”1

Why would such a reputable company take such an irresponsible risk?

It turns out, the New York Times is not who they want us to think they are.

“Times readers are being served a very restricted range of views, some of them presented as straight news by a publication that still holds itself out as independent of any politics,” according to James Bennet, a former editor at the Times. “The paper leads its readers further into the trap of thinking that what they are reading is independent and impartial — and this misleads them about their country’s center of political and cultural gravity.”2

Throughout the Israel-Hamas war, the New York Times has continued to give Hamas a dangerous platform, which the newspaper defends as important to shed more light, not less, on the most extreme corners of the world. But less light is what readers get.

Sympathetic reporting about Hamas is becoming more common. Influential left-wing columnists and editors coax reporters into interviewing Hamas operatives and come away suckered into thinking there is something else besides genocidal ideology that could explain their perversions.

“The Hamas leaders and spokesmen who agreed to our interviews were rarely what you would expect of representatives of a terrorist organization,” according to journalist Ilene Prusher. “They were men who were fluent in English, logical-sounding about their grievances, and highly educated to boot, usually in engineering or medicine. They portrayed themselves as part of a ‘political wing’ of Hamas, one that was unaware of what was being planned by the more secretive military wing. Often, these spokesman insisted, they had no idea that an attack was imminent.”3

Of course, you’d have to be an idiot to not tell the difference between “political” Hamas and “military” Hamas. It’s just manipulative linguistic gymnastics that the organization consciously created for the purpose of deception.

“By and large, we reporters ate it up,” wrote Prusher. “Our editors wanted us to have access to this shadowy group and to explain its lure for average Palestinians. By claiming that the organization’s left hand didn’t know what the right hand was doing, Hamas made it easy for themselves to evade tough questions — like, why target civilians rather than military targets? — and convenient for so many of us to feel like we were putting our fingers on the Palestinian pulse rather than sitting down for tea with terrorists.”

Hamas talks the talk. “Look, we take no joy in seeing Israeli civilians get blown up,” said one spokesman — back in the day when Hamas’ worst weapon was a suicide bomber in an urban area — before going on to insist that these attacks were the only rational answer to what they saw as Israel occupying Palestinian territories.

When Prusher asked why Hamas wouldn’t take a crack at negotiations instead, they responded that there was no point in talking to Israel — and Israel wasn’t exactly jumping to talk to Hamas either. The spokesman insisted that she not use his name with that almost-empathetic quote about not taking joy in killing Israelis, probably because he knew it sounded good to the Western ear.

Yet the issue is not Hamas; it’s the media outlets whose obvious biases against Israel allow the terror group to easily play games with reporters. During the first major Israel-Hamas conflict in 2008 to 2009, for example, Hamas said that fewer than 50 of the 1,400 dead in Gaza had been combatants. But more than a year later, Hamas’ interior minister acknowledged in an interview with the London-based Al-Hayat newspaper that between 600 and 700 of its militants were killed in that war.

Why are reporters so gullible? And how could outlets like the venerable New York Times not be more transparent about how they don’t have independent verification and provide context on how unreliable Hamas has proved to be in the past? I mean, it is, after all, a terrorist organization, remember?

From my analysis, there are two predominant explanations: a distorted organizational culture and repugnant corporate greed.

More than 30 years ago, a young reporter named Todd Purdum nervously asked a New York Times all-staff meeting what would be done about the “climate of fear” within the newsroom in which reporters felt intimidated by their bosses.

“The moment immediately entered Times lore,” according to James Bennet. “There is a lot not to miss about the days when editors could strike terror in young reporters like me and Purdum. But the pendulum has swung so far in the other direction that editors now tremble before their reporters and even their interns.”

Yes, even their interns. Some might call this “soft” — but it gets worse. When the Tom Cotton op-ed was published, the New York Times union issued a statement purporting “a clear threat to the health and safety of the journalists we represent.” Turns out, management had been expecting for some time that the union would seek a voice in editorial decision-making, and some thought this was the moment that the union was making its move.

What’s more, the Times experienced its largest sick day in history; people were turning down job offers because of the Cotton op-ed, and some people were quitting. The newspaper’s publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr., demanded that Bennet, the editorials page editor responsible for publishing the Cotton piece, resign.

“The Times’ problem has metastasized from liberal bias to illiberal bias, from an inclination to favor one side of the national debate to an impulse to shut debate down altogether,” wrote Bennet. “All the empathy and humility in the world will not mean much against the pressures of intolerance and tribalism without an invaluable quality: courage … the moral and intellectual courage to take the other side seriously and to report truths and ideas that your own side demonizes for fear they will harm its cause.”

Bari Weiss, an opinion writer and editor at the New York Times during this time, which coincided with Donald Trump’s U.S. presidency, said the lessons that ought to have followed his election — “lessons about the importance of understanding other Americans, the necessity of resisting tribalism, and the centrality of the free exchange of ideas to a democratic society” — were not learned.

