Why Jews Are Divided by Politics and Religion

Or, the reasons that it’s so hard for us Jews to get along.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free and zero-advertising for all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

When it comes to the Jewish People, no small group is more diverse ethnically, culturally, attitudinally, and religiously.

Moses doesn’t use the word Torah in the last of the 613 commandments. Rather, he employs the Hebrew word shirah (song) because, in this respect, Torah is like music: Its greatest beauty lies in complex harmonies.

And, as the legendary rabbi Netziv wrote in his commentary on the Tower of Babel, uniformity of thought is not a sign of freedom, but its opposite.

Yet, despite sharing the same prefix, unity is not uniformity. If uniformity asks, “Can we all agree?” then unity posits: “Can we all get along?”

Following the death of King Solomon, circa 931 BCE, a civil war divided our ancestors into two kingdoms, Israel and Judah. The prophets foretold that, in Messianic times, we would reunite into a single nation again. The Ten Tribes of Israel were “lost” in the Assyrian exile, and we are descended from Judah, which is why we’re called Jews.

When our modern state was founded in 1948, we didn’t call it Judah; we called it Israel, representing our spirit of unity, but also our tendencies to argue. Israel means “to wrestle with God.”

Does family come first?

Dr. Erica Brown, a vice provost at Yeshiva University, grew up as an Ashkenazi Jew in a predominantly Sephardic New Jersey town. She doesn’t look Syrian, but when people asked Brown if she was, she would joke about being a “wannabe.”

“It was not because I saw myself ritually or materially like the Jews around me, but I saw something in the Syrian culture that made me very envious,” wrote Brown. “The community had a certain kind of intimacy, an easy sort of connectedness that allowed people with very different customs and behaviors to sit at the same Shabbat table without judgment.”

At the time, only a small percentage of the Jews in her town were really Sabbath observant, but almost everyone Brown knew kept a kosher home, enjoyed Friday night dinner, and observed the Jewish holidays in some way. Rumor had it that every woman even went to the mikvah.

“As I grew older and became more of a student of Jewish history, I understood that this kind of acceptance was common in other Sephardic communities,” wrote Brown. “Certain commandments were central to maintaining the integrity of one’s Jewishness, but the bonds of family and community were even stronger than any distance created by differing ritual practices or levels of observance.”

Unity was paramount, Brown said, and in order to achieve it, certain individual predilections had to be compromised for the ultimate sake of the community’s wholeness.

“The community is your family, and everyone in a family does not look alike or behave alike, but there is room at the table for them all,” she wrote. “I was not seeing that in most of the Ashkenazic communities I lived in or visited. Often very small differences of ritual practice created what seemed like untraversable distances among Jews. The Ashkenazi air always seems thick with judgment: too much to the right of me, too much to the left of me, not close enough for friendship. Family? Forget about it.”

Brown was quick to point out that she was not offering a sociological study of religion, but simply her “naïve childhood observances” of the way different communities function and achieve (or miss) the goal of unity.

“Even so, I still believe the only way unity and true ahavat Yisrael (to love a fellow Jew) can be achieved is to believe in one’s heart and to illustrate through one’s actions that family comes first,” Brown wrote. “We are immensely lucky to be part of an extended family that is thousands of years old. Religion is a critical glue in keeping family together, but we have to remember that it is not the only glue. I mean this as no heresy. Being Jewish is a faith, a nationality, an ethnicity, and a layer of identity. Whichever layer you choose as your outer garment determines much of what lies beneath.”

Introduction to Moral Psychology

Morality is the extraordinary human capacity that made civilization — and as an extension, Judaism — possible. It also made two of the most important, vexing, and divisive topics in human life: politics and religion.

“Etiquette books tell us not to discuss these topics in polite company, but I say go ahead,” wrote Jonathan Haidt, a professor of ethical leadership at New York University. “Politics and religion are both expressions of our underlying moral psychology, and an understanding of that psychology can help to bring people together.”

Through a firmer grasp on moral psychology, Haidt says that we can drain some of the heat, anger, and divisiveness out of these topics — and replace them with a mixture of awe, wonder, and curiosity.

So, what is moral psychology?

