This is what Jew-haters won’t tell you.

Medieval usury laws have a long-reaching antisemitic legacy.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay written by Ryan Favro of American Dreaming.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify.

I once witnessed someone get radicalized into vicious antisemitism.

Shaun (not his real name) and I were both active in an online community where politics was often discussed, and I observed, over the course of several months, this young man get led down a dark path to conspiratorial anti-Jewish hate.

Prior to his transformation, Shaun had been a run-of-the-mill Christian conservative with an affinity for the Jewish People. He had even visited Israel and uploaded YouTube videos of his sightseeing.

Shaun faced a number of antisemitic ideologues — if not full-blown neo-Nazis, as near as makes no difference — each armed with just enough truth to be dangerous. They sought to convince him that “The Jews” were a menacing, corrupt, and evil people with sinister and far-reaching influence throughout society — specifically the world of finance.

These extremists pointed to many influential Jewish bankers both in history and today, arguing that Jews have controlled international banking for centuries. They called attention to the disproportionality of the global Jewish population versus their presence in finance, also highlighting average Jewish income versus non-Jewish.

Whereas historical Nazis were fixated on racial antisemitism — of the Jews as impure, verminous, subhuman untermenschen — these neo-Nazis focused primarily on economics and demography. And in so doing, they told no outright falsehoods.

Every source they linked to was reputable. Every fact they cited was technically true. There were myriad lies of omission, as we will see, but Shaun was unaware of that. These economic antisemitic arguments were what drew him in, and over time convinced him that Jews were a threat to White people due to their supposed financial control over the world.

I made numerous attempts to reach out to Shaun, to explain to him that he was being misled, and to try to pull him back from the brink. I was too late. Once he had been radicalized, Shaun was beyond reason and wholly unreceptive to my efforts. It was as though a powerful virus had taken root in his mind, and no treatment — no facts, arguments, or moral appeals — could wipe it out. But this virus can be inoculated against.

The education systems of many Western nations have failed to adequately teach the history necessary to address economic-based antisemitism, exposing a vulnerability that leaves people susceptible to anti-Jewish rabbit holes.

Our existing education focuses on the Holocaust, and the Nazis’ pseudoscientific racism and conspiracy theories. Crucial though that is to teach, it does not take into account of the history of medieval usury laws and their long-reaching antisemitic legacy. This is what needs to change.

Behind the gaudy façade of absurd Nazi racial “science” lies a more pernicious economic current tracing back to the medieval era whose ripples can still be felt today. When an antisemite indicates the prevalence of Jews in banking, the media, and other professions, despite their small population size, with receipts to back it up, most people do not have the wherewithal to rebut them.

Picture a high school student or 20-something exposed to these arguments online with bigoted extremists. Today’s student lacks the necessary knowledge to withstand the onslaught of points trotted out by the antisemite, who will have sources for most of their initial claims. The young person would see that the bigot is not lying when they call attention to the many Jews in finance, as well as the existence of famous Jewish banking families such as the Rothschilds.

By the time the antisemite slyly inserts their own conspiratorial narratives and inductive leaps, they have already penetrated past their interlocutor's outer shell of skepticism.

Here is the uncomfortable truth: Jews, though very few in number, have been and remain considerably overrepresented in finance and other industries. This is what the Nazis said proved that Jews controlled the economics of the world, and what their modern-day knockoffs echo. How should educators address this?

Moreover, what should teachers have learned to be able to address the antisemitic trope that Jews run banking? This is a longstanding antisemitic attack that predates Nazism.

