The Greatest Decolonization Project on Planet Earth

Colonization is a term that tends to pop up often in conversations about Israel. Let's explore it further.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

When we misinterpret words, we misinterpret each other, and we misinterpret much of the world.

Such is the case with the word “decolonization,” defined as the undoing of colonialism, whereby imperial powers establish and dominate foreign territories.

The United Nations states that the fundamental right to self-determination is the core requirement for decolonization.

Nikki Sanchez, an indigenous academic, contends that decolonization requires pushing back on historical amnesia, a phenomenon by which settlers choose not to recognize the genocidal role of colonialism.1 (Did someone say Hamas?)

She also emphasizes indigenous peoples’ history and their continued resilience against erasure, extraction, and oppression. (Sounds a lot like Jewish history, doesn’t it?)

As with many terms that are hash-tagged, commercialized, and weaponized, decolonization has been distorted and casually thrown around online, in academic discourse, by the media, and across so-called social justice spaces. This causes people to either dismiss the term entirely, or engage with it in a way that displaces indigenous narratives so central to their movements.

Such is the story of the Jewish People, which for 2,000 years was continuously subject to the aforementioned erasure, extraction, and oppression virtually wherever our predecessors went. Yet for these 2,000 years, since the fall of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, we’ve been yearning to return to the Land of Israel, our obvious indigenous homeland.

Hence why this 2,000-year Jewish dream is explicitly embedded into the Israeli national anthem “HaTikva,” which was adopted from a poem written in 1878 (two decades before the First Zionist Congress convened, and 70 years before the State of Israel was founded).

“Our hope is not yet lost, the hope of two thousand years,” the anthem’s lyrics go, “to be a free nation in our own land, the land of Zion and Jerusalem.”

Call it a coincidence? I think not.

