The world keeps trying to rebuild Gaza — and failing.

From British blueprints to billionaire fantasies, every grand vision for Gaza has collapsed under the weight of war, terror, and history.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay by Oren Kessler, author of, “Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict.”

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

Heads spun a few months ago when U.S. President Donald Trump unveiled a plan to depopulate, raze, and rebuild the war-battered Gaza Strip.

He followed with an AI-generated video showing him drinking and dining beachside with Elon Musk and a shirtless Benjamin Netanyahu, as dollars rained on Gazan children. (The clip’s Israeli creators later said they made it as a “satire” and had no idea how it reached the White House).

But brazen as it is, the U.S. president’s plan is not the first time a superpower has floated an extreme postwar makeover of the ancient city.

Gaza’s location as the southernmost city on the Eastern Mediterranean has made it a gateway to the Holy Land for invaders from the pharaohs to Napoleon. So too for the British: In 1917 it was the scene of three battles — the First, Second, and Third Battles of Gaza — that saw some of the heaviest fighting in the Great War’s Middle Eastern theater.

General Edmund Allenby finally entered the city on November 9th, the day the British press published UK Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour’s declaration a week earlier endorsing a Jewish homeland in British Mandatory Palestine. The city he found was an abandoned ruin. Hundreds of buildings had collapsed; its population had mostly fled.

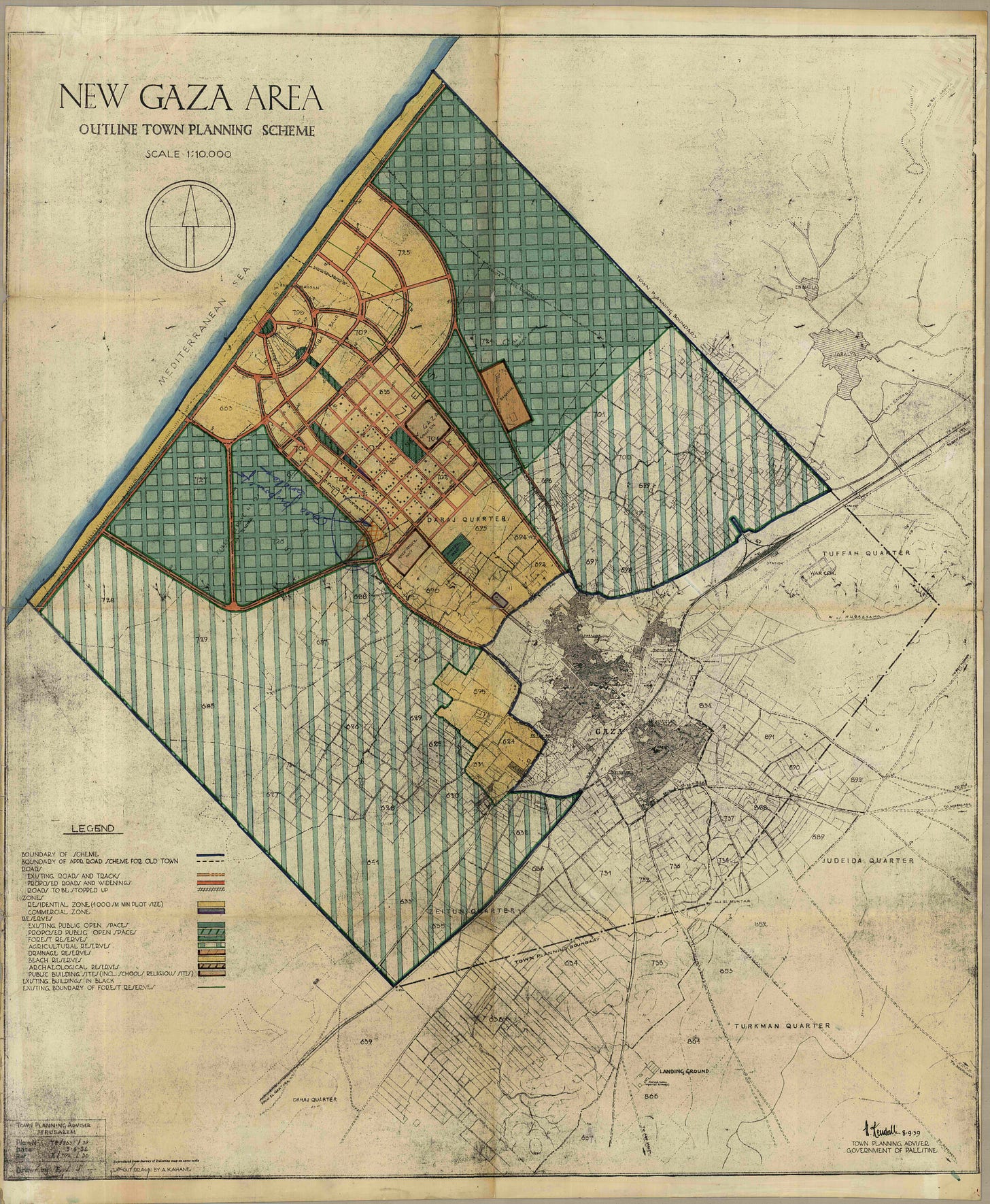

In the years that followed, Palestine’s new British Mandate authorities drafted a plan to rebuild, expand, and modernize the city. The project was intended to reclaim the sand dunes between Gaza and the sea that threatened to subsume what remained of the city and the surrounding farmland that sustained it.