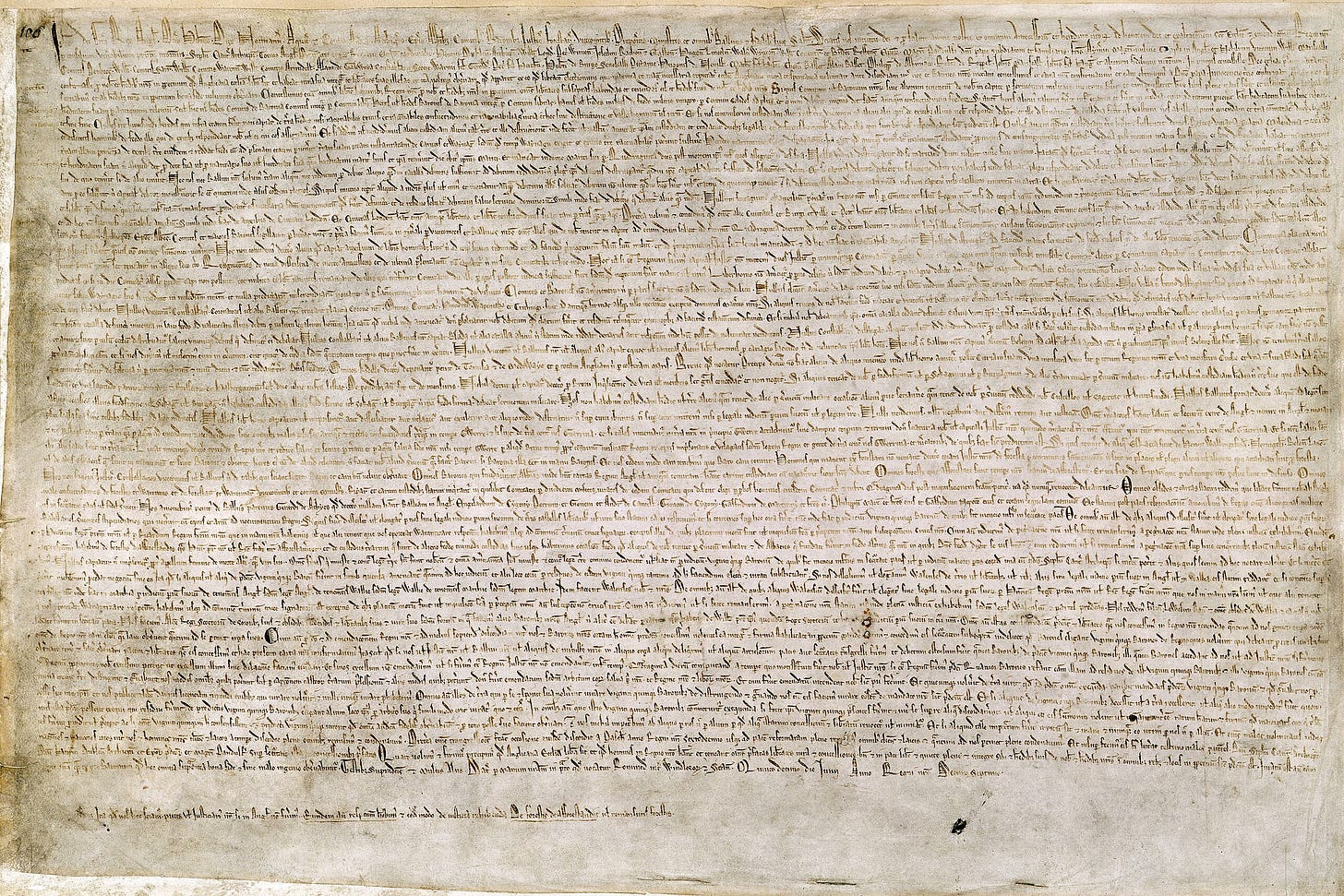

Now that we see that there is an economic phenomenon at hand, we must examine the origin: Medieval usury laws. And in order to do so, our first stop takes us all the way back to the Iron Age.

The Evolution of Usury Laws

All three of the Abrahamic religions, starting with Judaism, followed by Christianity, and then Islam, forbid the practice of usury. In its original sense as viewed by these religions, usury referred to the of lending money with interest, specifically to other members of one’s own religion. This was reflected in the laws that governed European nations as Christianity spread across the continent.

The successes of the Abrahamic faiths — especially of the Jewish sect that became Christianity — brought a sense of both closeness and rivalry between Jews and Christians in medieval Europe. Early on, Jews were seen by Christians as brothers and sisters, albeit those who failed to place their faith in Jesus.

In time, the image of the Jew as a wayward relative morphed into Jews as Christ-killers. And, as a minority in every European country in which they lived, Jews were subject to many forms of bigotry and discrimination, both official and unofficial.

Christian authorities established ghettos in many cities. Throughout Europe, Jews were often denied citizenship, barred from government positions, blocked from trade guilds, and restricted from entry into various lucrative industries, often including prohibitions on land ownership.1

Usury laws were widespread in medieval Europe, but they were not strictly enforced at first. In the 11th and 12th centuries, there were Christian moneylenders just as there were Jewish ones. This changed in the beginning of the 13th century, when the Catholic Church began seriously cracking down on Christian usury.

The height of the anti-usury campaign was the result of the Council of Vienne of 1312-1313, in which the Church equated the sin of usury to heresy and sexual perversion. Anyone associated with Christians found guilty of usury, including wives, business partners, lawyers, and other associates could be implicated.2

Punishments for usurers included paying full restitution and forced penance, alongside the threat of excommunication. The social stigma associated with being a convicted usurer was also particularly severe.3

With many other avenues closed to them, finance became one of the only lucrative professions available to Jews. And with the Church’s escalation of penalties on Christians for practicing usury, a precipitous decrease in Christian moneylenders led to a corresponding increase in Jews entering that field. As a more commercial economy developed in Europe, these societies became increasingly reliant on the credit provided by Jewish moneylenders.4

While the Church imposed social and legal penalties on Christians for usury, the same did not apply for Jews. One reason is that Jews, as non-Christians, largely fell outside the purview of such theocratic laws.

Another reason was that secular rulers protected and supported Jewish moneylending, given its economic importance, and the fact that no one else was allowed to do it. It likewise became common practice for popes to condone Jewish financiers as long as the interest charged was not deemed excessive.

‘Servants of the Royal Chamber’

Raising tax revenue was a consistent headache for the monarchies in 13th century Western Europe, since it required the support of the nobility and was typically reserved only for times of emergency.

