American Jews are officially dying a fast death.

The Israel-Hamas war has exacerbated this terrible trend, which includes death by assimilation, arrogance, ignorance, and the rise of progressive liberalism among American Jews.

Editor’s Note: In light of the situation in Israel — where we are based — we are making Future of Jewish FREE for the coming days. If you wish to support our critical mission to responsibly defend the Jewish People and Israel during this unprecedented time in our history, you can do so via the following options:

You can also listen to this essay if you prefer:

Or listen on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Spotify

That’s right, the country home to the world’s second-largest Jewish population, and in some ways its most powerful, is rapidly approaching social extinction.

Naturally, this will cause a lot of defensive posturing from American Jews and Jewish Americans, so please bare with me as I explain where I’m coming from and why I’m sounding the alarm, before it quickly becomes too late.

First, you should know that I am an Israeli-American dual citizen who was born to an American mother and Hungarian father in Los Angeles, in 1989. I spent my first 24 years in North America as an American Jew. We were mostly reform Jews, although my dad is part of the conservative Jewish movement.

In my late teenage years, I started getting swept up in many of the travesties that I outline in this essay, and at one point I completely denounced my Jewishness. In 2013, I reluctantly took a free 10-day trip to Israel, called Birthright, only on the grounds that it was an all-expenses-paid-for vacation.

This trip to Israel changed my life, so much so that I didn’t get on the plane back to the United States. A few weeks later, I found an apartment in Tel Aviv, became an Israeli citizen within a few months, and have been living in Israel ever since.

In Israel, I had a Jewish reawakening: I learned Hebrew from scratch, taught myself all of Jewish history, and became very traditional in the cultural and heritage sense. I’m not religious, per se, but I genuinely appreciate a lot of the religious aspects of Judaism.

In Israel, I also noticed that Judaism and Jewishness are, in many ways, completely different from Judaism and Jewishness outside of the Jewish state. This is due to a combination of reasons, such as:

Judaism and Jewishness literally being built-in to Israel

Israel’s diverse ethnic makeup (Mizrahi Jews, Sephardic Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, Ethiopian Jews, et cetera)

The Jewish state’s location, sandwiched between the Middle East and North Africa

Jewish immigration to other countries

Sociology, psychology, education, and centuries of enduring Jewish trauma (which has been psychologically proven to be passed down to subsequent generations)

To be sure, Israel’s versions of Judaism and Jewishness are not anything close to perfect, and there is much that Israeli Jews could learn from Jews in the Diaspora.

Still, the State of Israel has, on the whole, done an indelible job of ensuring Judaism and Jewishness are both alive and well across the country, whereas the United States, and perhaps other parts of the Jewish Diaspora, have been — at least from my vantage point — heading in the wrong directions.

To detail that claim, I’ve broken down this essay into eight sections:

Death by Assimilation

Lack of Knowledge and Effective Education

Growing Arrogance and Ignorance

Jewish Disunification

Jewish Leadership (or Lack Thereof)

How American Jews Are Raised

A Fraught Relationship With Israel and Zionism

The Rise of Progressive Liberalism Among American Jews

I want to preface these eight sections by saying that I am not talking about individual American Jews and specific American Jewish communities. There are many individual American Jews and specific American Jewish communities which have been doing and continue to do great work. This essay is a high-level overview and not meant to be particular about anyone or any group of people within American Jewry.

Additionally, it’s important to note that, while this essay is a damning condemnation of American Jewry, I am not writing off American Jewry. Despite all of this essay’s “chutzpah,” I wrote it to urgently raise awareness about the growing troubles plaguing American Jewry, with the goal of inspiring equally urgent action — at the individual level, the communal level, the regional level, the national level, and the organizational level.

And, finally, to those who can personally relate to various contents of this essay, I urge you to not be ashamed, but to be enlightened. To realize that, while you might be one of millions of Jews in America, Theodor Herzl was also just one of millions when he started promoting the notion of a Jewish state. You have more power than you know, and it starts with assigning great priority and urgency to doing the work, day by day.

Now, without further ado, let’s dive into each of the eight sections:

1. Death by Assimilation

Almost a quarter century ago, a monograph on changing patterns of Jewish identity in America, titled “The Jew Within,” observed a turn away from more collective and communal ways of being Jewish, and a turn toward expressions that are more private and personal, if not highly idiosyncratic.1

Some of these more recent expressions are a logical response to looking at both historical and modern-day antisemitism — and how Jews have coped, survived, and even thrived in the face of incessant persecution, centuries of general oppression and prejudices, and inherited generational traumas.

Many American Jews, for example, responded to antisemitism in the 20th century by attempting to assimilate. They changed their names, altered their noses and hairstyles, married non-Jews, didn’t teach their children traditional Jewish languages, downplayed the communication styles which were perceived to be too loud and expressive, and at times incorporated Christian traditions into religious services (see: Reform Judaism) to minimize their Jewishness.

