The Subtle Art of Fighting Antisemitism on College Campuses

The overall response to fighting antisemitism on college campuses (and in other public arenas) has been one big failure. Here are some better ideas.

Editor’s Note: In light of the situation in Israel — where we are based — we are making Future of Jewish FREE for the coming days. If you wish to support our critical mission to responsibly defend the Jewish People and Israel during this unprecedented time in our history, you can do so via the following options:

You can also listen to this essay if you prefer:

About a week ago, the White House said it would send dozens of cybersecurity experts to help schools examine antisemitic threats. The U.S. Departments of Justice and Homeland Security are also reportedly working with campus police departments to track hate-related rhetoric.

As if the U.S. government has ever been adept at fighting prejudice and bigotry, but okay, more power to you.

Some of the nation’s most powerful law firms are warning America’s elite universities to crack down on antisemitism on campus — or the schools and their students “will face real consequences.”

Pungent language, sure, but we all know those law firms will do what’s in their best business interests when push comes to shove.

Within days after its launch on October 26th, the “Mothers Against College Antisemitism” Facebook group was exploding with posts from across the world, expressing alarm about what was happening at colleges and universities following the Palestinian terrorists’ massacre in Israel on October 7th.

Everyone loves a good Jewish mother, but I’m not sure we need another social media group to let us know that roses are red and violets are blue.

Hillel International, the Anti-Defamation League, the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, and and the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher recently announced the Campus Antisemitism Legal Line (CALL), a free legal protection helpline for students who have experienced antisemitism.

I appreciate the effort, but let’s be honest: Do Jews really need a free legal protection helpline? And how did Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher finagle their way into becoming the de facto litigators against antisemitism on college campuses? Well played.

Speaking of the Anti-Defamation League, their “best practices” for preparing one’s self against antisemitism and anti-Israel bias on campus includes cliches like:

Counter hate speech “with more positive engagement and education.”

Establish “an environment for a mutually respectful.”

Strive “for a common language.”

“Conclude the discussion with next steps for learning and supportive actions.”

The organization also encourages people to “report” incidents “to your Hillel” — referring to the multi-campus organization that has existed for literally 100 years. If Hillel had the competence to effectively fight antisemitism and anti-Israel on college campuses, it would have already done so.

Instead, the organization’s vice president of University Initiatives and Legal Affairs suggests Jews adopt “the three A’s” to combat antisemitism: awareness, allyship, and action. At best, “the three A’s” is a cute catchphrase; at worst, it sounds like something meant more for kindergartners than college students.

Another prescription from the Anti-Defamation League: “Work with campus officials and partners to provide educational workshops.” Seriously now, do you actually expect college students to seek out for another “educational opportunity” during their time on campus?

In a recent article on the website Philanthropy Roundtable, one writer outlined “how donors can fight rising antisemitism on college campuses” — as if the idea of “donors fighting antisemitism” was born yesterday. Haven’t we already thrown a gross amount of money at these problems?

Yes, I know, everyone in the fight against antisemitism and anti-Israel has been acting with the best of intentions, but let’s stop being so soft. And let’s start confronting the unfortunate truth: The overall response to fighting antisemitism and anti-Israel on college campuses (and in other public arenas) has been counterproductively high-brow, a predominant waste of money, uninspiring, lacking creativity, and at times naive and ignorant.

To add insult to injury, you could easily make the argument that the overall response to fighting antisemitism and anti-Israel on college campuses (and in other public arenas) has actually made these trends worse.

But I’m not just here to doll out jabs and insults, so I’ve pondered some “more outside the box” approaches that Jews across the world can use to diminish antisemitism and anti-Israel in every public venue. Here we go:

1. You fight by fighting back.

I want to preface this section by saying that, in general, I’m anti-violence. If there’s a genuine opportunity to engage civilly and diplomatically, I’m all for it.

But most antisemites are not so keen on civility and diplomacy, preferring to spew dangerous propaganda and other ridiculous rhetoric as their voices grow obnoxiously louder.

The one thing about these antisemites, though, is that many of them shy away from direct physical aggression against Jews. Even among those who appear to threaten physical aggression, many are just posing as “tough stuff.”