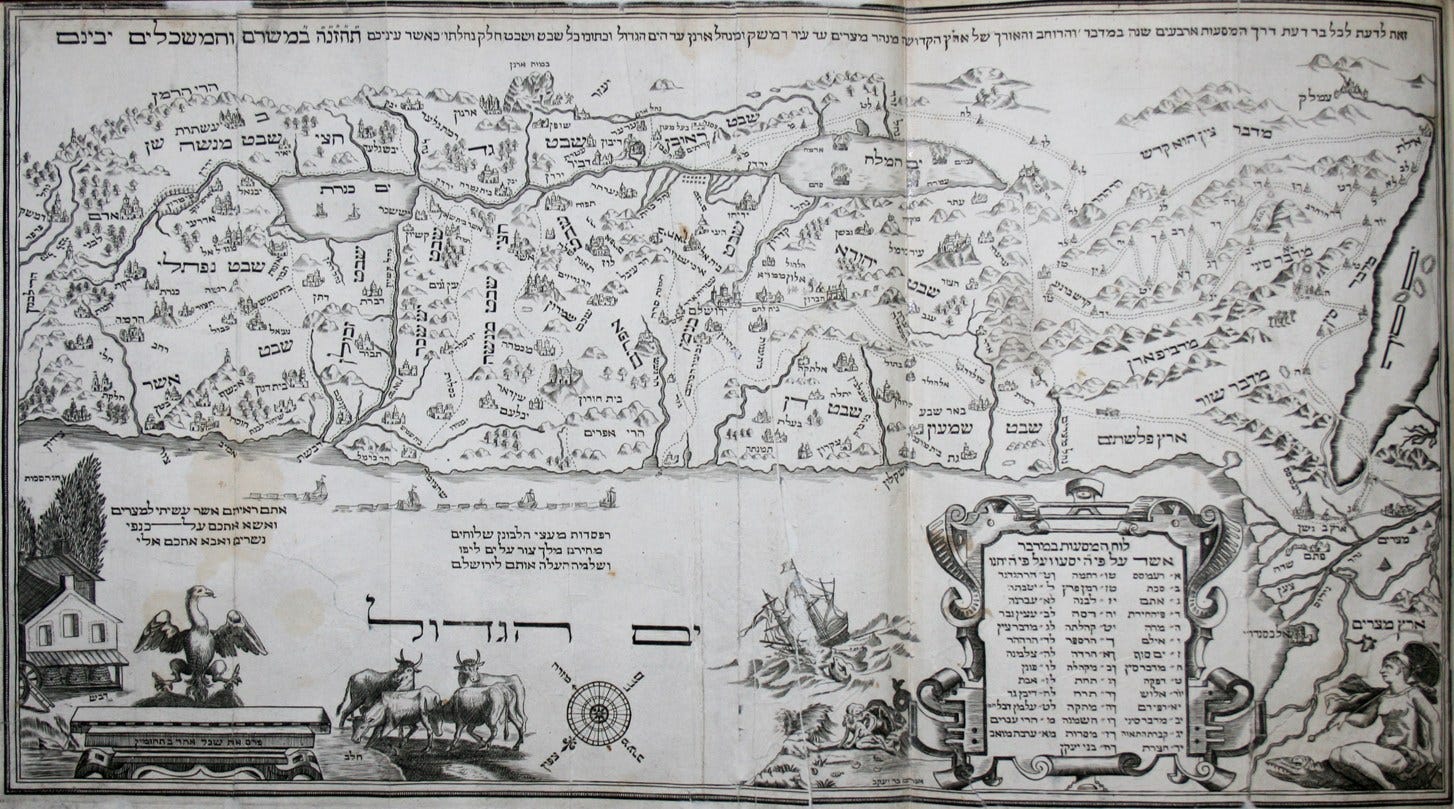

We know as a matter of fact that the birthplace of the Jewish People is called the Land of Israel (in Hebrew: Eretz Yisrael). There, a significant part of our nation’s long history was enacted, of which the first thousand years are recorded in the Hebrew Bible.

Moreover, the Jewish People’s cultural, religious, and national identities were formed in the Land of Israel; and there, our physical presence has been maintained through the centuries, even after the Jewish majority was forced into exile.

During the many years of dispersion, the Jewish People never severed nor forgot its bond with the Land. After all, an enormous amount of archeological research clearly reveals the historical link between the Jewish People, the Hebrew Bible, and the Land of Israel.

It all started with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob — patriarchs of the Jewish People — who settled in the Land of Israel. Famine forced them, the Israelites, to migrate to Egypt. Moses eventually led the Israelites back to Israel, after 40 years of wandering in the desert. The joke is that, with all due respect to Moses, he led us back to the only place in the Middle East that doesn’t have oil.

Historical records testify to the existence of Hebrew from the 10th century BCE to the late Second Temple period, after which the language developed into Mishnaic Hebrew. From about the sixth century BCE until the Middle Ages, many Jews spoke Aramaic, a related Semitic language.

Circa 1020 BCE, the first Jewish monarchy was established by King Saul, and King David made Jerusalem our capital just 20 years later. A few decades down the round, King Solomon built the First Temple, the Jewish People’s national and spiritual center.

But then the Jews did what we do best: They started arguing, and the kingdom was divided into two, Judah and Israel. Significantly weaker as a result, the Assyrians crushed the Jewish populace and 10 tribes were expelled, which is how “the 10 Lost Tribes of Israel” originated. Eventually, the First Temple was also destroyed and most Jews were exiled.

Some 50 years later, many Jews returned from Babylonia and rebuilt the temple, known as the Second Temple. After a couple of centuries, land in Israel was conquered by Alexander the Great, and Hellenistic rule ensued. Jews known as the Maccabees revolted against restrictions on Jewish practices and desecration of our temple, leading to Jewish independence — until the Romans arrived and subsequently ruled the Land of Israel.

Again, the Jews revolted, which led to the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple, the last stand of the Jews at Masada, and the Bar Kokhba uprising. According to Josephus, a Roman-Jewish historian and military leader, over a million non-combatants Jews died, and tens of thousands were enslaved.

While a minority of Jews have lived in and around Jerusalem since then, this watershed moment, the Second Temple’s destruction — the elimination of the symbolic center of Judaism and Jewish identity — motivated many Jews to formulate a new self-definition and adjust their existence to the prospect of an indefinite period of displacement.

During the Middle Ages, due to increasing migration and resettlement, Jews divided into distinct regional groups which today are generally addressed according to two primary geographical groupings: the Ashkenazi of Northern and Eastern Europe, and the Sephardic Jews of Iberia (Spain and Portugal), North Africa, and the Middle East.