Many American Jews also shared the anti-oppression emphasis of the political left, and here, too, they assimilated. These Jews believed they would be better off and less likely to be persecuted as Jews if they could show their non-Jewish neighbors that they were just like them, that they could behave in ways that weren’t different from the behavioral patterns of their non-Jewish neighbors, and that they would not insist on specifically Jewish concerns within these leftist organizations and movements.

Another tactic was to immerse yourself in traditional Jewish religious life, or Orthodoxy. While this wasn’t just a response to antisemitism, antisemitism did influence the desire to have as little as possible to do with the painful world and ideas of the non-Jews.

The Zionist approach also attracted a number of Jews as resolution to the centuries-old yearning for the indigenous land from which Jews had been exiled. Underlying this desire, particularly in the post-World War II era, was the notion that creating and maintaining a viable Jewish state was the only real path to safety in a world which had mostly turned a blind eye to eternal antisemitism.

Other Jews have tossed in their lot with the ruling classes. Though some of this may be ideological kinship — given the “rebellious spirit” of Judaism and inherent oppression built into ruling classes — this alliance may be more expedient than a partnership built solely on compatibility and true desire. However, it is an old coping mechanism for some Jews to align themselves with power in the hopes that, when the temperature of antisemitism warms, these alliances will protect them.

In liberal democracies like the United States, some Jews who are Ashkenazi (or European origin) or simply “white-looking” have tried to blend in as “white people,” with the privileges that so-called white people enjoy. By doing so, these Jews have made it exponentially harder to examine either historical antisemitism or the ways in which antisemitism still plays out.

Furthermore, this cloak of whiteness prevents the exploration of Jews as 11 ethnic minorities with a unique history of oppression. And whiteness precludes Jews’ inclusion within a multicultural context where their equally unique and ongoing contributions to the world might be examined.

Without this examination, there is a shroud of ignorance and invisibility around antisemitism. If non-Jews do not understand or recognize this phenomenon, not only is the possibility of it reoccurring great, but Jewish anxiety and vulnerability will be perpetuated.