Moral psychology investigates human functioning in moral contexts, and asks how these results may impact debate in ethical theory, through thought experiments, responsibility, character, egoism versus altruism, and moral disagreement.

For philosophers, the special interest of this interdisciplinary subject lies in the ways moral psychology may help adjudicate between competing ethical theories. Equally important are normative questions having to do with how well a theory fares when compared to important convictions about such things as justice, fairness, and the good life.

According to Haidt, human nature is not just intrinsically moral; it’s also intrinsically moralistic, critical, and judgmental. This enabled human beings — but no other animals — to produce large cooperative groups, tribes, and nations without the glue of kinship. At the same time, moral psychology virtually guarantees that our cooperative groups will always be cursed by moralistic strife.

“Some degree of conflict among groups may even be necessary for the health and development of any society,” Haidt wrote. “When I was a teenager I wished for world peace, but now I yearn for a world in which competing ideologies are kept in balance, systems of accountability keep us all from getting away with too much, and fewer people believe that righteous ends justify violent means. Not a very romantic wish, but one that we might actually achieve.”

The problem is when competing ideologies are knocked out of balance, which is the premise of righteousness, a word that once meant “just, upright, virtuous.” Nowadays, this word has strong religious connotations because it is usually used to translate the Hebrew word tzedek (justice), a common term in the Bible. Tzedek is often used to describe people who act in accordance with God’s wishes, but it is also an attribute of God and of God’s judgment of people (which is often harsh but always thought to be just).

The link between righteousness and judgmentalism is captured in some modern definitions of righteous, such as “arising from an outraged sense of justice, morality, or fair play.” This linkage also appears in the term self-righteous, which means “convinced of one’s own righteousness, especially in contrast with the actions and beliefs of others; narrowly moralistic and intolerant.”

According to Haidt, our obsession with righteousness — leading inevitably to self-righteousness — “is the normal human condition. It is a feature of our evolutionary design, not a bug or error that crept into minds that would otherwise be objective and rational.”

But, what happens when this “normal human condition” creates friction between different parts of, say, the greater Jewish “family” and does terrible damage? What happens when this friction is not based on who’s right and who’s wrong, but on differing beliefs between right and wrong? And what happens when both sides are actually right about many of their central beliefs and concerns?

Why It’s So Hard for Jews to Get Along

There are three main reasons why Jews are divided by politics and religion, but it begins with the realization that we are all self-righteous hypocrites.

The starting point is our classic Jewish resources, which are quite clear: Jews were exiled from Jerusalem and the Second Temple was destroyed 2,000 years ago, not because of the Roman legion’s insurmountable strength, but because we Jews “couldn’t get along with each other within,” former Israeli Member of Knesset Dov Lipman told me, adding:

“There’s an amazing power when we’re unified and able to function together as a people, and once we lose that, our enemies that always seek to destroy us are able to come in and make that happen.”

As the eighth-century Chinese Zen master Sen-ts’an wrote:

“The Perfect Way is only difficult

for those who pick and choose;

Do not like, do not dislike;

all will then be clear.

Make a hairbreadth difference,

and Heaven and Earth are set apart;

If you want the truth to stand clear before you,

never be for or against.

The struggle between ‘for’ and ‘against’

is the mind’s worst disease.”

I am not suggesting we should live our lives according to this “Perfect Way.” In fact, I believe that a world without moralism, gossip, and judgment would quickly decay into chaos. But if we want to understand ourselves, our divisions, our limits, and our potential, we need to step back, drop the moralism, apply some moral psychology, and analyze the games we’re all playing.

Let us now examine the psychology of this struggle between “for” and “against.” It is a struggle that plays out in each of our righteous minds, among all of our righteous groups — and it is the three main reasons why Jews are divided by politics and religion:

1. Social Intuitionism

In moral psychology, “social intuitionism” is a model which proposes that moral positions are often non-verbal and behavioral. Often they are based on “moral dumbfounding,” in which people have strong moral reactions, but fail to establish any kind of rational principle to explain their reaction.

Social intuitionism proposes four main claims about moral positions, that they are:

Primarily intuitive (“Intuitions come first.”)