From the 2nd century CE until the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language circa 1880, Hebrew served as a literary rabbinic language and as the Jewish language of prayer. After the spoken usage of Mishnaic Hebrew ended in the second century CE, Hebrew had not been spoken as a mother tongue.

Meanwhile, in the the Land of Israel, foreign domination endured, including by the Byzantines, the Arabs, the Crusaders, the Mamluks, the Ottomans, and the British.

But if we go back to the second millennium BCE, we know that modern-day Israel was inhabited by the Canaanites, Semitic-speaking peoples who practiced the Canaanite religion. The Israelites (who became the Jews) emerged later as a separate ethno-religious group in the region, and Jews eventually formed the majority of the population during classical antiquity.

In the centuries that followed, the region experienced political and economic unrest, mass conversions to Christianity (and subsequent Christianization of the Roman Empire), as well as the religious persecution of minorities. The Jewish emigration and Christian immigration — as well as the conversion of pagans, Jews, and Samaritans — contributed to a Christian majority forming in Late Roman and Byzantine eras.

In the seventh century, the Arab Rashiduns conquered the Muslim conquest of the Levant; they were later succeeded by other Arabic-speaking Muslim dynasties, including the Umayyads, Abbasids, and the Fatimids. During the next several centuries, the population of Palestine (formerly the Land of Israel) drastically decreased, from an estimated one million during the Roman and Byzantine periods, to about 300,000 by the early Ottoman period (the early 16th century).

Over time, much of the existing population adopted Arab culture and language and converted to Islam. Hence, the region was not originally Arab. Its Arabization was a consequence of the gradual inclusion of Palestine within the rapidly expanding Islamic Caliphates established by Arabian tribes and their local allies.

The settlement of Arabs before and after the Muslim conquest is thought to have played a role in accelerating the Islamization process. Some scholars suggest that by the arrival of the Crusaders, Palestine was already overwhelmingly Muslim, while others claim it was only after the Crusades that the Christians lost their majority, and that the process of mass Islamization took place much later, perhaps during the Mamluk period (from the mid-13th to early-16th centuries).

For several centuries during the Ottoman period, the population in Palestine declined and fluctuated between 150,000 and 250,000 inhabitants, and it was only in the 19th century that rapid population growth began — aided by the immigration of Egyptians and Algerians, as well as the subsequent immigration of Algerians, Bosnians, and Circassians.

This is all to say that the Jews are evidently indigenous to the Levant (the Eastern Mediterranean region of West Asia, including Israel), not the Arabs; most of the latter arrived to this region from the Arabian peninsula, which today comprises Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

Still don’t fully believe me? This is corroborated by the Merneptah Stele, an inscription by an Egyptian pharaoh who reigned from 1213 to 1203 BCE. A majority of scholars translate a set of hieroglyphs in line 27 as Israel, within the context that Pharaoh Merneptah recounted his encounter with an Israeli kingdom during an ancient Egyptian military conquest.

This is even further corroborated by the Dead Sea Scrolls — the world’s oldest biblical manuscripts, considered to be a keystone in archaeological history — which were discovered in caves on the Dead Sea’s northern shore. They were initially moved to the Palestine Archaeological Museum, managed by Jordan.

But after Israel claimed Judea and Samaria (also known as the West Bank) following the Six-Day War in 1967, the Dead Sea Scrolls collection was moved to the “Shrine of the Book” at the Israel Museum, under the auspices of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The shrine houses the Isaiah scroll, dating from the second century BCE, the most intact of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Aleppo Codex, dating from the 10th century CE, the oldest existing Hebrew Bible.

The Israel Museum, an art and archaeological museum in Jerusalem, was established in 1965. Today, it is the country’s largest and foremost cultural institution, and one of the world’s leading encyclopaedic museums — with more than a half-million holdings, including the most comprehensive collection of Holy Land archaeology.

What you won’t find in the Levant is ancient archaeology specifically related to Palestinian history. While the timing and causes behind the emergence of a distinctively Palestinian national consciousness among the Arabs of Palestine are matters of scholarly disagreement, some argue that it can be traced as far back as the peasants’ revolt in Palestine in 1834 (or even as early as the 17th century).