Usually, physical aggression tends to be escalatory, but in the case of antisemitism and anti-Israel, physical aggression (as a means of self-defense) has a good chance of being deescalatory, since many antisemites don’t expect it from Jews — and will fold their cards accordingly.

In addition, standing up to antisemitism and anti-Israel with physical aggression (again, in self-defense) will put others who think about displaying their Jew hate on notice: Wanna wave your antisemitic flags? You’ll face these consequences as well.

To effectively fight back with physical aggression, Jews will be tasked with learning how to fight. Krav Maga seems like a nice place to start, although any form of combat will suffice.

It’s also important to note that today’s Jews wouldn’t be the first to fight back. In some 100 ghettos across Eastern Europe during Nazi Germany’s reign, underground organizations were formed to wage armed struggle. In several concentration camps, Jewish forced-labor workers initiated uprisings. And following the Holocaust, some Jews even hunted Nazis who were still alive.

The point is, if we don’t stand up for ourselves, or if we “back down” and, even worse, demonstrate fear in the faces of antisemites (which is often the case on college campuses), we’re emboldening antisemites to do what they obnoxiously do, and more of it.

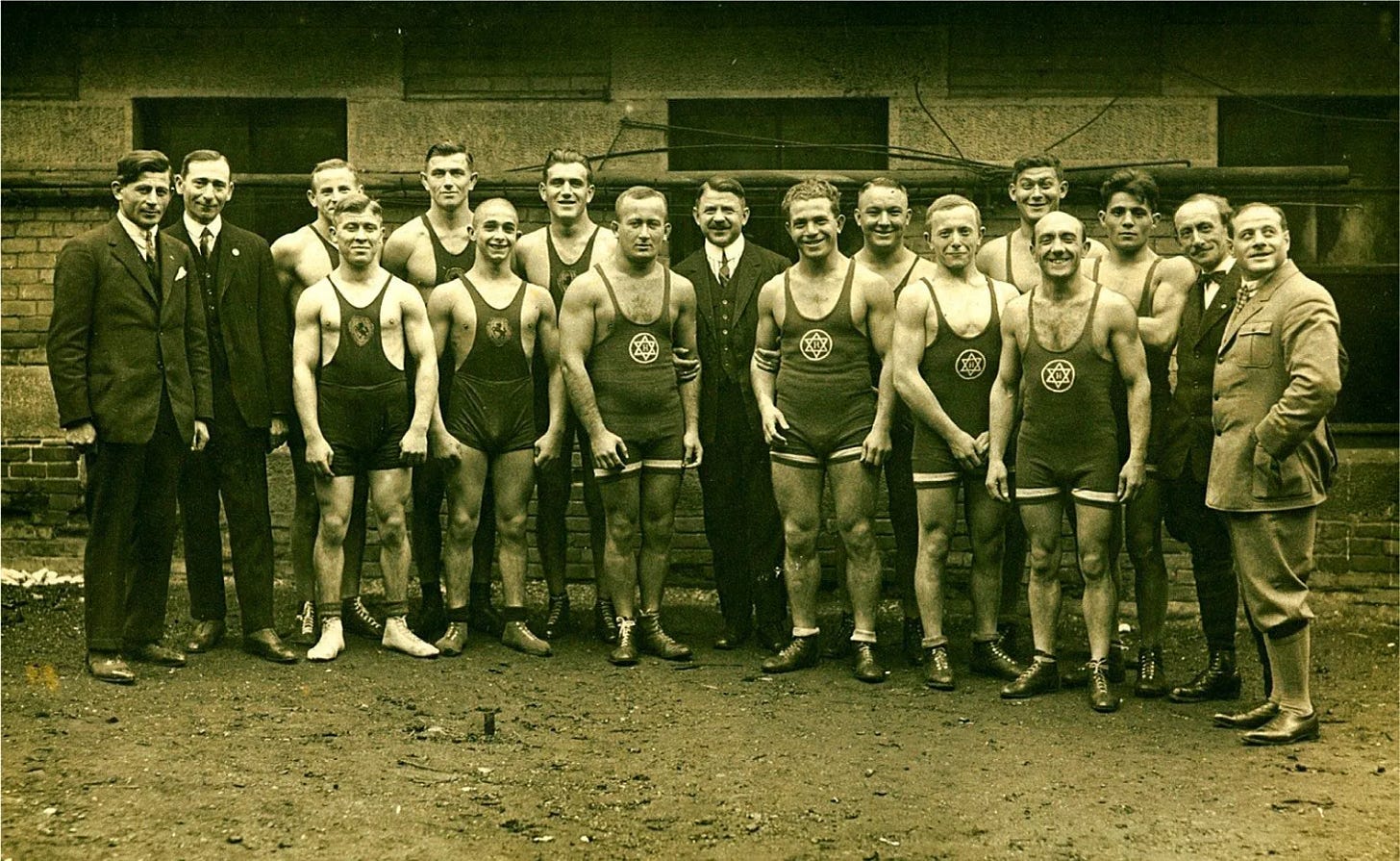

2. Muscular Judaism

Max Nordau, a Zionist leader and physician who was born in 1849 in Hungary, perceived the characteristics of 19th-century European Jews to be problematic in dealing with antisemitism (which at the time was a million times worse than its present-day forms).

According to Nordau, 19th-century European Jews were often the rabbinic or Haskalah Jews — the Jews of letters, intellectuals — who were said to be busy all their life engaging with esoteric subjects. Nordau believed their bodies grew weak, which is why he saw the promotion of athletic Jews (what he called “Muscular Judaism”) to be a profound prescription against antisemitism.

“Muscular Judaism” refers to the cultivation of mental and physical properties, such as strength, agility, and discipline, which Nordau believed were all necessary for the Jewish People’s national revival.

Advocating for a transformation to “deep-chested, sturdy, sharp-eyed” Jews that would vanquish negative perceptions of them, Nordau argued that mental and physical strength would be an imposing response to “Jewish distress” in antisemitism-infested Europe.

