There is no such thing as a 'typical' Jew.

In our post-October 7th world, the need for Jewish diversity has never been more crucial.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

A friend of mine who also lives in Israel just told me a story.

Recently, he went to shoot some hoops at a local basketball court in New York City and encountered a young Black man there.

They started talking and it turns out the young man is a professional basketball player who had just returned to the U.S. after playing for a team in Shanghai. Before then, he played for Ironi Ness Ziona, a professional basketball club based in Ness Ziona, Israel (about 20 minutes southeast of Tel Aviv).

Turns out, this young man’s mother is Jewish and he grew up with some exposure to Judaism, although not as much as he would have liked. He is now in the process of “making aliyah” (immigrating to Israel and becoming an Israeli citizen).

This story reminded me that there is no such thing as a “typical Jew” — even though many Jews act as if they are “typical Jews” and Jews who are unlike them are atypical (i.e. weird, bizarre, inauthentic, inferior).

The notion of a “typical Jew” is not only misleading but also deeply problematic. It assumes a homogeneity that simply does not exist within the Jewish world, a people that is as diverse and multifaceted as any other.

Jews come from different countries, speak different languages, and practice Judaism in various ways. There are Ashkenazi Jews from Europe, Sephardic Jews from Spain and the Mediterranean, Mizrahi Jews from the Middle East and North Africa, and Ethiopian Jews from Africa, among others. Not to mention Indian Jews, Nigerian Jews, and so forth.

Each of these groups has its own unique customs, traditions, and interpretations of Judaism. This diversity extends beyond just religious and cultural practices; it also includes differences in political beliefs and social values. But one thing is unequivocally true amongst Jews, no matter their place of birth, ethnicity, customs, traditions, and interpretations: When one Jew meets another Jew, there is an immediate inseparable bond.

At the same time, many Jews (particularly those of the “liberal” ilk) champion diversity in the countries they live, but look down upon it (implicitly, oftentimes) within the Jewish world. Any Jew who does not look or act like them is less deserving of their respect, so to speak.

A quick Jewish history lesson reveals the unfortunate reality that Jews have never fully been “united” in how we all perceive Jewishness and practice Judaism. From the earliest days of Jewish existence, diversity in belief, practice, and identity has been a defining characteristic of the Jewish People. This diversity stems from the various ways Jews have understood their relationship with God, their interpretation of religious texts, and their adaptation to the cultures and societies in which they lived.

One of the earliest examples of this diversity can be seen in the division between the Sadducees and the Pharisees during the Second Temple period. The Sadducees, who were generally associated with the priestly class and the Temple rituals, had a more literal interpretation of the Torah and rejected Oral Law (the “unwritten Torah”). In contrast, the Pharisees emphasized Oral Law’s importance and believed in the development of Jewish law through interpretation and debate.

Throughout the centuries, as Jews spread across the globe and encountered different cultures, these variations only deepened. The development of Ashkenazi, Sephardic, Mizrahi, and other Jewish traditions illustrates the extent to which geography, history, and local customs have influenced Jewish practice.

For example, Ashkenazi Jews in Europe developed their own liturgical rites, languages like Yiddish, and unique customs distinct from those of Sephardic Jews, who were influenced by the cultures of the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean. Yemenite Jews learned to read the Torah upside down and sideways, since traditional books were very scarce.

In more recent history, the rise of different Jewish denominations, such as Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, and Reconstructionist Judaism, further underscores the diversity of Jewish thought and practice. These movements emerged in response to modernity and the varying ways Jews sought to maintain their identity in rapidly changing societies. Each denomination reflects a different understanding of Jewish law, tradition, and the role of Jews in the modern world, leading to significant differences in religious observance and community life.

Whether it is on the basis of religious observance (or lack thereof), or related to ethnicities, nationalities, socioeconomic factors, stereotypes, Israel and Zionism, the Holocaust, and so on, let’s be honest: Jews have a habit of judging other Jews. This is not just my observation; it is backed by moral psychology, which suggests that people are more likely to judge those in their own circles.

According to Jonathan Haidt, a Professor of Ethical Leadership at New York University, human nature is not just intrinsically moral; it is also intrinsically moralistic, critical, and judgmental. This enabled human beings — but no other animals — to produce large cooperative groups, tribes, and nations without the glue of kinship.