2. Lack of Knowledge and Effective Education

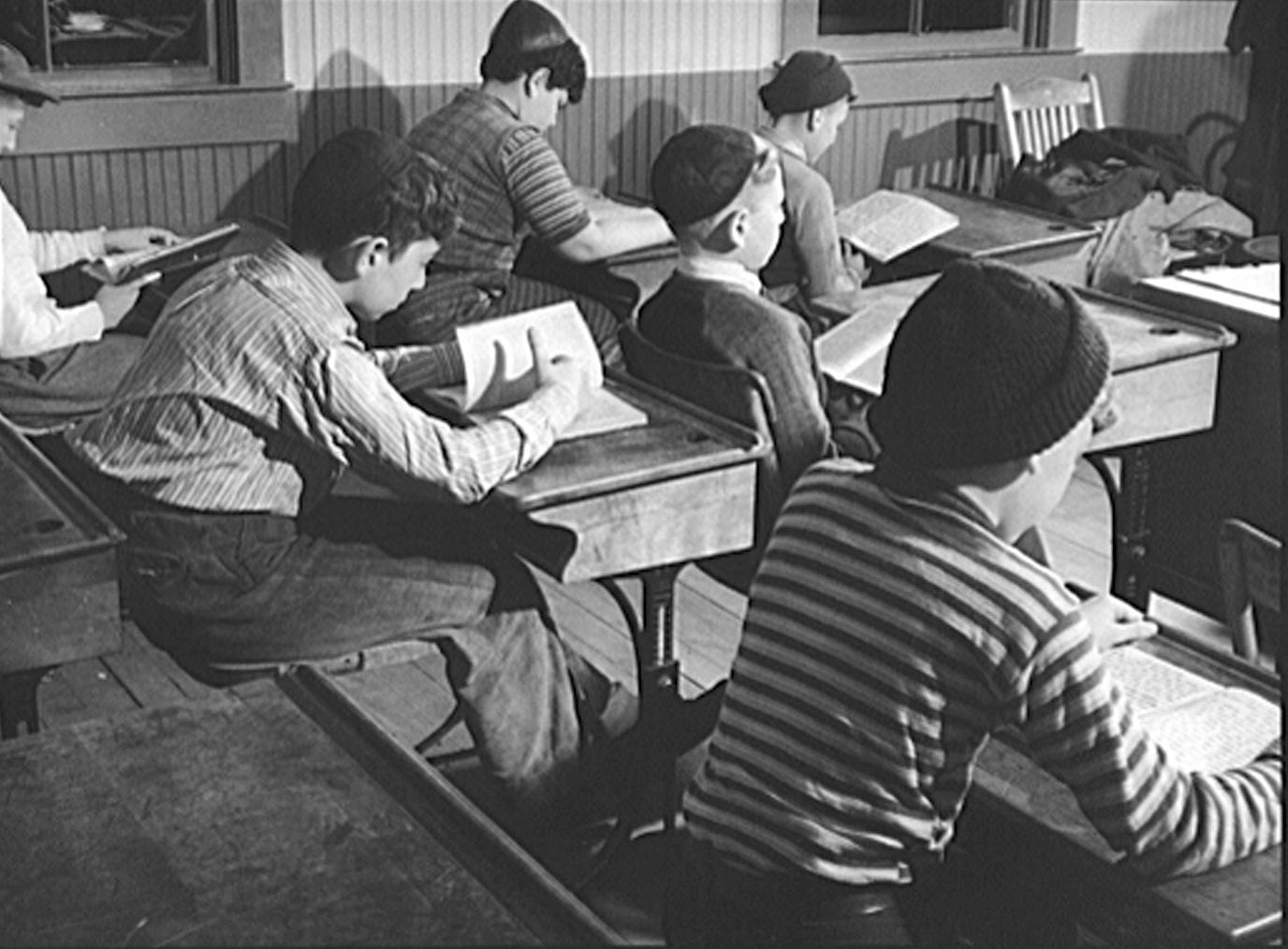

In primary school terms, formal Jewish education in the United States typically takes two forms: part-time education (more colloquially known as “Hebrew school”) and full-time education (better known as “Jewish day schools”).

Part-time Jewish education (“Hebrew school”) was started as an answer to the traditional Christian Sunday school. Rebecca Graetz of Philadelphia, a devout Jew and philanthropist who wanted Jewish children raised in non-Orthodox homes to have a grounding in Jewish history and traditions, is credited with cultivating the concept.

In 1818, on her birthday, the first Hebrew school was opened by the Female Benevolent Hebrew Society of Philadelphia with 60 students. The problem is that “this system, created 200 years ago, has remained largely structurally untouched since,” according to Rachel Lithgow, a longtime Jewish nonprofit executive.2

As a product of part-time Jewish education at a synagogue in Los Angeles, I can personally attest to its ineffectiveness in building and expanding a formidable Jewish identity centered around Israel as our Jewish capital, instilling profound knowledge of all 4,000-some-odd years of Jewish history, and helping children develop the know-how to find a healthy balance between their Jewish and non-Jewish lives.

Then there is full-time Jewish education (“Jewish day schools”), which is often seen, especially by those who work in and fund it, as a remarkably more effective alternative to part-time Jewish education. What these folks prefer to less frequently talk about is how most Jewish days schools have become capitalist-infested, in many cases much more expensive than tuition at great universities. Again, we’re talking about primary schooling, not higher education.

Those in favor of Jewish day schools claim that their tuition fees are a reflection of hiring quality teachers and delivering quality instruction in quality facilities. That might have been true before the advent of the internet, but today these claims are a lame excuse that distorts the actual reality: a lack of innovation to deliver quality Jewish education to the most amount of people, in the most inexpensive (i.e. accessible) ways.

In other words, Jewish day schools and their ridiculous costs to parents have made them increasingly inaccessible and unattractive to the average Jewish parent. And it’s Jewish day schools that seem to be the only sector in which organizations are exponentially serving less and less people, while continuing to spend more and more money on human resources and facilities.

The result? Exponentially more Jewish kids are growing up with a significant lack of knowledge about Judaism, Jewishness, and Israel — plus the Jewish identity that comes with this knowledge. When our kids aren’t properly and effectively educated from a young age, they grow up yearning to assimilate in non-Jewish ways.

Just look at Reform Judaism, now the largest of streams in the United States. It has embraced popular liberal trends like social action, care for the environment, and the welcoming of members of LGBTQ and interfaith families — which are all good and well — but I’m not sure how much longer the movement can sustain itself by championing autonomy without requiring any imperatives.

Jack Wertheimer, a professor of American Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary, believes “the problem is when assumptions are made that Judaism and non-Jewish cultures are part of one seamless fabric and that there are no tensions between the two.” He sees Judaism as “countercultural in some ways,” and that if we don’t emphasize the differences, “the essence of Jewish life will be distorted or lost.”3

I would argue, Jewish distortion and loss are very much staring in the eyes. Just look at how many Jews either don’t want to or don’t know how to say anything Jewish about the current Israel-Hamas war. From my viewpoint, this can be attributed to:

Fearing adverse or inconvenient reactions from their non-Jewish social circles and workplaces

Not having a strong Jewish identity (i.e. one tied to Israel) and, with it, the courage to speak up

Being over-assimilated and not realizing that the current spike in antisemitism across America has little to do with the Israel-Hamas war, and much more to do with the fact that antisemitism was always hiding there; this war was just a convenient opportunity to unleash it yet again

3. Growing Arrogance and Ignorance

The arrogance of many American Jews is that they think they’ve finally found a safe and welcoming place in the United States.

Their ignorance? They either forgot or never knew that this is the exact same mindset, primarily among German Jews, which led to six million Jews being annihilated in the Holocaust.

But don’t take this threat from me. All you have to do is read about the large swaths of German Jews who were so comfortable in German society and thought that their non-Jewish German friends and colleagues would never turn on them — and then did (or stayed quiet as other Germans turned on them). How’s that going for those German Jews right about now?