Over time, Jews who went on to adopt “Muscular Judaism” experienced an increase in self-confidence, a critical ingredient in the Jewish fight against antisemitism.

3. Jewish Bodyguards

In 1909, two Austrian Zionists and prominent Jewish businessmen founded the first Jewish sports club and named it Hakoach (הכח), meaning “the strength” or “the power” in Hebrew.

At the time, Jews in Vienna numbered 180,000 — about 10-percent of the city’s population — and many of them were intoxicated with the aforementioned doctrine of “Muscular Judaism.”

David Herbst, the sports club’s president from 1928 to 1938, echoed this sentiment, saying:

“In the days of our forefathers, we Jews have completely forgotten the old and true words in the education of our children: Mens sana in corpore sano! We only thought that the new generation should be educated. We neglected what today the whole world recognizes as the only proper educational principle: to make our bodies strong.”

During its first year, the Jewish sports club’s members competed in fencing, field hockey, track and field, wrestling, swimming, and football — eventually expanding its roster to other athletics and attracting Jewish athletes from across Europe.

Their football team was one of the first to market itself globally through frequent travel, attracting thousands of Jewish fans in London and New York, as well as in South America, Africa, and other cities throughout the United States. They also garnered the attention of prominent Jewish figures, such as the author Franz Kafka.

After touring Germany in the early 1920s, a prominent newspaper commented that the club “had helped to do away with the fairy tale about the physical inferiority of Jews.”

However, the football team regularly faced antisemitism during its travels, so they created an unconventional form of security: The sports club’s wrestlers accompanied them, acting as their personal bodyguards.

What if, when Jews demonstrate on college campuses and in other public venues, they are joined by Jewish bodyguards — Jews who are physically fit and poised to fend off rowdy antisemites?

4. The ‘New Jew’ Mentality

Many young Jews seem to lack resilience nowadays, a trend heightened by environments which over-emphasize “safe spaces” — only making them less resilient, or what I’ll call “fragile Jews.”

The fragile Jew reminds me of, albeit under different circumstances, many Jews before the State of Israel, who displayed an older Jewish pattern of relying on powerful non-Jewish guardians, whose ongoing protection had to be secured through techniques such as politics and business.