This revolt was precipitated by heavy demands for conscripts. The local leaders and urban notables were unhappy about the loss of traditional privileges, while the peasants were well aware that conscription was little more than a death sentence. Starting in May 1834, the rebels took many cities — among them Jerusalem, Hebron, and Nablus — but they were defeated three months later in Hebron.

Others argue that Palestinian national consciousness did not emerge until after the Mandatory Palestine period (between 1920 and 1948). According to legal historian Assaf Likhovski, the prevailing view is that Palestinian identity originated in the early decades of the 20th century. At this time, an embryonic desire among Palestinians for self-government ensued, in the face of generalized fears that Zionism would lead to a Jewish state and thus the Arab majority’s dispossession.

The term “Palestinian” was first introduced in 1898 by Khalil Beidas in the Arabic translation of a Russian work on the Holy Land. After that, its usage gradually spread so that, by 1908, with the loosening of censorship controls under late Ottoman rule, a number of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish correspondents writing for newspapers began to use the term with great frequency in referring to the “Palestinian people,” “Palestinians,” the “sons of Palestine,” and “Palestinian society.”

While many presume that the Jewish return to our indigenous homeland started in or around the Holocaust circa 1939, our initial pioneers arrived in the mid-1800s. For example, legal Jewish settlements were developed near Jerusalem in 1850 by the American Consul Warder Cresson, a convert to Judaism.

Sir Moses Montefiore, famous for his intervention in favor of Jews around the world, established a colony for Jews in Ottoman-era Palestine. In 1854, his friend Judah Touro bequeathed money to fund Jewish residential settlement in Palestine. Montefiore was appointed executor of his will, and used the funds for a variety of projects, including building the first Jewish residential settlement and almshouse outside of the old walled city of Jerusalem in 1860.

In 1878, Petah Tikva was founded by Orthodox Jewish visionaries from Europe who purchased the land from two Christian businessmen. Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II allowed the purchase because of the land’s poor quality.2

A new era opened with the publication in 1879 of Eliezer Ben‑Yehuda’s article entitled “A Burning Question.” The use of Hebrew as a spoken language was to be for Ben‑Yehuda one of the most important aspects of the new plan for Jewish resettlement in the Land of Israel (then-Ottoman-era Palestine).

From 1881, Ben‑Yehuda lived in Jerusalem and, starting with his own family, forged ahead with his objective of changing Hebrew into a language suitable for daily use. One of his greatest endeavors was to develop an appropriate vocabulary, in which Ben‑Yehuda incorporated material from ancient and medieval literature and created new words eventually to be included in his monumental “Thesaurus.”

During this first stage of Hebrew’s revival as a spoken langauge, which lasted up to 1918, consideration was given to a number of problems in phonology (adaptation of Hebrew to the pronunciation of foreign names, resulting in the introduction of some graphemes that are followed by an apostrophe), orthography (adoption of a writing system), and morphology and syntax.

But the most pressing issue was the creation of new words, the basic task of Ben‑Yehuda and the Va’ad ha‑Lashon (Language Council), which began to operate in 1890. In the introduction to Ben‑Yehuda’s “Thesaurus,” the methods employed for adapting the language to everyday needs are explained.

In the following years, Jewish immigration to Ottoman-era Palestine started earnestly, including the official beginning of the construction of the “New Yishuv” (new Jewish communities), which is usually dated to the arrival of the Bilu group circa 1882.

Most immigrants came from the Russian Empire, escaping the frequent pogroms and state-led persecution in what are now Ukraine and Poland. They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe.