A Holocaust will come to America, just not in the form of Nazis going door-to-door to round up the Jews. An American Holocaust will look more like Jews feeling increasingly unsafe about being and doing Jewish outside of the confines of their home, that they’ll stop sending their kids to part-time or full-time Jewish schools; they’ll stop visiting Jewish places of worship; they’ll stop buying Jewish foods at the market; they’ll stop taking trips to Israel; and they’ll stop raising their kids Jewish.

Eventually, Jews that remain in America will either live in Orthodox communities, only do Jewish activities in their homes, or renounce their Jewishness altogether because it will have become such an emotional and psychological burden to be and do Jewish. In other words, death by assimilation.

In the meantime, American Jews, many with deep pockets, will continue to think that they can buy support, but the Arabs (with a diametrically opposed agenda to us Jews) have way deeper pockets.

According to a study published in 2022 by the National Association of Academics in the United States, a study that did not attract much attention at the time, the Qataris donated $4.7 billion to U.S. universities starting in 2001, precisely after the September 11th attacks. (The recipients, however, did not report part of the money received, as required by law.)

In another report comprising four separate studies, at least 200 American colleges and universities illegally withheld information on approximately $13 billion in undisclosed contributions from foreign regimes, many of which are authoritarian.

As Arabs continue to up the ante with their donating and lobbying, Jewish donors and lobbyists in America will become exponentially less relevant.

Plus, with the birth of Western Islamism, Islamists and their “woke” friends have been mindful of staying away from blatant antisemitism because of post-Holocaust “guilt” in the West. Hence why they’ve altered their strategy into a much more socially acceptable one called “anti-Israel” — just as the Soviets once did too. And, frankly, it’s been working like a charm, so much so that many American Jews have joined this movement.

4. Jewish Disunification

There’s only one place in the world where it’s mainstream to be an ultra-Orthodox Jew, a modern Orthodox Jew, a conservative Jew, a reform Jew, a Reconstructionist Jew, and Jew-ish. You guessed it, it’s the United States of “Be Whatever Kind of Jew Your Heart Desires.”

Spanning decades of exaggerated liberalism seeping into U.S. Jewish communities, many Jews in America have become highly judgmental, cynical, and even hateful toward one another, leading to what we can call “Jewish disunification.”

Whereas many American Jews think that the key to American Jewry’s success lies in alliances with non-Jews and non-Jewish organizations, I believe the key to American Jewry’s success lies in the unification of American Jews, of American Jews with Israel, and of American Jews with other groups of Jews in the Diaspora.

A victory for Hamas, and by extension, Iran, will not be the reopening of the scourge of antisemitism in America. After all, antisemites don’t need Hamas and Iran to live their best antisemitic lives. A victory for Hamas and Iran will be the increasing disunification and fracturing of American Jewry, as well as the staggering disconnection between American Jewry and Israel.

5. Jewish Leadership (or Lack Thereof)

Now that people are parading in the streets and cheering on Jewish genocide, it’s easy for so-called Jewish leaders to wave the largest Israeli flag they can find and vow to take “immediate and concrete action” (whatever that is).

But look around at the disarray, the chaos, and the betrayal of Jews by alleged friends and allies, and you’ll see a colder truth: Jewish leadership has gone bad. Or maybe it was never that good to begin with.

Bad Jewish leadership has “failed us on college campuses, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into ‘advocacy’ while sucking up to university administrations and leaders turning once-illustrious institutions into festering swamps of antisemitism,” Alana Newhouse, the founder of Tablet magazine, aptly wrote.4

She added that bad Jewish leadership has failed us on the international scene, complicit in the single greatest blow America has ever dealt to Israeli security, the Obama administration’s Iran deal, “while mumbling stupidly about bipartisanship.”

“They swaggered about D.C. declaiming their political clout and influence, yet they were unwilling, when the hour of need arose, to withdraw their support for those intent on giving a genocidal, Holocaust-denying regime hundreds of billions of dollars, regional legitimacy, and the power and motivation to resume exporting death and destruction against its enemies, the Jews first and foremost,” Newhouse wrote.

Bad Jewish leadership has failed us on the political front, “rushing to embrace obvious Jew-haters,” according to Newhouse. She gave the example of New York’s Jewish Community Relations Council, which was eager to engage progressive U.S. politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in a “fawning dialogue” while simultaneously hosting seminars on “white supremacy” and cracking down on Orthodox communities that dared to defy the state’s draconian COVID restrictions.

Bad Jewish leadership has failed us by failing to prioritize our own, very real needs, abandoning its core mission — to serve and protect Jews — “in order to imagine itself instead as yet another tile in the mosaic of the Democratic Party’s contemporary coalition of grievances,” Newhouse wrote.