The monarchies, whose system of taxation had not kept pace with the changing economic paradigms, had enormous difficulty directly taxing the growing commercial economy in the way that they long had done for land ownership.

But since much of this commerce ran through Jews, as moneylenders, the monarchies developed arrangements for taxing Jews as a way of capturing this lost revenue. One such was the creation of a status for Jews called servi camerae regis (“servants of the royal chamber”).

This identified Jews as serving a monarchy by providing taxation. In practice, the relationship between the monarchies and their Jewish populations was tense. During economic downturns, or when the monarchy struggled with its finances, antagonism towards Jews would intensify from the Christian population, resulting in expulsions of Jews across Western Europe, among other mistreatments.

Stereotypes of Jews as greedy usurers rose in tandem with their proliferation in finance, and continued after medieval times, such as with Martin Luther’s “On the Jews and Their Lies” (1543), and the character Shylock in William Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice” (1600).

At the same time, Christian societies in Europe sought the help of Jews to improve commerce, such as Poland in the mercantile period, resulting in an influx of Jewish immigration. Wealthy Jews in Poland served nobles by managing their estates, thereby coming to exercise power over many people, which engendered significant resentment.

Similarly, the rise of the “court Jew” in Germany — Jewish financiers among a small banking elite that emerged in the mercantile era — provided financial services to royalty and nobility in exchange for social privileges. This provoked hostility not only among Christians, but also by Jewish merchants and craftsmen.56

A Fuller Picture

Jews, like all peoples, have never been a monolith. Court Jews were notable, but few in number, and in the 18th century, an estimated 80 percent of Jews in German-speaking Europe lived in poverty, facing limitations on their freedom of movement and right to earn a living.

In the 19th century, major changes occurred in Central Europe after Christian religious laws restricting Jewish employment opportunities were removed, opening a path to high upward mobility.

According to historian Richard S. Levy, these newly unencumbered Jews became “Contributors to the arts and sciences, consumers of higher education, accumulators of wealth, innovators of business, revolutionizers in media, leaders of political parties and social movements, and holders of public offices.”

German Jews so prospered in the 19th century that Jews living in Frankfurt am Main paid four times more taxes than Protestants, and eight times more than Catholics. In the 1880s, Jews comprised nine percent of university students in Prussia. By 1900, one third of the student body at the University of Vienna was Jewish. Even with these successes, however, many Jews still lived in poverty.

Beginning with the rise of Jews as moneylenders in medieval Europe due to Christian usury laws and restricted opportunities, Jews became prominent players in finance, and with generations of sons following in their fathers’ footsteps, we can still see its reverberations today.

The resentment of a Christian-majority population toward a Jewish minority over their economic and social success, deemed to be at Christians’ expense, has formed a key theme in the antagonism towards Jews ever since.

Over the centuries, this would evolve and eventually take on a racial rather than religious basis in the 19th century, culminating with Nazism in the 20th. And it all stems from circumstances set up by antisemitic medieval Christian authorities, in which Jews behaved, as all beleaguered ethnic minorities do, by playing the hand they were dealt.

What happened to Shaun could happen to anyone. He was lured into antisemitism with contextless half-truths that he was ill-equipped to see through. Young people engaged in online political discussions will invariably confront antisemites alleging that Jews control the world, pointing out the many Jews in banking and other high places.

It is our responsibility to see the public inoculated against these conspiracy theories. If Shaun had been better prepared going in, I do not believe he would have succumbed to the arguments he faced. It is not enough to simply teach that hating Jews is wrong — we must explain why the specific reasons antisemites cite for their hatred make no logical or historical sense.

And to do that, we must include the history and legacy of medieval usury laws in educational curriculums.

“Anti-Semitism in medieval Europe.” Britannica.

Johnson, Noel D. and Koyama, Mark. “Persecution and Toleration: The Long Road to Religious Freedom.” Cambridge University Press. 2019.

Wood, Dianna. “Medieval Economic Thought.” Cambridge University Press. 2002.

Johnson, Noel D. and Koyama, Mark. “Persecution and Toleration: The Long Road to Religious Freedom.” Cambridge University Press. 2019.

Karp, Johnathan. “Antisemitism in the Age of Mercantilism.” Oxford University Press. 2010.

Karp, Johnathan. “Antisemitism: A History.” Oxford University Press. 2013.

Is there anyone out there who would like to work with me on a big piece comparing enlightenment values to Islamist Hamas' values, I mean a point by point walk through and comparison, one of of those long complex pieces that most won't read haha. I think one point people don't realize is that everywhere the Palestinians go they cause problems, their culture (which evolves out of values) is Islamist and largely radicalized, and just as an individual cannot flourish when they are fixated on grievances, and/or when they are chronically unemployed they cannot succeed.

A key point to add is that the whole world benefits from the existence of the finance industry, through provision of resources for investment and saving. The resentful idea that financial profit is harmful is wrongly grounded in emotion rather than reason.