This is not a good way to fight antisemitism.

Imagine if the Black Lives Matter movement had framed its messaging around “All Lives Matter.” Such an approach would have been seen — rightly — as dismissive and counterproductive.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

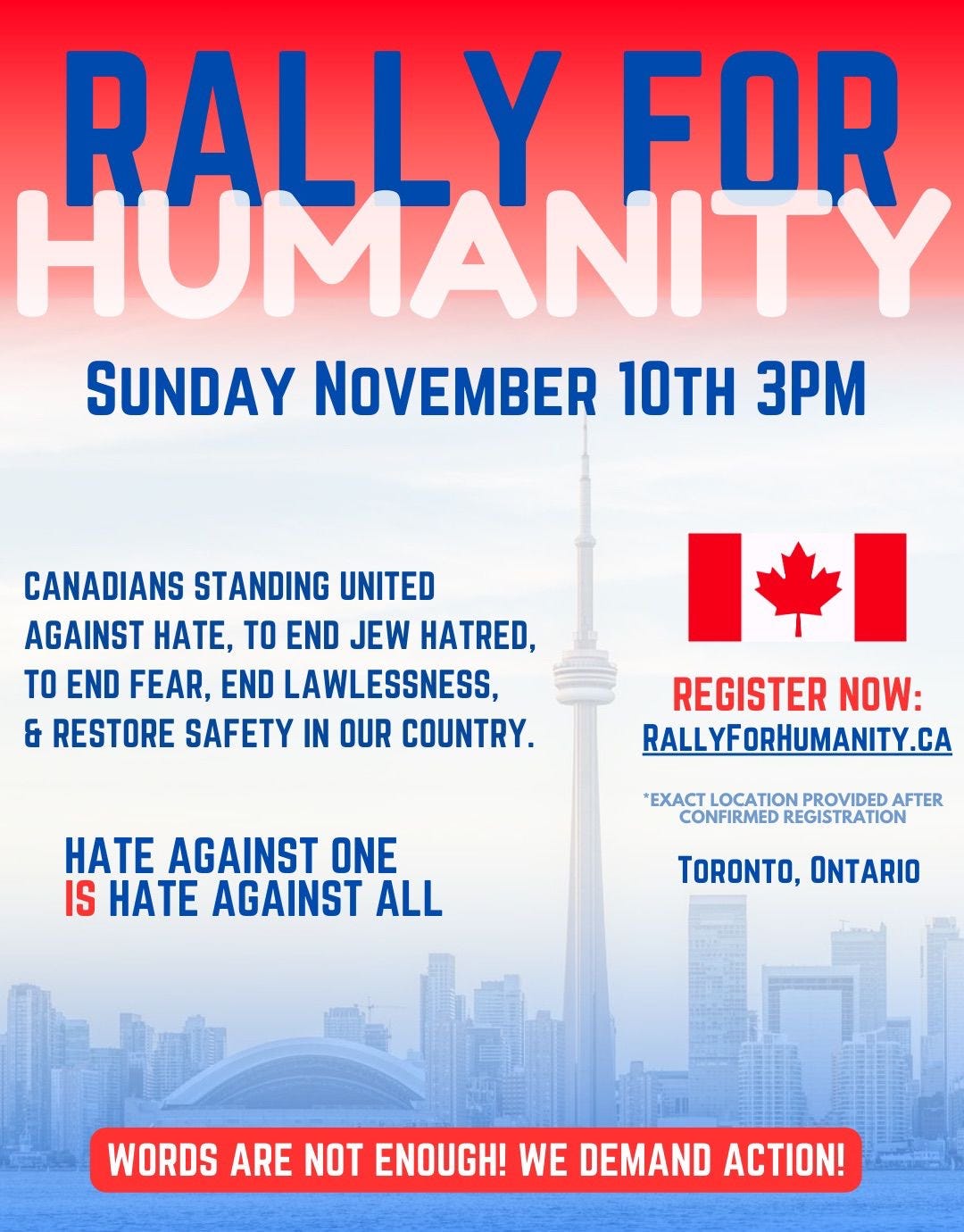

It was a brisk autumn day in Toronto when thousands gathered for what was billed as a “Rally for Humanity.”