Rationalized, justified, or otherwise explained after the fact

Taken mainly to influence other people

Often impacted and sometimes changed by discussing such positions with others

If you believe that moral reasoning is something we do to figure out the truth, you’ll be constantly frustrated by how foolish, biased, and illogical people become when they disagree with you. But if you think about moral reasoning as a skill we humans evolved to further our social agendas — to justify our own actions and to defend the groups we belong to and associate with — then things will make a lot more sense.

“Moral thinking is more like a politician searching for votes than a scientist searching for truth,” Haidt wrote. “Keep your eye on the intuitions, and don’t take people’s moral arguments at face value. They’re mostly post-hoc constructions made up on the fly, crafted to advance one or more strategic objectives.”

Haidt also suggests that we have unconscious intuitive heuristics (i.e. mental shortcuts) which generate our reactions to morally charged-situations, and underlie our moral behavior. When people defend their moral positions, they often miss (if not hide) the core premises and processes that actually led to their conclusions.

This could explain why the concept of God is divisive in Judaism. It’s not that believing in God is “good” or “bad” and “right” or “wrong” — but rather, it creates a disconnect between Jews who devoutly believe in God and rationalize their behaviors as such (a version of social intuitionism), versus Jews whose belief in God is flimsy or outright nonexistent. This is why the latter group of people finds it difficult to connect with the former group, which behaves in the name of or because of God.

Furthermore, Haidt’s model states that moral reasoning is more likely to be interpersonal than private, reflecting social motives (i.e. reputation, alliance-building) rather than abstract ones. Hence why moral reasoning is highly biased by two sets of motives, which Haidt labels “relatedness” motives (relating to managing impressions and having smooth interactions with others) and “coherence” motives (preserving a coherent identity and worldview).

However, interpersonal discussion and, on rare occasions, private reflection can activate new intuitions, which are then carried forward into future judgments.

The central metaphor is that the mind is divided, like a rider on an elephant, and the rider’s job is to serve the elephant. The rider is our conscious reasoning — the stream of words and images that hogs the stage of our awareness. The elephant is the other 99 percent of mental processes — the ones that occur outside of awareness, yet actually govern most of our behaviors.

Haidt developed this metaphor in his book, The Happiness Hypothesis, where he described how the rider and elephant work together, sometimes poorly, as we stumble through life in search of meaning and connection. Such a premise explains why it seems like everyone (else) is a hypocrite, why political partisans are so willing to believe outrageous lies and conspiracy theories, and how we can better persuade people who seem unresponsive to reason.

2. Moral Foundations Theory

In contrast to the dominant theories of morality in psychology, the anthropologist Richard Shweder developed a set of theories emphasizing the cultural variability of moral judgments. But he also argued that different cultural forms of morality drew on “three distinct but coherent clusters of moral concerns,” which he labeled as the ethics of autonomy, community, and divinity.

Shweder’s approach inspired Haidt to begin researching moral differences across cultures, and the latter began to devote attention to intuitions’ sources, which he and his team believed underlay moral judgments. In 2004, Haidt and Craig Joseph proposed that all individuals possess four “intuitive ethics” stemming from the process of human evolution, as responses to adaptive challenges. They labeled these ethics: suffering, hierarchy, reciprocity, and purity.

Moral Foundations Theory explains the origins of and variation in human moral reasoning on the basis of innate, modular foundations. The theory initially proposed five foundations (and Haidt later added a sixth one, Liberty/Oppression) —

Care/Harm

Fairness/Cheating

Loyalty/Betrayal

Authority/Subversion

Sanctity/Degradation

“The righteous mind is like a tongue with six taste receptors,” Haidt wrote.

According to the theory, differences in people’s moral concerns can be described across these five moral foundations: Individualizing cluster of Care and Fairness; and the group-focused Binding cluster of Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity.

Haidt’s field work in Brazil, Philadelphia, and India showed that moralizing indeed varies among cultures, but less than by social class (e.g. education) and age. Working-class Brazilian children were more likely to consider both taboo violations and infliction of harm to be morally wrong, and universally so. Members of traditional, collectivist societies, like political conservatives, are more sensitive to violations of the community-related moral foundations.

Adult members of so-called WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) societies are the most individualistic, and most likely to draw a distinction between harm-inflicting violations of morality and violations of convention.