Earlier this year, when a Tablet staffer asked a senior executive at a very large American Jewish organization what their group’s top priority was for the year, this person replied, without missing a beat: “Ukraine.” I get it, Ukraine needs and deserves help, but if your priorities are such that serving and protecting Jews takes a backseat to issues that have nothing to do with your constituents, I’m not sure that you are in the right line of business.

“In every precinct and every channel, these leaders not only failed to see what was coming down the pike; they also did their best to sideline and even demonize those who did,” Newhouse wrote.

I can’t tell you how many so-called leaders at U.S. Jewish organizations I’ve personally engaged — including Andres Spokoiny of the Jewish Funders Network, Adam Lehman of Hillel International, and Russell Robinson of Jewish National Fund — who say all the right things, yet are largely stuck in outdated operating models, buzzwords, groupthink, bureaucracy, territorialism, and vanity metrics.

American Jewish nonprofits have become cesspools of capitalism (i.e. obsessively fundraising on the back of every issue, big and small, directly or indirectly, that Jews face). They are, in many ways, everything that is bad about America. With the exception of social services work and funneling billions of dollars to Israel, they have failed American Jews, all in all.

Many of them have even deepened the divide between American Jews and Israel. A few weeks ago, on multiple calls with Jewish communal professionals, some argued: “We need to hold space in the Jewish community for Jews who are struggling in this moment because they don’t support Israel.”5

Do we? Or do you, like me, agree with Newhouse who said: “It seems to me this is an opportunity to bring clarity to what has been obscured, by answering charges like this one as directly as possible: ‘It is very important that we not misrepresent ourselves, because then these people will ultimately — rightly — feel gaslit. We are Zionists, and we believe that Zionism is central to our work. If this makes our spaces not right for certain people, we need — for their sakes and ours — for them to know it now.”

For the last few years, I’ve been calling for a new era of Jewish organizations: ones with courage and clarity, Israel at its epicenter, disruptively innovative models and strategies, and young up-and-coming leadership. I would add that it’s this new era of organizations which can partner with the incumbents, but then again, what got us into this mess won’t get us out of it.

6. How American Jews Are Raised

The idea of “holding space” is a social epidemic in greater America and across other parts of the world. By putting their kids in safe zones and creating an “everyone gets a trophy” culture (which makes kids feel extra special), American Jews, like their peers, have largely raised kids to think they are untouchable.

When you think you are untouchable and extra special, you think you have no enemies, or you presume your enemies could never in a million years reach you. Just like many Americans thought their homeland was unreachable by its enemies — until 9/11.

In these environments of “safetyism,” children are handicapped with the prevention of developing resiliency. Experts believe this plays a factor in adult-age disputes, since young adults become acculturated to avoiding anything that may seem challenging or burdensome.

By over-indexing on illusions, myths, and “perfect world” thinking, kids aren’t educated about the harsh and harmful realities of life, such as those related to war and military conflicts, socioeconomics, immigration, politics, history, other societies which promote varying political systems and values, and a plethora of other issues.

I call these Jews “fragile Jews” because they do not have the psychological and emotional capabilities to deal with anything that doesn’t fit perfectly into their narrow-minded worldviews, beliefs, and intellect.

With an overemphasis on Holocaust education — not to be confused with a vital emphasis on the Holocaust, just not an overemphasis — “fragile Jews” display an old Jewish pattern of relying on powerful non-Jewish guardians, whose ongoing protection had to be secured through techniques such as politics, business, and socioeconomics.

Their favorite Jewish books are not “Man’s Search for Meaning” or “In the Land of Israel.” They are books about dead Jews — such as “Maus,” “Anne Frank: Diary of a Young Girl,” and “Night” by Elie Wiesel.

Had Israel lost its War of Independence in 1948, we would have produced a thousand more books about dead Jews, and American Jews would be the first in line to buy them. Instead, the nuisances that Israelis are, they won this war, the price for which was “occupying” land in fear that it would otherwise be a launching pad for Arabs to continue attacking Israel, with the goal of ridding Jews from the Middle East.

“That a muscular Jew was an unwelcome prospect to Arab nations, accustomed to seeing him as a semi-castrated pushover who poisoned their wells, was only to be expected,” Howard Jacobson, a famed British journalist and author, wrote. “More surprising and problematic is that there are Jews who have difficulty with this new reality too.”6

7. A Fraught Relationship With Israel and Zionism

Young American Jews are less emotionally attached to Israel than older ones. As of 2020, less than half of Jewish adults under age 30 described themselves as very or somewhat emotionally attached to Israel, compared with two-thirds of Jews ages 65 and older.7 And one-quarter said it’s not important to what being Jewish means to them.

In another survey of American Jews, taken after the 2021 Israel-Gaza conflict, a quarter of them thought that Israel is an “apartheid state” and 22-percent believe “Israel is committing genocide.” Hence why, according to another poll, 95-percent of Israeli Jews feel that they have a moral obligation to Jews of the Diaspora, but only 57-percent believe the relationship is in a good place.

Even as more American Jews continue to isolate themselves from Israel and Zionism, the problem is not that Israel will give up on American Jews. Instead, the problem is that United States will give up on them, for it already has.