At the same time, moral psychology virtually guarantees that our cooperative groups will always be cursed by moralistic strife. We all know the age-old Jewish joke: “Two Jews, three opinions.”

The problem is when competing ideologies are knocked out of balance, which is the premise of righteousness, a word that once meant “just, upright, virtuous.” Nowadays, this word has strong religious connotations because it is usually used to translate the Hebrew word tzedek (justice).

Jewish diversity is not a weakness but a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the Jewish People. It highlights the capacity of Judaism to evolve and thrive in a multitude of environments while still maintaining a shared sense of identity. Though the Jewish community may not be united in how it perceives Jewishness or practices Judaism, this multiplicity of voices and perspectives has enriched Jewish life and ensured its continuity across millennia.

Now, in our post-October 7th world, the need for Jewish diversity has never been more crucial. And all we have to do is look at the State of Israel to understand how Jewish diversity generates positive outcomes against all odds.

From the outside looking in, many people think that Israel is a “White” country made up of mostly White-looking Jews. Indeed, a healthy majority of Israelis are not “White.” Leading up to and after the country’s establishment in 1948, Jews from literally all across the world immigrated here, and present-day Israeli society has one of the highest interethnic marriage rates by a long shot.

With each “type” of Jew that immigrated to Israel, the country developed another layer to deal with ever-present external threats. For example, Middle Eastern Arabic-speaking Jews, often referred to as Mizrahi Jews, have played a significant in Israel’s military and intelligence efforts, particularly in conflicts involving Israel’s Arab neighbors. Their deep understanding of Arab culture, language, and customs has been an invaluable asset in Israel’s defense strategy, especially during the early years of the state.

During the 1948 War of Independence and subsequent conflicts, many Mizrahi Jews, who had emigrated from countries like Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, and Syria, brought with them not only their native Arabic language skills but also an intimate knowledge of the region’s socio-political landscape.

These skills were critical in gathering intelligence, conducting espionage, and understanding the motivations and tactics of Israel’s enemies. For instance, Mizrahi Jews were instrumental in operations where knowledge of local dialects and customs allowed Israeli forces to infiltrate enemy lines, gather crucial information, and disrupt enemy activities.

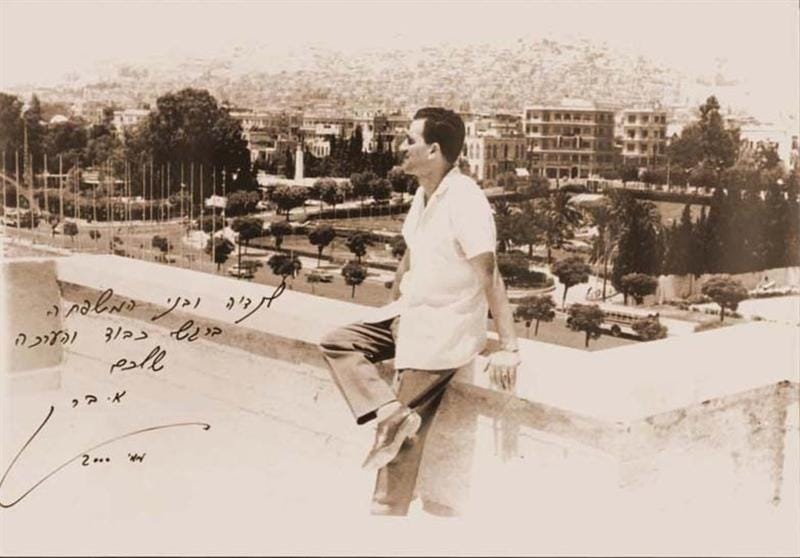

Additionally, their ability to blend into Arab societies enabled them to undertake covert operations that would have been impossible for those without such backgrounds. Let’s recall the phenomenal story of Elie Cohen, an Egyptian-born Israeli spy who infiltrated the highest levels of Syria’s government during the 1960s and went on to provide an extensive amount of intelligence to the IDF that factored into Israel’s surprising success during the 1967 Six-Day War.

At the same time, European Jews who immigrated to Israel typically brought more advanced forms of technology, medicine, and infrastructure — positioning the Jewish state to become far more modern than the rest of the Middle East.