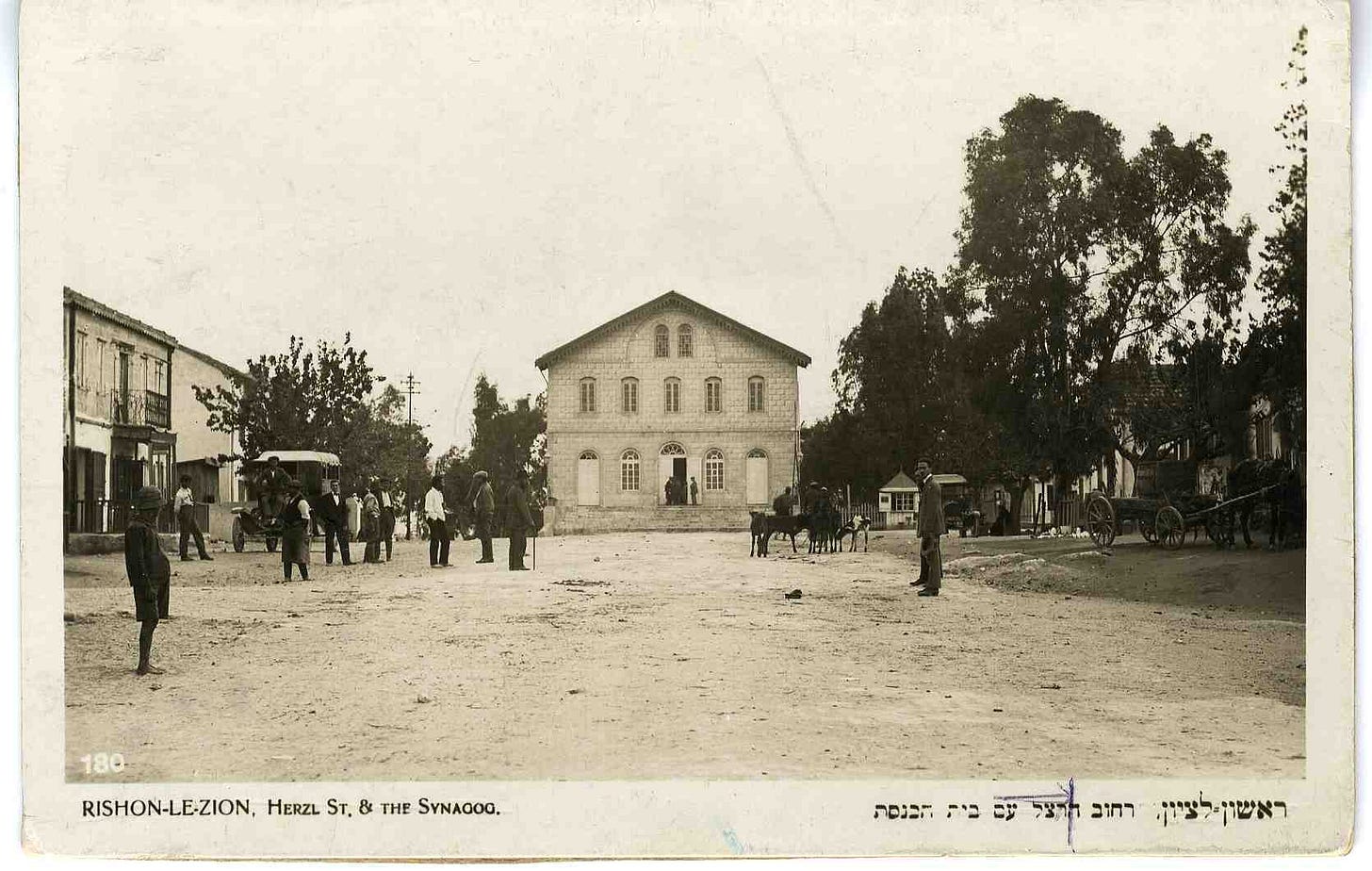

In 1885, the Great Synagogue of Rishon LeZion was founded, just a few kilometers south of present-day Tel Aviv. By the end of the nineteenth century, Jews were a growing minority in Palestine.

In the 1890s, Theodor Herzl infused Zionism with a new ideology and practical urgency, leading to the First Zionist Congress in Switzerland in 1897, which in turn led to the World Zionist Organization. From 1897 to 1901, the Zionist Congress met annually and thereafter biennially.

By the Sixth Zionist Congress, Herzl succeeded in arousing, establishing, and leading a dynamic and developing movement. Despite the fact that his goal of creating a Jewish state remained a distant reality, the growing epidemic of worldwide Jewish distress provided a firm basis for its success.

Neve Tzedek, now an upscale neighborhood in Tel Aviv, was founded in 1887 by Mizrahi Jews, due to overcrowding in nearby Jaffa.3 In 1909, some 66 Jewish families gathered on a desolate sand dune in what is now Tel Aviv, to parcel out the land by lottery, a whopping total of 0.05 square kilometers (12 acres).