U.S. college campuses are becoming uncomfortable and unsafe for Jewish and Israeli students, and more and more Jewish places of gathering are becoming targets for hate crimes. I’m not just talking about synagogues and Jewish schools, but also Jewish delicatessens and old-age homes.

I have no doubt that U.S. police and the FBI will do their best to protect Jews and Jewish communities, but all we have to do is look at the situation in England to realize where things are headed in America: Law enforcement will be increasingly overwhelmed by threats of anti-Jewish crime, meaning more of these threats will go undetected or under-policed, which will increase the likelihood that Jew haters will “successfully” carry them out.

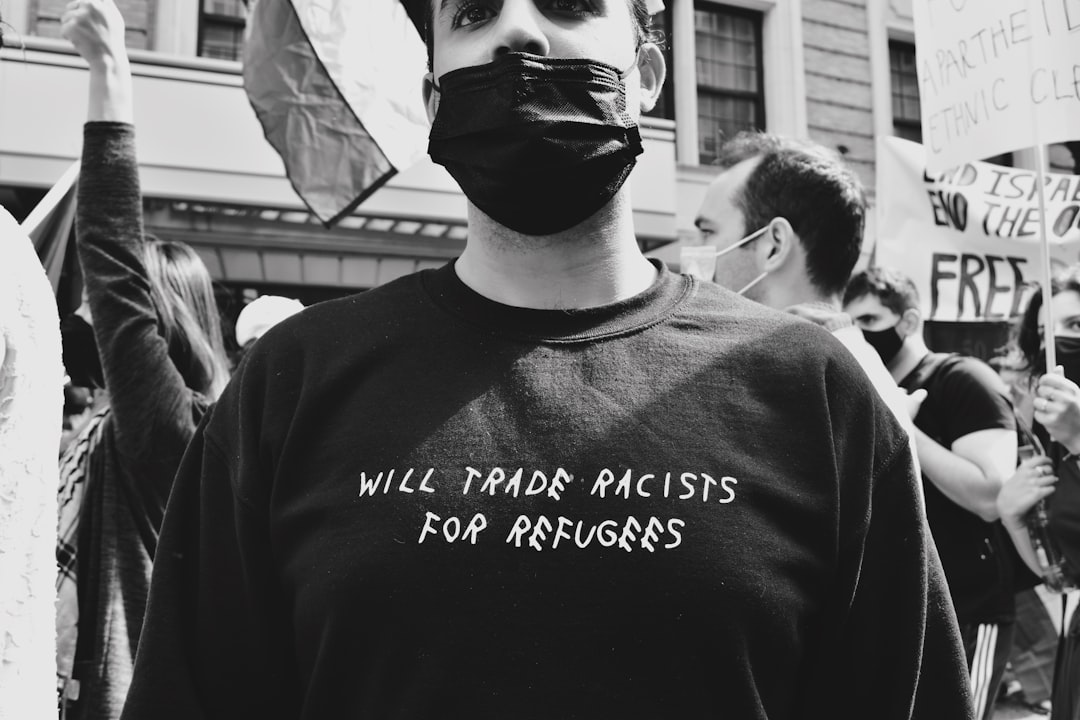

8. The Rise of Progressive Liberalism Among American Jews

For the past century, American Jews have consistently leaned to the left of most other Americans. Exceptions, like Orthodox Jews or recent immigrants, are dwarfed in size and influence by the majority of American Jews who identify as liberal and whose politics have shaped both the modern Democratic Party and the national political culture.

A Pew study from 2020 found that seven-in-ten American Jewish adults identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party, and half describe their political views as liberal.

And the only estimate of American Jewish progressives comes from a recent national survey sponsored by Keren Keshet, which found that about eight-percent of American Jews identify as progressive, 14-percent identify as very liberal, and another 25-percent as liberal. In all, 47-percent of American Jews are in the left camp (liberals and progressives).

However, the Keren Keshet survey illustrates numerous differences between liberals and progressives. When asked about how much they worry about various specific political issues, compared to liberals, Jewish progressives express more concern about climate change and racism, but far less concern about crime (probably because many Jewish progressives grew up in overly sheltered environments where crime was but a word).

These findings continue a long-standing trend of progressives being far more ideologically extreme, “woke,” and intolerant of difference compared to liberals. Across the United States, progressives are far more likely to want to silence dissent and censor open exchange, are notably more politically active than their liberal and conservative counterparts, and are far more likely to live in echo chambers where their views and voices are increasingly radicalized and divergent from the political center.

Though progressive Jews often try to connect their political stances to beliefs in Jewish religious or cultural tradition, progressives were the most anti-religious group in Keren Keshet’s survey results. The majority of Jewish progressives have no Jewish denominational identity, compared with 43-percent among liberals. The aversion to denominational identity even extends to Reform Jewish identity.

For both liberals and progressives, of the denominational choices — aside from “no denomination” — Reform is the most favored denominational choice. But, that said, it is substantially more popular among liberals than among progressives.