More ambitiously, it aimed to turn Gaza into a modern resort and commercial hub with new planned neighborhoods, shopping zones, open spaces, a modern beach, advanced infrastructure, and forest reserves.

In 1936, Palestine’s senior urban planner, Henry Kendall, published the plan. He called it “New Gaza.”

But the Great Arab Revolt that erupted in April stalled the project, and the start of the Second World War in 1939 put it to bed. Only one portion of New Gaza was ever built: a neighborhood atop the coastal dunes that locals called “the Sands.”

Gaza’s roots run deep, even by the Holy Land’s formidable standards. Established by Canaanites at least four millennia ago, it was settled in the 12th century BC by Philistines, a mysterious Sea People believed to originate in Crete.

In the Book of Judges, Gaza is where Samson, hero of Israel, is imprisoned and meets his death: “Then the Philistines seized him, gouged out his eyes, and took him down to Gaza.”

The Judean prophet Amos prophesied its destruction: “I will send fire on the walls of Gaza; that will consume her fortresses.” So too Zephaniah: “Gaza will be abandoned and Ashkelon left in ruins. At midday Ashdod will be emptied and Ekron uprooted.”

Over the centuries, a succession of dynasties came and went: Egyptians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Maccabees, and Romans. The Arabs arrived in the 7th century CE, followed in later eras by Crusaders, Fatimids, Mamluks and, for exactly four centuries (1517 to 1917), the Ottomans.

In the early 1920s, British Mandate Palestine’s first high commissioner — Lord Herbert Samuel, a Jew and a Zionist — revived a decades-old Ottoman plan for the city’s modernization. The Gaza Development Scheme granted the municipality 5,000 dunams (1,200 acres) of dunes between the old city core and the sea to divvy up as lots for a new luxury suburb.

“The opening of the zone next to the beach for building enabled the construction of the smart modern suburb of Rimal (The Sands),” wrote French professor of Middle East studies Jean-Pierre Filiu1, one of the only comprehensive chronicles of the city.

A forestry expert named Gilbert Sale was summoned from Mauritius. His diligent staff experimented with various trees and shrubs to halt the dunes. The biblical Tamarisk, or salt cedar, proved particularly effective.

“Extensions of the town of Gaza are being contemplated,” one Mandate bureaucrat wrote in Empire Forestry Journal. “Dunes, being close to the sea, are attractive places to dwell in, and we already have an example in the township of Tel Aviv, of 23,000 inhabitants, erected on a sand dune.”

British officials soon moved into Rimal’s new European-style detached homes and villas. So did Arab merchants and landowners, shifting the economic center of gravity there from the old city center. An Ottoman-era street, Omar al-Mukhtar, was transformed into a leafy main boulevard that would not have been out of place on the continent.

Kendall’s 1936 plan showed a few dozen dots — representing those houses already built — that he hoped to link to a large “public open space,” forest and agricultural reserves, and neat roads leading residents to the sea in one direction and “Old Gaza” in the other.

But then came the Arab revolt.

“The reclamation of sand dunes was continued on a small scale at Gaza,” the government noted gloomily, “but all experiments were hampered by the disturbances.”2

Members of the royal commission sent to investigate the rebellion’s causes were likewise keen to learn about New Gaza’s progress. They asked Lewis Andrews, the senior Mandate official who served as their Arabic translator: “We understand that there is a scheme for buying some sand dunes near Gaza to develop a town or village there?”

“I think I am correct,” replied Andrews, “in saying that that project has fallen through.”

Less than a year later Andrews was shot dead by followers of a jihadist preacher named Izz al-Din al-Qassam, after which Hamas named its so-called “military wing.” It would not be the last time Gaza’s future would be mortgaged by acts of terrorism committed in Qassam’s name.

Before 1948, Gaza’s population of 30,000 made it British Mandate Palestine’s fifth-largest city (after Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, and Jaffa) and its largest purely Arab one.

The war which erupted that year saw the city of Gaza become the lynchpin of a Palestinian enclave — the Gaza Strip — that absorbed at least 200,000 refugees from southern parts of British Mandate Palestine now absorbed into the new State of Israel.