Akiva Aryeh Weiss, president of the building society who organized the lottery, collected 120 seashells from the Mediterranean shore, half of them white and half of them gray. The families’ names were written on the white shells and the plot numbers on the gray shells. A boy drew names from one box of shells and a girl drew plot numbers from the second box.

According to legend, there was a man named Shlomo Feingold standing behind the group, on the slope of the sand dune, who opposed the idea, allegedly telling the others: “Are you mad? There’s no water here!”4

A photographer named Avraham Soskin happened to be roaming the area with a camera and tripod, on his way to Jaffa, walking through the sand dunes of what is today Tel Aviv.

“I saw a group of people who had assembled for a housing plot lottery,” Soskin recounted. “Although I was the only photographer in the area, the organizers hadn’t seen fit to invite me, and it was only by chance that this historic event was immortalized for the next generations.”

The first water well was later dug at this site, located on what is today Rothschild Boulevard, one of the city’s main streets. Within a year, a water system was installed and 66 houses were completed.

Originally called Ahuzat Bayit (literally “homestead” in Hebrew), the name Tel Aviv was adopted because the initial residents found it more suitable, since it embraced the notion of a renaissance in the ancient Jewish homeland. Aviv is Hebrew for “spring” (as in the season), symbolizing renewal. Tel is an artificial mound created over centuries through the accumulation of successive layers of civilization, built one over the other.

By 1914, Tel Aviv had grown to more than one square kilometer (247 acres), and a census recorded a population of 2,679 the following year. However, growth halted in 1917 when the Ottoman authorities expelled the residents of Jaffa and Tel Aviv as a wartime measure, aimed chiefly at the Jewish population. (Jews were free to return to their homes at the end of the following year when, with the First World War’s end and the defeat of the Ottomans, the British took control of Palestine.)

In 1917, lobbying by Chaim Weizmann, together with fear that U.S. Jews would encourage the United States to support Germany in the war against Russia, culminated in the British government’s Balfour Declaration. It endorsed the creation of a Jewish homeland in the Jews’ indigenous homeland, as follows:

“His Majesty’s government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

During the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, an Inter-Allied Commission was sent to British-era Palestine to assess the views of the local population; the report summarized the arguments received from petitioners for and against Zionism, prompting the League of Nations to adopt the Balfour Declaration and grant to Britain the Palestine Mandate. The commission said:

“The Mandate will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home ... and the development of self-governing institutions, and also safeguard the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.”

In that same year, the idea of a unique Palestinian state distinct from its Arab neighbors was rejected by Palestinian representatives, and the First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations adopted the following resolution:

“We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds.”

After the British general, Louis Bols, read out the Balfour Declaration in 1920, some 1,500 Palestinians demonstrated in the streets of Jerusalem. A month later, during the Nebi Musa riots, the protests against British rule and Jewish immigration became violent, and Bols banned all demonstrations. In 1921, however, further anti-Jewish riots broke out in Jaffa and dozens of Arabs and Jews were killed as a result.

After the Nebi Musa riots, the San Remo conference, and the failure of the King of Iraq to establish the Kingdom of Greater Syria, a distinctive form of Palestinian Arab nationalism took root. With the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the French conquest of Syria, coupled with the British conquest and administration of Palestine, the formerly pan-Syrianist mayor of Jerusalem, Musa Qasim Pasha al-Husayni, said:

“Now, after the recent events in Damascus, we have to effect a complete change in our plans here. Southern Syria no longer exists. We must defend Palestine.”

Violence between Jews and Arabs in the region erupted over the next three decades. Even then, the Jews stood ready to share the land with the Arabs as part of a two-state solution, starting with such a proposal in the 1936 Peel Commission, and again with the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.

While it’s true that Jewish organizations collaborated with the United Nations during the deliberations for this plan, the Palestinian Arab leadership boycotted it. Arab leaders and governments rejected the plan in the UN resolution and indicated that they would reject any other plan of partition.

The way I interpret this: The Jews worked their political magic, the Arabs stupidly decided not to be involved at all (bad optics in my opinion), and the Arabs refused to negotiate whatsoever with the Jews, even though the Jews are clearly indigenous to this land, going back thousands of years.