“Instead, a new consensus has emerged in the press, but perhaps especially at this paper: that truth isn’t a process of collective discovery, but an orthodoxy already known to an enlightened few whose job is to inform everyone else,” wrote Weiss.4

One of the splendors of embracing illiberalism is that you are, by default, right about everything, so you feel endlessly justified in shouting down disagreement. And this is one of the reasons why the New York Times’ leadership is losing control of its principles.

Since Adolph Ochs bought the newspaper in 1896, the Times has said that it does journalism “without fear or favor,” and Ochs himself aimed “to make of the columns of the New York Times a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion.”

Neither of these ambitions can be remotely true today, not when it gives a Hamas-appointed mayor their platform. But maybe this is all by design. Maybe the New York Times’ quasi-journalism is actually good for its bottom line, more so than what some in the media industry call its “reputation for thoroughness.”

In early 2009, speculation swirled that The New York Times might go bankrupt. Earnings reports released by the company just a few months prior indicated that drastic measures would have to be taken over the next several months, or the paper would default on some $400 million in debt. With more than $1 billion in debt already, only $46 million in cash reserves, and no clear path to tap into capital markets, the newspaper’s future was frail.

But it survived, hiring Mark Thompson as president and CEO to oversee a dramatic transformation of the storied institution into a digital-centric news brand. The biggest flashing red light when he arrived was the rate at which the company was losing digital subscribers. It was something like 74,000 in his first quarter, the last quarter of 2012. By the second quarter of 2013, it was 22,000 or 23,000.5

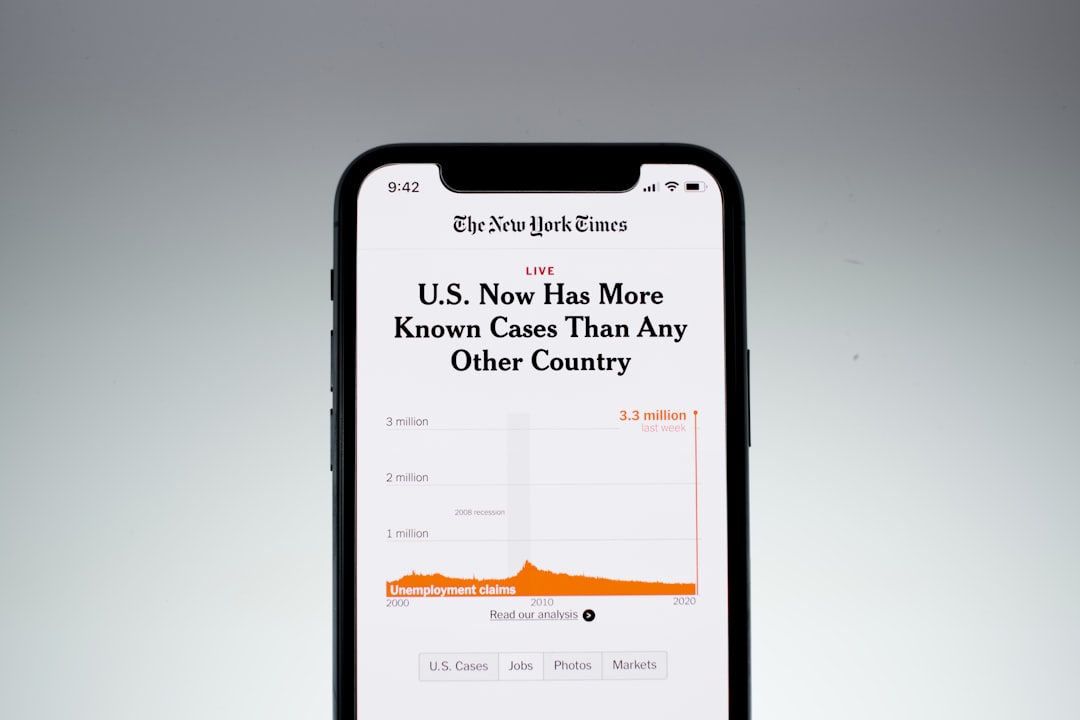

How, then, did the New York Times go from knocking on bankruptcy’s door, to more than seven million paying subscribers by 2020? Three words: “the Trump bump.”

Despite endorsing Hillary Clinton during the 2016 U.S. presidential race, the New York Times’ paid subscriptions online and in print soared since Election Day of that year.6 Even Leslie Moonves, CEO of CBS, said about Trump’s candidacy: “It may not be good for America, but it is very good for CBS.”

During the four years of Trump’s presidency, the newspaper added a whopping five million subscribers or so. But subscribers were not just buying the New York Times’ vaunted brand. They were buying what the newspaper’s writers and guest writers were saying, and how they were saying it. While journalists think people want accuracy and impartiality, polls suggest that, actually, most of us are seeking affirmation.7

According to James Bennet, the Times’ Opinion department was historically a relic of the era when it drew and enforced a line between news and opinion journalism. Editors in the newsroom did not touch opinionated copy, and opinion journalists and editors kept largely to their own, distant floor within the company’s building. Such attention to detail could seem excessive, but it enforced a principle that reporters ought to make a relentless effort against bias in the news.