The event promised to unite people against all forms of hatred and discrimination. Signs proclaiming “Stop Hate,” “Love is Love,” and “Humanity First” dotted the crowd. Among the throng were Jews holding placards referencing October 7th and denouncing hate in all its forms.

The event was well-intentioned, heartfelt, and inspiring — but it also illuminated a persistent and deeply ingrained issue within Jewish communities. Jews, as they have often done throughout history, grouped themselves into the broader “us” of humanity, failing to specifically and unapologetically call out Jew-hatred for what it is.

This phenomenon, where Jews align their struggles with universal messages rather than explicitly addressing antisemitism, is not new. From civil rights movements to broader campaigns against hatred, Jewish communities have long been leaders and participants in universalist causes.

But in doing so, we often fail to assert our unique vulnerability as a people. This “us” problem — where Jews align with the rest of society without differentiating our particular struggles — has profound consequences. It not only dilutes the conversation about antisemitism but also perpetuates the erasure of Jew-hatred as a unique and persistent form of bigotry.

The "Rally for Humanity": A Case Study

The “Rally for Humanity” was, on the surface, a noble endeavor. Its aim was to bring together people from all walks of life to denounce racism, xenophobia, and antisemitism.

Yet, among the speeches and slogans, something critical was missing: specificity. While speakers referenced October 7th and the importance of standing against all forms of hate, there was little mention of the specific and escalating threats faced by Jews today. This omission was not accidental; it was strategic. Organizers and participants feared that focusing too heavily on antisemitism might detract from the event's universal appeal.

Many Jews in attendance seemed content with this approach. They carried signs that read, “Never Again for Anyone” and “Hate is Hate.” These slogans, while well-meaning, encapsulate the problem. They suggest that Jew-hatred is just another flavor of the broader bigotry buffet.

But antisemitism is not merely “hate.” It is a unique and ancient form of scapegoating that morphs across centuries and societies, often targeting Jews regardless of their actions or affiliations.

The ‘Stand Up to Hate’ Campaign: Universalism at Its Best and Worst

In the United States, the “Stand Up to Hate” campaign has taken a similar approach. Spearheaded by billionaire NFL owner Robert Kraft’s organization “Foundation to Combat Antisemitism,” the campaign aims to combat hate crimes and promote unity.

As with the “Rally for Humanity,” the campaign’s messaging is broad and inclusive to a fault. It lumps antisemitic graffiti, harassment, and physical assaults together with instances of other bigotries. The universal framing — while admirable in its intent to foster solidarity — once again failed to address the specific and alarming rise in Jew-hatred.

Why does this matter?

Because antisemitism is often invisible in these universal narratives.

When a synagogue is vandalized or a Jewish student is harassed on campus, these incidents are subsumed under the generic banner of “hate.” The unique historical, cultural, and social dimensions of antisemitism are ignored, making it easier for society to overlook or dismiss these acts as isolated incidents rather than part of a broader pattern.

The Roots of the ‘Us’ Problem

To understand why Jews often fall into the trap of universalism, we must consider both historical and psychological factors.

Historically, Jews have survived by blending in. In the Diaspora, aligning with broader societal movements often provided a measure of safety and acceptance. This survival mechanism became deeply ingrained over centuries of persecution.

Psychologically, many Jews feel uncomfortable asserting their particularity. In a world that prizes inclusion and diversity, calling attention to antisemitism can feel parochial or even selfish. Some fear that emphasizing Jew-hatred might alienate allies or make Jews appear overly concerned with their own plight. This fear is not unfounded; history is littered with examples of Jewish advocacy being met with suspicion or hostility.

But this reluctance to assert our particularity comes at a cost. By failing to name and confront antisemitism explicitly, we allow it to fester and evolve unchecked. Worse, we send a message — both to ourselves and to the world — that Jew-hatred is not a pressing issue. This erasure not only undermines efforts to combat antisemitism but also leaves Jews increasingly vulnerable.