Amid Gaza’s transformation, Rimal retained its prestige. “Rimal is the lone elite district of the city,” according to one account.3 It is there that Gaza’s doctors, lawyers, businessmen, and their families are likeliest to make their homes.

In Rimal one finds Gaza Mall (a multimillion-dollar project opened in 2010); the Roots hotel and restaurant, popular with foreign press; the exclusive United Nations beach club (open only to UN workers and journalists); and the Gaza branch of the Palestinian Legislative Council, an abandoned relic of the more hopeful era of the Oslo Accords4. There too sits Shifa Hospital, originally a British army barracks, later modernized and expanded by architects from Tel Aviv.

It was only in 2014, after that year’s 50-day summer war, that Hamas leaders started gradually moving their homes and offices — and weapon stores — to Rimal. Over the next few years, reports began appearing in Israeli media that Hamas had taken control of the area.

In 2021, Rimal got its first, bitter taste of modern war, as Israeli jets struck the quarter during the eight-day Operation Guardian of the Walls. The largest airstrike, near Shifa Hospital, was the deadliest single act of the war, killing 44 people according to Hamas health officials.

But it is only in the current war that images began emerging from Rimal of the kind for which Gaza has become notorious.

“‘Incomprehensible Scenes’ — Gaza’s Upscale Neighborhood Turned into Ruins,” Hebrew media reported on October 10, 2023, just three days after the Hamas-led massacre in Israel.

“Unprecedented Israeli bombardment lays waste to upscale Rimal, the beating heart of Gaza City,” the AP reported, noting that although the army had ordered civilians to evacuate, many had stayed put out of uncertainty or the absence of anywhere safer to go.

Key sections of Omar al-Mukhtar street, the centerpiece of “New Gaza,” are erased.

“Ruin, ruin everywhere,” one Rimal resident posted to Arabic social media. “Not one stone remains upon another.”

Jews have lived in Gaza City at various times since the Roman era. The sixth-century Gaza Synagogue featured an elaborate mosaic (later moved to the Israel Museum) of King David playing the lyre. (Early in the present war, IDF troops were seen praying at the site, before a nearby building was designated as a synagogue.)

In the 17th century, the mystic Nathan of Gaza was the leading promoter of the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, even after the latter’s forced conversion to Islam. And in the early 20th century, Zionist groups considered purchasing the dunes on which Rimal would later rise.

“We were interested in [Ottoman] government lands about 3 to 4 kilometers long between Gaza and the sea. There we thought of establishing a Jewish neighborhood, a sort of Ahuzat Bayit,” wrote the head of the Israel Land Development Company, referring to the original name of Tel Aviv.

But Gaza’s small Jewish community ceased to exist after the 1929 Hebron massacre in which 60-plus Jews were murdered, so British authorities evacuated Gaza’s Jewish community for their safety.

After the 1967 Six-Day War, when Israel took control of Gaza from Egypt, some dreamed of recreating a Jewish presence there. A raucous debate erupted in Israel over the wisdom of such a move, but ultimately 21 settlements were created in the narrow Strip — including Netzarim, just south of Rimal.

In 1972, opponents of Gaza settlement from 13 farming communities along the Gaza border met at a small kibbutz just half a mile from the frontier: Nir Oz.

“War is too serious a matter to be left to the generals alone, and peace is even more complicated,” the conference organizer wrote in an op-ed. “Is the government promoting a wise and thought-out plan to solve the problem of the Strip? We believe it is not.”5

“How many people in Gaza can be evacuated for ‘security reasons?’” he wrote. “We must honestly answer a simple question: What will be the fate of the Gaza Strip?”

The writer was Oded Lifschitz. Born during British Mandate Palestine, he helped found Nir Oz as a teenager and lived there ever since. Lifschitz was kidnapped on October 7th from his home to Gaza; his body was returned in February as part of an Israel-Hamas ceasefire agreement. He was 83.

“Gaza: A History (Comparative Politics and International Studies) 1st Edition.” Oxford University Press. 2014.

“Report by His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain.”

Doughty, Dick. “Gaza : legacy of occupation--a photographer's journey.”

A series of agreements signed between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization in the 1990s, aiming to establish a framework for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

“כבר ב-1972 עודד ליפשיץ חזה את התהליכים שאנחנו עדים להם היום.” Haaretz.

Incredible research and history—thank you for article.

So what is the conclusion? My takeaway is that Israel has to annex Gaza, declare Jewish sovereignty, flood it with Jews and put the Muslim Arabs there under lockdown for fifty years while the latter slowly leave or learn to accommodate themselves to having limited municipal responsibilities with no voting rights in Israel. But that requires Jews understanding that there are no innocent civilians in Gaza. And the way to do this is to demand the immediate return of all hostages, failing which Gaza and its population will be immediately destroyed even more than it has been. Such is the price of conducting a hundred year war.