The progressives’ detachment from religion in general and conventional Judaism in particular is reflected in their marital patterns. Since people tend to become more religiously engaged with marriage and even more so with parenthood, it is no surprise that almost half of Jewish progressives are single.

“Today the preeminence of this Jewish-liberal alliance is threatened not from the right, but by the rising power and increasing population of Jewish progressives,” according to Samuel Abrams, a professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College. “While their numbers are still small relative to the overall community, left-wing progressive Jews are organized, vocal, engaged, and disproportionately influential on the national political scene.”8

“These progressive Jews are appreciably less engaged in Jewish life and with historic Jewish institutions than their more moderate liberal and centrist counterparts,” Abrams added. “Additionally, they lack the traditional pro-Israel sentiments that have been a hallmark of the Jewish American community for decades. As such, this growing bloc of progressive Jews may fundamentally alter the political priorities and preferences of the Jewish community going forward, with radically new views about social justice and Israel and notably anti-institutional and anti-religious inclinations.”

Abrams argues that, since 2018, several new or growing Jewish communal groups are correlated with the rise of Jewish progressives. Repair the World, Truah, Jewish Voice for Peace, Bend the Arc, and If Not Now have all benefited, despite their many ideological and stylistic differences, from a surge in Jewish ideological engagement on the left.

“For religious traditionalists and cultural conservatives,” he wrote, “this is a self-evidently disturbing phenomenon. Jewish progressives are seen as placing undue emphasis upon the tikkun olam — social justice — dimension of Jewish life, while downplaying other valued aspects of Jewish tradition. They may also be seen as unduly critical of Israel to the point of undermining the political legitimacy of the Jewish state.”

The confusion about the meaning and implications of Jewish progressivism are derived, in part, from conceptual ambiguity among progressives themselves. Like many well-established political terms, progressivism has changed its meaning over time, “used sloppily without precision or a set of coherent beliefs and policy preferences,” Abrams wrote.

Hence why you’ll hear these progressives say things like, “I’m not really Jewish, just Jew-ish” despite doing virtually nothing in the way of being Jewish. And when you encourage them to take part in more conventional Jewish practices or customs, they say things like: “That’s too Jewy for me.” — echoing Jews like Sigmund Freud, who said in a famous television interview in 1918:

“Although my family were Jewish and I am genetically Jewish. I have absolutely no subscription to the creed and no interest in the race. I don’t believe in race and I find racial notions so objectionable that I can’t think of myself as being Jewish in that way.”

To this end, the Keren Keshet survey showed that progressive Jews are the least likely to frequent a Passover Seder, belong to a synagogue, attend services monthly, feel that their children should be active as Jews, visit Israel, and feel at least somewhat emotionally attached to Israel. When asked if the U.S. is too supportive of Israel, 42-percent of Jewish progressives agreed, compared to some 10-percent of Jews that identify with other political groups.

“With increasing numbers of American Jews assuming the progressive label, and with developments in Israel proceeding as they have been recently, the difficulties of navigating the politics of Jews and Jewish life will only intensify,” Abrams wrote. “For progressives, Israel is on the wrong side of the narrative and even of history, becoming a key test of ideological purity and commitment. Being highly critical if not overtly hostile toward Israel is not simply one stance among others for Jewish progressives: It is a defining feature of their political identity.”

But what these progressive Jews don’t realize is that our enemies don’t care how liberal or conservative, American or Israel, pro-Israel or anti-Israel, God-fearing or secular you are. In this vein, I’ll defer to a post I recently saw on Instagram, which said:

When they came for the Republican Jews, I said, “I’m not a Republican!”

When they came for the religious Jews, I said, “I’m not religious!”

When they came for the Israeli Jews, I said, “I’m not Israeli!”

When they came for the Zionist Jews, I said, “I’m not a Zionist!”

When they came for the Jewish Democrats, I said, “I’m not really a Democrat!”

When they came for the progressive Jews, I asked, “Why? I stayed in every lane you told me to.”

“Thank you,” they said. “But you’re still a Jew.”

Even then, what might be most ironic about these Jewish progressives is that victim-blaming appears to be a crime to so many of them. Except, well, when it comes to Jewish victims. Israelis, do I mean? Those of us more educated and enlightened know this antisemitic ploy all too well, the attempt to make a distinction between Israeli and non-Israeli Jews.

To be sure: Jews can be antisemitic, and many progressive Jews are. The progression starts from self-criticism to self-suspicion, self-hatred, self-disgust. Call it self-blame and no one minds too much. “My punishment is more than I can bear,” said Cain when he bore it, and self-scrutiny got us in and out of Babylon in reasonably good shape. (Not that progressive Jews would know Jewish history, though.)

But what, if it is not self-hate and self-disgust, are we to call the condition dramatized in “Farewell Leicester Square” — a novel written in 1935 by a Jew, about Jews making one another skin creep, a good few years before what some call “the Israeli occupation,” but already not a good time for Jewish writers to be careless with their words.