Dr. Israel Kligler, a Jewish microbiologist, eradicated malaria from British-era Palestine during the 1920s. Ironically, this development caused a major Arab population increase in this part of the region; local Arabs said that Zionists made the land “livable” and came to take advantage of new work opportunities provided by the growing population.

More recently, Israel’s diversity has led to disproportional cultural breakthroughs, making Israeli technology, medicine, cuisine, TV and film, and even fashion fairly recognizable in many places across the world.

If we look at a person solely on an individual basis, we are probably missing a lot of their story. International bestselling author Malcolm Gladwell suggests we should be looking at people more broadly because of the “coupling” phenomenon.

In short, “coupling” means that people act or behave according to their environment, and according to what is and is not available to them (e.g. tools, knowledge, education).

Here’s a funny, but true, example of “coupling”: Israelis are notorious for not standing in line. Shachar Hason, one of Israel’s top standup comedians, jokes about this, saying: “I was performing in Germany, and a German woman in the audience said to me, ‘I love Israel, but I don’t understand why Israelis don’t stand in line.’ I told her, ‘I’m sure you remember the last time Germans told us to stand in line…’”

All jokes aside, standing in line is not an Israeli thing; it is an Israel thing, an environment thing. When Israelis travel abroad, they have no problem standing in line. But in Israel, the environment, the culture, is such that lines are effectively optional, and Israelis (the humans that they are) conform accordingly.

When contemplating “atypical” Jews, remember that they are a product of their environment, so aiming to better understand their surroundings will go a long way in better understanding them as a person and as a Jew.

When Avraham Infeld was President of the Jewish organization, Hillel International, he would travel around the world meeting with Jewish students, and he would bring a chart that was divided into three columns.

The top line listed: apples, oranges, bananas. Down the side read: lettuce, tomatoes, cucumber. A final line asked students to fill in the blanks: Jew, it listed, and then two blank spots. In other words, what is to a Jew as an apple is to an orange?

In the United States, more than 200,000 responses were unanimous — Jew, Christian, Muslim — suggesting Judaism is a religion. But in 40,000-plus responses from Israelis, not one said Jew, Christian, Muslim. Instead, they said Arab or Italian or American, implying that Judaism is a nationality. When it came to Russian Jews, 10,000 responded this way: Jew, non-Jewish is a Russian.

“What does this all tell us?” Infeld rhetorically asked. “I’ll tell you what this tells us: the Jewish People are totally confused about our identity!”

Judaism runs so vast and deep — from religion and spirituality, to wisdom and philosophy, culture and lifestyle, travel and tourism, peoplehood and community, history and tradition, Israel and Zionism.

We each have our own image of Judaism, what it represents for us, and the value and meaning it has added to our lives. All of these perceptions and connotations are a combination of what we have (and have not) been exposed to; of our past and current interests, passions, needs, desires, and worldviews; of where and in what generation we were born into; and so forth.

For example, we know that Jews who grew up directly against the backdrop of the Holocaust are far more likely to unconditionally support the State of Israel, compared to younger Jews born into a world with an established and strong State of Israel, yet one often (and baselessly) painted as the bullying aggressor by much of the mainstream media.

We know that non-Israeli Jews cohabitating in the Diaspora have a much different lived experience than Israeli Jews, who have experienced genocidal war after war essentially every decade, sometimes multiple wars in a single decade.

Heck, we know that Israelis who predominantly live in the center of Israel have a much different lived experience than Israelis who reside in one of the border towns of the Gaza Strip, or of Lebanon and Syria in Northern Israel, who in turn have a much different lived experience than Israelis who live in Judea and Samaria (also known as the West Bank).

If we embrace Judeo-diversity — that people experience and interact with Judaism in many different ways, and that there is no one “right” or “typical” way of being and doing Jewish — we can profoundly enhance the Jewish story.

And, following October 7th, this seems like the only path forward to creating a more promising Jewish future.

The one type of Jew not discussed is the anti-Zionist Jew that, unfortunately, is growing more common among younger Jews of the “liberal ilk.” I consider them to be atypical, and we most definitely do not need that type of diversity.

Our cultural and ethnical diversity is a product of the diaspora. It is how we survived. But our strength is not in our diversity. It is in our unity. E pluribus unum would be good motto for Jews post 10/7.