Ultimately, the Arabs decided they’d rather wage a war against the Jews and settle it militarily, a completely fair and even reasonable choice in my opinion. The Arabs not only lost this war in 1948, they also never came to terms with it, so they kept attacking Israel — and kept losing — in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s (even as Israel kept the option of a two-state solution on the table).

Ultimately, these wars and their unfruitful outcomes for the Arabs kept further hurting their proverbial ego and increasingly deranging them.

Eventually, Egypt and Jordan (which share borders with Israel) made peace with the Jewish state, realizing this was a better option than losing war after after against the Jews, but Syria and Lebanon remained hostile neighboring countries.

Meanwhile, since the 1960s, the Palestinians have continuously elected, opted into, or enabled governments which are inherently terrorist organizations designed to inflict as much harm as possible on Israel and Jews. Admittedly, I’m not sure how Israel can realistically achieve peace with a people who so easily indulge in terrorism against it.

Still, the Israelis have sincerely engaged in 10 different two-state solution proposals with the Palestinians since the 1930s, such as:

In 1936 (the aforementioned Peel Commission)

In 1947 (the aforementioned UN Partition Plan)

In 1949 (UN Resolution 194)

In 1967 (UN Resolution 242)

In 1978 (Begin/Sadat peace proposal)

In 2000 (Camp David peace proposal)

In 2001 (Taba peace proposal)

In 2008 (Olmert peace proposal)

In 2014 (Kerry’s “Conditions for Peace”)

In 2019 (Trump’s “Deal of the Century”)

In virtually all 10 cases, the Palestinian response has consistently been refusal to compromise in a way that would reasonably ensure Israel’s security, followed by grotesque violence and terrorism against Israelis (mostly Israeli citizens).

What’s more, Palestinians and their “partners” have supercharged extensive propaganda campaigns with claims that Israel is a colonizer, even going as far as to add the precursor “white colonizers.”

Not only is it so incredibly clear that Jews are indigenous to present-day Israel, but more than 60-percent of Israeli Jews have North African and Middle East descent, making them anything but “white.”

Another largely baseless claim from the encyclopedia of Palestinian propaganda is that some 700,000 Palestinians were expelled from modern-day Israel during the 1948 Israeli War of Independence.

In reality, many of these Palestinians were instructed by Arab leaders and Arab media to leave their homes, so five Arab countries could attack the Jews just a few hours after our declaration of independence. These Arab leaders and media assured the Palestinians that they could return to their homes after victory, but there was only one problem: They didn’t win.

Even Jordan’s King Abdullah, in his memoirs, blamed Palestinian leaders for the refugee problem, writing:

“The tragedy of Palestinian Arabs was most of their leaders had paralyzed them with false and unsubstantiated promises that they were not alone; that 80 million Arabs and 400 million Muslims would instantly and miraculously come to their rescue.”

“The Arab armies entered Palestine to protect the Palestinians from the Zionist tyranny,” Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Mahmud Abbas said, “but instead, they abandoned them, forced them to emigrate and to leave their homeland, and threw them into prisons similar to the ghettos in which the Jews used to live.”

Of the 150,000 Palestinians who didn’t flee their homes during Israel's War of Independence in 1948, they became Israeli citizens with equal rights, at least on paper. Today they represent more than 20-percent of Israel’s citizenry, its largest ethnic minority.

The Arab Israeli story is not all rainbows and roses, though, since they were subject to martial law in the early years of the Jewish state. According to Ian Lustick, an expert on the Middle East’s modern history, subsequent Israeli policies were “implemented by a rigorous regime of military rule that dominated what remained of the Arab population in territory ruled by Israel, enabling the state to expropriate most Arab-owned land, severely limit its access to investment capital and employment opportunity, and eliminate virtually all opportunities to use citizenship as a vehicle for gaining political influence.”5

Travel permits, curfews, administrative detentions, and expulsions were part of Arab Israelis life until 1966. A variety of Israeli legislative measures facilitated the transfer of land abandoned by Arabs to state ownership, including the Absentee Property Law of 1950, which allowed the state to expropriate the property of Palestinians who fled or were expelled to other countries; and the Land Acquisition Law of 1953, which authorized the Ministry of Finance to transfer expropriated land to the state.