“Just admit it, you Jews who must tell the world that Jews have no business in a country that they should have put behind them actually and imaginatively centuries ago,” Howard Jacobson, a famed British journalist and author, wrote. “Just admit that, however lucid you think your analysis, you are as compromised by your longing for a Jew-free future as the theology crazed settlers you despise are for a Jew dense past.”

To root for the Palestinians or any other non-Jewish peoples is not self-hate, if you think you’re rooting for the “underdog.” But this so-called underdog is not indigenous to Israel, and they very much colonized the land, just so all the decolonization-obsessed progressives are aware.

Plus, a recent poll by an esteemed Palestinian pollster found that more than 70-percent of Palestinians support armed resistance (i.e. terrorism) against Israelis, and feel that Hamas is not engaging in enough terrorism against the Jewish state. So let’s be clear about who these progressives are rooting for: terrorists and terrorist-sympathizers.

Notwithstanding, it’s clear that American Jewish progressives continue to exert an outsize influence over the United States’ mainstream political establishments. Moreover, “there is little question that the relative influence and numbers of Jews in powerful roles, from cultural institutions, to higher education and public affairs, are in steep decline,” according to Abrams, “and Jewish progressives today are leading the entire Jewish community down that path.”

“This is not an inevitability, and the relative numbers here are small,” he continued, “so the rest of the Jewish community — liberals, moderates, and conservatives — must engage now if they do not wish to see their collective power eroded further. This is a textbook example of tyranny of the minority, and like mainstream American politics being dominated by the extremes rather than the large and moderate center. If that center can reassert itself remains an open question.”

“The Takeover.” Tablet. https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/the-takeover.

“Reimagining the Jewish education model.” eJewish Philanthropy. https://ejewishphilanthropy.com/reimagining-the-jewish-education-model.

Rosenblatt, Gary. “U.S. Judaism Today, Striving To Stay Relevant.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency. September 20, 2018, https://www.jta.org/2018/09/20/ny/u-s-judaism-today-striving-to-stay-relevant.

“Replace American Jewish Communal Leadership.” Tablet. https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/replace-american-jewish-communal-leadership-adl.

“Replace American Jewish Communal Leadership.” Tablet. https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/replace-american-jewish-communal-leadership-adl.

“‘Antisemitism is the passion dead Jews arouse in their killers to kill more of them.’” UK Jewish News. https://www.jewishnews.co.uk/howard-jacobson-im-glad-my-mother-and-father-arent-alive-to-hear-what-the-jew-haters-accuse-us-of-now.

“Jewish Americans in 2020.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/05/11/jewish-americans-in-2020.

“The Takeover.” Tablet. https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/the-takeover.

Hi Joshua, my life story began in almost reverse to yours; born and raised in Tel Aviv until I was 13 years old, then to L.A., then to Las Vegas where I've built my life (yes, Vegas). Being an Israeli Jew in America, particularly at the start, was a stark reminder of our inherent strangeness in the world. You aren't wrong about anything you wrote, and if I'm not mistaken, there was a rebuke in your words, or maybe you weren't trying to hide it at all, I'm not sure, I sort of devoured the article. But either way, I agree with it all. I would only add, or simply emphasize, that it has been my experience that that self-hatred is so deep that IT is what has led American Jews to the Left and to assimilation that purposely seeks to shake off the 'stink' of their Jewishness, including a seething anti-Zionism, so that they will be seen as 'regular' people rather than be distinguished by the beauty of who we are, ushered in no small measure by the transgenerational trauma to which you've so astutely pointed- it's very real. I guess what I'm trying to say is that, after reading this piece and being reminded of its hard truths, I am almost completely heartbroken in this post October 7th world. I still can't believe that something so horrific happened to my people in my birthplace that despite all its plain shortcomings, ever made me feel unsafe but rather normal, modern- and above all, protected. These proud shows of antisemitism have now shattered everything I've held onto and, most sadly, pushed me to seek solace on Instagram, which I hate. Though it offers some palliation. But I wonder, was it simply an allusion I was holding on to? Were we Jews always so fragile and will we ever recover? Will Israel endure? How is this our reality now. In my grief and fear though, I feel so emboldened that even if all the answers to the latter won't offer comfort, I'm too pissed off to give up or allow anyone to make me feel like a weak Jew. I can't and I won't. I look at Israelis, my family too, and I feel so bad it brings tears to my eyes and an ache in my very being for them because they just want to live. They so always want to show the world that they are normal, modern and good, but i never works. And despite being taught that all the world will always hate us for being Jews, I will never understand that hatred.

At any rate, your articles have been giving me so much food for thought, pride and strength because I believe that your defiance is coming through in them and it's inspiring and invigorating. Please don't ever stop writing them.

So if I'm reading the tea leaves correctly, Hamas has done its job. Not only is antisemitism at an all time high here in the United States and around the world, but now Jews are on the road to self- destruction. I hope not...