But the State of Israel, founded in 1948, transformed an extraordinary amount of Jews. It made these Jews more confident, more ferocious, more daring, more adventurous, more optimistic, more heroic, more glorious.

And it led to a conception of the “New Jew” whose “soul and character would be purged of the disfigurements impressed upon the Diaspora Jew by millennia of exile,” according to Eli Spitzer, headmaster of a Hasidic boys’ school in London.

“Each Zionist thinker differed in identifying which aspects of the Old Jew were particularly objectionable, and thus which aspects of the New Jew were most crucial to inculcate,” Spitzer added, “but all agreed that something had gone drastically wrong in Jewish history which went far beyond the persecution that Jews had suffered at Gentile hands.”

Here’s an interesting way to understand the difference between Old Jews and New Jews:

The State of Israel makes a formal announcement, warning that it’s dangerous for Jews to travel to Turkey for the foreseeable future. The Old Jew heeds Israel’s warning and stays far away from Turkey, while the New Jew (typically the Israeli Jew) responds with something like, “C’mon now, there’s no reason to be afraid. I was in the army. My cousin is in the Mossad. Everything will be okay. When is the next flight to Istanbul?”

All humor aside, the Old Jew is still very much present, especially in places like the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, and South Africa. And many Old Jews run thousands of Jewish organizations, financed with billions of dollars by Old Jew philanthropists. In other words, these organizations, which are meant to serve all Jews and Jewish communities, only propagate more Old Jew attitudes and paradigms like victimhood, anxiety, and fear.

The result? Many of today’s young Jews are more insecure, more easily offended, and more reliant on others. They have been taught to seek authority figures to solve their problems and shield them from discomfort, a condition sociologists call “moral dependency.”

To be sure, our elders have had the best of intentions, but efforts to protect younger Jews are backfiring. When we raise Jewish kids unaccustomed to facing anything on their own — including antisemitism — the Jewish People are threatened.

Perhaps an Old Jew can never fully become a New Jew — and I’m not sure they need to. I actually believe that the “muscular” Jew and the so-called rabbinic Jew are not mutually exclusive. Nowadays, I think they make for a complete Jew: one who is both intellectually driven and physically and mentally fit.

5. Israel as the Epicenter

Naturally, it’s easy for Jews to be proud, forthright, brash, optimistic, and confident when you live in a Jewish country, amongst a Jewish majority. But that’s exactly the point: The State of Israel is the most effective way to abate antisemitism.

Quite literally, the Mossad has departments whose job is to look after Jews across the world, even if these Jews don’t live in Israel, and even if they aren’t Israeli citizens. What does the Mossad do exactly? It works with other intelligence agencies to monitor and thwart antisemitic attacks across the world, which you almost never hear about because the very nature of intelligence is to operate covertly.

Yet more and more Jews across the world are becoming increasingly picky and choosy about their relationship with Israel (or lack thereof). To me, a Jew who doesn’t support the State of Israel (i.e. the Jewish homeland) is just as dangerous as a person who’s antisemitic. (Notice how I wrote “the State of Israel” and not “the government of Israel” or “the politicians of Israel.”)

Diaspora Jews ought to be continuously improving and enhancing their relationship with Israel, and Israel ought to be doing the same with them. It’s a two-way street, and the more that Diaspora Jews engage with Israel, the more Israel (both the State and everyday Israelis) will engage with them.

I get it, though, visiting Israel on a regular basis isn’t always convenient and affordable. Still, there are several other ways to engage with Israel on a day-to-day basis, such as a watching Israeli movies and TV shows; following Israeli social media accounts, thought leaders, and influencers; learning modern-day Hebrew; eating at Israeli restaurants in major cities across the world; and volunteering with organizations which deploy Israelis across the world, such as the Jewish Agency for Israel.

The point is, the Diaspora-Israel relationship is essential, because the stronger and more unified that Israeli and Diaspora Jews are, the more antisemitism becomes powerless, and the more the Jewish People of today and of future generations will thrive.

My American born dad was 'musclejuden' and raised me to be the same. If I am not for myself who will be for me?

Sent it to my much loved Rabbi Amy Bernstein. We have a pre school. She studied with Hartman for several years. We are Reconstruction Jewish. I will send to Facebook group.