By 2016, more opinion columnists and critics were writing for the newsroom than for Opinion. Just like at cable news networks, the guard-rails between commentary and news were disappearing, and readers had little reason to trust that New York Times journalists were resisting rather than indulging their biases.

The outlet’s newsroom had added more cultural critics, and, as executive editor Dean Baquet noted, they were free to opine about politics. Departments across the newsroom had also begun appointing their own “columnists,” without stipulating any rules that might distinguish them from columnists in Opinion.

Unsurprisingly, the internet rewards opinionated work and, as news editors felt increasing pressure to generate more paid subscriptions and page views, they began not just hiring more opinion writers, but also running their own versions of opinionated essays by outside voices — historically, the territory of Opinion’s op-ed department.

Yet because the paper continued to honor its old principles, none of this work could be labelled “opinion.” (It still isn’t.) After all, it did not come from the Opinion department. And so a columnist might call for, say, the U.S. to give Israel “tough love,” as one did, or an outside writer might argue that we must embrace Palestinian statehood now, immediately after Hamas’ unconscionable massacre, as one did, and to the average reader their work would appear indistinguishable from the Times’ news articles.

“The newsroom’s embrace of opinion journalism has compromised the Times’ independence, misled its readers, and fostered a culture of intolerance and conformity,” wrote Bennet.

By similarly circular logic, the newsroom’s opinion journalism breaks another of the newspaper’s commitments to its readers. Because the newsroom officially does not do opinion — even though it openly hires and publishes opinion journalists — it feels free to ignore Opinion’s mandate to provide a diversity of views.

Bennet urged the newspaper’s leadership several times to add a conservative to the newsroom roster of cultural critics, which would serve the readers by diversifying the Times’ analysis of culture, where the paper’s left-wing bias had become most blatant, and it would show that the newsroom also believed in restoring the Times’ commitment to taking conservatives seriously. Management said this was a good idea, but never acted on it.

Bennet also tried out the idea on one of the newspaper’s top cultural editors, who said he didn’t think Times readers “would be interested in that point of view,” according to Bennet.

Bari Weiss also had something to say about this: “Stories are chosen and told in a way to satisfy the narrowest of audiences, rather than to allow a curious public to read about the world and then draw their own conclusions.”

As the Times tried to compete for more readers online, unvaried opinion was spreading through the newsroom in other ways. News desks were urging reporters to write in the first person and to use more “voice,” but few newsroom editors had experience in managing this kind of journalism, and no one seemed to know where “voice” stopped and “opinion” started. The Times magazine, meanwhile, “became a crusading progressive publication,” according to Bennet.

For all she could, Weiss attempted to buck the organization’s warped culture, which she said made her the subject of constant bullying by colleagues who disagreed with her views. Weiss said they called her a Nazi and a racist, while making comments about how she was “writing about the Jews again.”

“Several colleagues perceived to be friendly with me were badgered by coworkers,” wrote Weiss. “My work and my character were openly demeaned on company-wide Slack channels where masthead editors regularly weigh in. There, some coworkers insisted I need to be rooted out if this company is to be a truly ‘inclusive’ one, while others posted ax emojis next to my name. Still other New York Times employees publicly smeared me as a liar and a bigot on Twitter with no fear that harassing me will be met with appropriate action. They never were.”

It might be worth mentioning that the New York Times could learn a thing or two from the Wall Street Journal, which has kept its journalistic poise and maintained a tighter separation between its news and opinion journalism, thus protecting the integrity of its work.

After Bennet was chased out of his job at the Times, Wall Street Journal reporters and other staff attempted a similar assault on their Opinion department. Some 280 of them signed a letter listing pieces they found offensive and demanding changes in how their Opinion colleagues approached their work.

“Their anxieties aren’t our responsibility,” wrote the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board in a note to readers after the letter was leaked. “The signers report to the news editors or other parts of the business.”

The editorial board then clarified its position, just to make sure everyone got the point: “We are not the New York Times.”

“THE MIRAGE OF YAHYA SARRAJ.” Power Line.

“When the New York Times lost its way.” The Economist.

“Opinion: I reported on Hamas in Gaza for over a decade. Here are the questions I’m asking myself now.” CNN.

“Resignation Letter.” Bari Weiss.

“Building a digital New York Times: CEO Mark Thompson.” McKinsey & Company.

“Trump era pushes NYT to new heights.” Axios.

“‘Trust’ in the News Media Has Come to Mean Affirmation.” The New York Times.

Been dead since 2016 - You are just now noticing the stench.

As one of your older readers I can say that articles about Israel have been quite biased in the NY Times going back a long way. Also remember that they cheer led us into Iraq with so called factual articles. Anyway, great as usual and yes, I now read the Wall Street Journal.