Why Specificity Matters

The danger of universalism is that it dilutes the unique experiences and struggles of marginalized groups.

Imagine if the Black Lives Matter movement had framed its messaging around “All Lives Matter.” Such an approach would have been seen — rightly — as dismissive and counterproductive. Specificity matters because it forces society to confront uncomfortable truths. It compels us to acknowledge that some forms of hatred require targeted responses.

Antisemitism is not just another form of bigotry; it is a unique phenomenon with its own logic and manifestations. Unlike other forms of hate, which often target visible differences, antisemitism frequently paints Jews as powerful, conspiratorial, and malevolent. This “punching up” dynamic makes it harder to recognize and address, especially in progressive spaces where Jews are often perceived as privileged.

By failing to assert the specificity of antisemitism, Jews contribute to this erasure. When we chant “Hate is Hate” or “Never Again for Anyone,” we obscure the unique threats we face. This is not to say that Jews should abandon universal causes or solidarity with other marginalized groups.

But we must do so without sacrificing our particularity. We can and should say: “Yes, all hate is wrong, but antisemitism is a specific and escalating threat that requires focused attention.”

The Cost of Erasure

The consequences of failing to name antisemitism are far-reaching.

When Jews align their struggles with universal messages, they inadvertently make it easier for society to ignore their plight. This erasure has real-world implications. It affects how antisemitic incidents are reported, investigated, and prosecuted. It influences public perception, making Jew-hatred seem less urgent or pervasive than it actually is.

Perhaps most importantly, this erasure affects Jewish communities themselves. When we fail to name and confront antisemitism, we internalize the message that our struggles are not worth prioritizing. This erodes communal confidence and resilience, making it harder to mobilize against threats.

It also sends a dangerous signal to younger generations of Jews, who may come to believe that their safety and identity are secondary to broader societal goals.

Reclaiming the Narrative

To address the “us” problem, Jews must reclaim the narrative around antisemitism.

This starts with language. We must be unapologetic in naming Jew-hatred for what it is, without hiding behind euphemisms or universal slogans. When antisemitic incidents occur, we must call them out explicitly and demand targeted responses.

This also means rethinking our approach to solidarity. True solidarity does not require erasing our particularity. On the contrary, it demands that we assert it.

By standing unapologetically as Jews — and by naming antisemitism as a specific and urgent issue — we set an example for other marginalized groups. We show that it is possible to fight for universal justice while also addressing particular injustices.

The “Rally for Humanity” and the “Stand Up to Hate” campaign are noble efforts, but their universal framing illustrates the dangers of being too broad. By failing to name antisemitism explicitly, these initiatives — however well-meaning — contribute to the erasure of Jew-hatred as a unique and pressing issue. This erasure not only undermines efforts to combat antisemitism but also leaves Jewish communities increasingly vulnerable.

Jews have an “us” problem. We are too quick to align our struggles with broader societal narratives, often at the expense of our particularity. This universalism, while well-intentioned, is counterproductive. It dilutes the conversation about antisemitism, making it easier for society to ignore or dismiss our unique challenges.

If we are to combat antisemitism effectively, we must be unapologetic in naming it for what it is. We must assert our particularity without fear or hesitation. Only by doing so can we ensure that Jew-hatred is recognized, confronted, and ultimately eradicated.

Specificity is not selfish; it is necessary. And until we embrace it, we will continue to face the dangerous consequences of being too broad in our advocacy.

Very interesting. I also noticed that whenever politicians particularly in the United Kingdom and Australia condemn antisemitism, they always attach it with being against “Islamophobia”. That tends to dilute the problem of antisemitism that we have today.

One of my major gripes is when people have to include other hatreds when condemning antisemitism. Nobody does that for any other form of bigotry. Remember when Congress had to "all lives matter" antisemitism when Pelosi was Speaker. Somehow you can't just be against Judenhass. That Jews buy into this is ridiculous. The diaspora Jewish communities are led by useless and spineless people.