Other common legal expedients included the use of emergency regulations to declare land belonging to Arab citizens a closed military zone, followed by the use of Ottoman legislation on abandoned land to take control of the land.

On the flip side, Arabs who held Israeli citizenship were entitled to vote for the Israeli Knesset (legislature) since the state’s founding, and Arab Knesset members have served in office since the First Knesset.

In 1966, martial law was lifted completely, and the government set about dismantling most of the discriminatory laws, while Arab Israeli citizens were granted the same rights as Jewish citizens under law.

According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics census in 2010, “the Arab population lives in 134 towns and villages. About 44-percent of them live in towns (compared to 81-percent of the Jewish population); 48-percent live in villages with local councils (compared to nine-percent of the Jewish population). Four-percent of the Arab citizens live in small villages with regional councils, while the rest live in unrecognized villages.”6

In the 1990s, Israel began implementing a unique race-neutral, class-based affirmative action policy at four top universities — Tel Aviv University, Hebrew University, the Technion, and Ben Gurion University. This policy does not look at students’ socioeconomics (which requires participants to volunteer private information). Instead, it targets students coming from poor neighborhoods and poor high schools, all information that’s on public record.7

In a 2004 survey from the University of Haifa Jewish-Arab Center, 85-percent of Israeli Arabs stated that Israel has a right to exist as an independent state, and 70-percent that it has a right to exist as a democratic, Jewish state.8

As with any country, there remains work to be done to perfect Israel’s democracy and ensure every citizen has equal opportunity access. People tend to compare Israel to other Western countries, but this comparison feels off.

The more relevant juxtaposition should be within the context of the Middle East, where Israel is the only democracy, as well as the sole country with a healthy combination of Jews, Muslims, and Christians.

Never mind that Israel, today, features one of the world’s strongest economies, while churning out the most college degrees per capita, the most museums per capita, the most startups per capita, the second-most scientific research per capita, the most hi-tech “unicorns” per capita, the highest-dairy-yielding cows, the world’s first egalitarian youth scouts movement and, since 1966, the most Nobel Prize winners per capita.

Plus, Hebrew’s revival as the State of Israel’s official language. This represents the world’s only example of a natural language without any native speakers subsequently acquiring several million native speakers, as well as the world’s only example of a sacred language becoming a national language with millions of native speakers.

When Israel was founded in 1948, just six-percent of the world’s Jews lived there. Today the country is home to approximately 40-percent of the world’s Jews, and Israeli Jews make up some 50-percent of worldwide Jewry, which is approaching its pre-Holocaust populace.

In just 75 years, the Jews managed to accomplish all of this in our indigenous homeland, while fighting existential war after war seemingly every decade. That’s why Israel is, in no short order, the greatest decolonization project on planet Earth.

“What is decolonization, why is it important, and how can we practice it?” Community-Based Global Learning Collaborative.

Yaari, Avraham (1958). “The Goodly Heritage: Memoirs Describing the Life of the Jewish Community of Eretz Yisrael From the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Centuries.”

“Tel Aviv.” Wikipedia.

“Old New Land: The Story Behind the First Photograph of the Founding of Tel Aviv, 1909.” Vintage Everyday.

“Zionist Theories of Peace in the Pre-State Era: Legacies of Dissimulation and Israel’s Arab Minority,” in Nadim N. Rouhana, Sahar S. Huneidi (eds.), Israel and its Palestinian Citizens: Ethnic Privileges in the Jewish State, Cambridge University Press, 2017 ISBN 978-1-107-04483-8 pp. 39–72, p.68.

“Housing Transformation within Urbanized Communities: The Arab Palestinians in Israel.” Geography Research Forum.

“Q&A: Israel and the Affirmative Action Debate.” Moment.

Professor (Emeritus) Shimon Shamir. “The Arabs in Israel – Two Years after The Or Commission Report” (PDF). The Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation. p. 7.

Brilliant writing and enlightening historical accuracy as always, Joshua Hoffman. I only wish the world still paid attention to truth.

Excellent article! Looks as though all the historical facts are in order. Seems like history is being re-written to fit a certain agenda.