A recent large-scale analysis of sex differences based on the initial five moral foundations suggested that women consistently score higher on Care, Fairness, and Sanctity across 67 cultures. However, Loyalty and Authority were shown to have negligible sex differences, highly variable across cultures. Ultimately, global sex differences in moral foundations are larger in individualistic, Western, and gender-equal cultures.

Researchers postulate that the moral foundations arose as solutions to problems common in the ancestral hunter-gatherer environment, in particular intertribal and intra-tribal conflict. The three foundations emphasized more by conservatives (Loyalty, Authority, Sanctity) bind groups together for greater strength in intertribal competition, while the other two foundations balance those tendencies with concern for individuals within the group. With reduced sensitivity to the group moral foundations, progressives tend to promote a more universalist morality.

Haidt and Joseph also claimed that each of the ethics formed a cognitive module whose development was shaped by culture, writing that each module could “provide little more than flashes of affect when certain patterns are encountered in the social world,” while a cultural learning process shaped each individual’s response to these flashes.

Although every society constructs its own morality, it is the varying weights that each society allots to these universal foundations which creates variety. Haidt likens moral foundation theory to an “audio equalizer,” with each culture adjusting the sliders differently.

“A dictum of cultural psychology is that ‘culture and psyche make each other up.’ In other words, you can’t study the mind while ignoring culture, as psychologists usually do, because minds function only once they’ve been filled out by a particular culture,” Haidt wrote. “And you can’t study culture while ignoring psychology, as anthropologists usually do, because social practices and institutions (such as initiation rites, witchcraft, and religion) are to some extent shaped by concepts and desires rooted deep within the human mind.”

What’s more, the usefulness of moral foundations theory as an explanation for political ideology is supported by longitudinal data that suggests political ideology predicts subsequent endorsement of moral foundations, but moral foundations endorsement does not predict subsequent political ideology.

Using the Moral Foundations Questionnaire, Haidt and Jesse Graham found that libertarians are most sensitive to the proposed Liberty foundation, liberals are most sensitive to the Care and Fairness foundations, and conservatives are equally sensitive to all five foundations. Because members of two political camps are to a degree blind to one or more of the moral foundations of the others, they may perceive morally driven words or behavior as having another basis — at best self-interested, at worst evil, and thus demonize one another.

Haidt and Graham suggest a compromise can be found to allow liberals and conservatives to see eye-to-eye, by using these foundations as “doorway” to allow liberals to step to the conservative side of the “wall” put up between these two political affiliations on major political issues (i.e. legalizing gay marriage).

If liberals try to consider the latter three foundations in addition to the former two (therefore adopting all five foundations like conservatives for a brief amount of time), they could understand where the conservatives’ viewpoints stem from, and long-lasting political issues could finally be settled.

Haidt himself acknowledged that, while he’s been a liberal all his life, he’s now more open to other points of view.

3. The Binding and Blinding of Morality

Human nature was produced by natural selection working at two levels simultaneously.

First, individuals compete with individuals in every group, and we are the descendants of primates who excelled at such competition. This gives us the ugly side of our nature, the one that is usually featured in books about our evolutionary origins.

“We are indeed selfish hypocrites so skilled at putting on a show of virtue,” Haidt wrote, “that we fool even ourselves.”

But human nature was also shaped as groups competed with other groups, a dynamic that has plagued the Jewish world since its origins, and comes to life nowadays through flailing Israel-Diaspora relations, as well as religious denominations such as Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, and so forth. In Israel, the breakdown is often secular versus religious, central Israel versus the “periphery” and, once upon a time, Ashkenazi versus Mizrahi or Sephardic.

As Charles Darwin said long ago, the most cohesive and cooperative groups generally beat the groups of selfish individualists. Darwin’s ideas about group selection fell out of favor in the 1960s, but recent discoveries are putting his ideas back into play, and the implications are profound.

“We’re not always selfish hypocrites,” according to Haidt. “We also have the ability, under special circumstances, to shut down our petty selves and become like cells in a larger body, or like bees in a hive, working for the good of the group. These experiences are often among the most cherished of our lives, although our hive-ishness can blind us to other moral concerns. Our bee-like nature facilitates altruism, heroism, war, and genocide.”

“Once you see our righteous minds as primate minds with a hive-ish overlay, you get a whole new perspective on morality, politics, and religion,” he wrote. “Our ‘higher nature’ allows us to be profoundly altruistic, but altruism is mostly aimed at members of our groups.”

In Haidt’s view, religion is (probably) an evolutionary adaptation for binding groups together and helping them to create communities with shared morality. It is not a virus or parasite, as some scientists (e.g. the “new atheists”) have argued in recent years.

Moreover, some people are conservative, others are liberal (or progressive), and still others become libertarians. People bind themselves into political teams that share moral narratives. Once they accept a particular narrative, they become blind to alternative moral worlds and other ways of thinking, which can make them more dogmatic — and may create a sense of moral superiority or purity, rather than true morality.

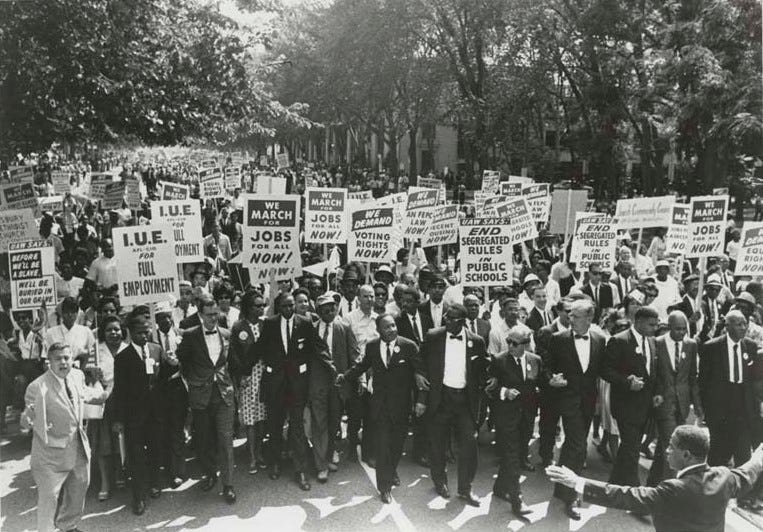

In the early 1990s, Rodney King, a black man, was nearly beaten to death by four Los Angeles police officers. The entire world, seemingly, saw a videotape of the beating, so when a jury failed to convict the officers, their acquittal triggered widespread outrage and six days of rioting in Los Angeles.

Fifty three people were killed and more than 7,000 buildings were torched. Much of the mayhem was carried live by news cameras from helicopters circling overhead. After a particularly horrific act of violence against a white truck driver, King was moved to make his appeal for peace, famously saying:

“Can we all get along?”

King’s appeal is now so overused that it has become a cultural cliché, a catchphrase more often said for chuckles than as a serious plea for mutual understanding and productive relations.

What often goes missing from this overused phrase, however, is King’s follow-up. As he stumbled through his television interview, fighting back tears and often repeating himself, King found these words:

“Please, we can get along here. We all can get along. I mean, we’re all stuck here for a while. Let’s try to work it out.”

You are overthinking this. Some people are more predatory, some are just more submissive by nature. Both groups have their own ways to justify their approach to success and survival. There were Maccabees and there were Shtetl's Jews. I know siblings from an identical backgrounds who have a totally opposite political and social views. Some women will fall on the sword before loosing their honor, some will prostitute themselves in order to survive. In WW2 the Poles sent a cavalry against German tanks and paid dearly for this act of symbolic bravery, the Czechs on other hand decided to outlast the Nazis by surrendering. At the end Nazi Germany lost and was destroyed. Who is to judge.?Sure the environment has an impact, but how do you explain Israelis marching for peace with the Palestinians, while rockets are being launched from Gaza and are falling on their heads ? Many of these marchers for peace were veterans of combat units. I've two dogs, one large who is untrainable, and has a screw you attitude, he likes me, and loves my wife, but he will never change, the other is small and very submissive. They both want to be fed and taken for walks. Not sure if people are much different. Recent study claimed there is a such a thing as leftist DNA, maybe we are predestined in our approach to life.

This is a treatise that needs an in depth study and analysis for a normal person to be able to comprehend it's true meaning!