Jewish sources say a lot about conquering Gaza City.

I'm not overly religious, so I wanted to know what our ancient sources say about Israel's pending conquest of Gaza City. The answers may surprise you.

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

Israel stands at another pivotal moment.

After nearly two years of bitter fighting, harrowing hostage dramas, and another stalled partial deal with Hamas, the government has decided to move forward with conquering Gaza City — the heart of Hamas’ power and one of the most fortified urban battlegrounds in the world. The IDF chief has vowed to carry out this mission “in the best possible way,” and the security cabinet has given its formal approval.

To the outside world, this may appear as a purely military operation — another battle in a long, bloody conflict. But for the Jewish People, this moment is layered with meaning. Gaza City is not just a dot on a map; it is a place with deep historical resonance. It was once a Philistine stronghold that launched raids into ancient Israel, and it has, across millennia, been a base for forces seeking to weaken or destroy the Jewish presence in the Land.

The names have changed — Philistines, Egyptians, Ottomans, British, Hamas — but the pattern is painfully familiar: a hostile power entrenched in Gaza, using it as a spearhead against Jewish life.

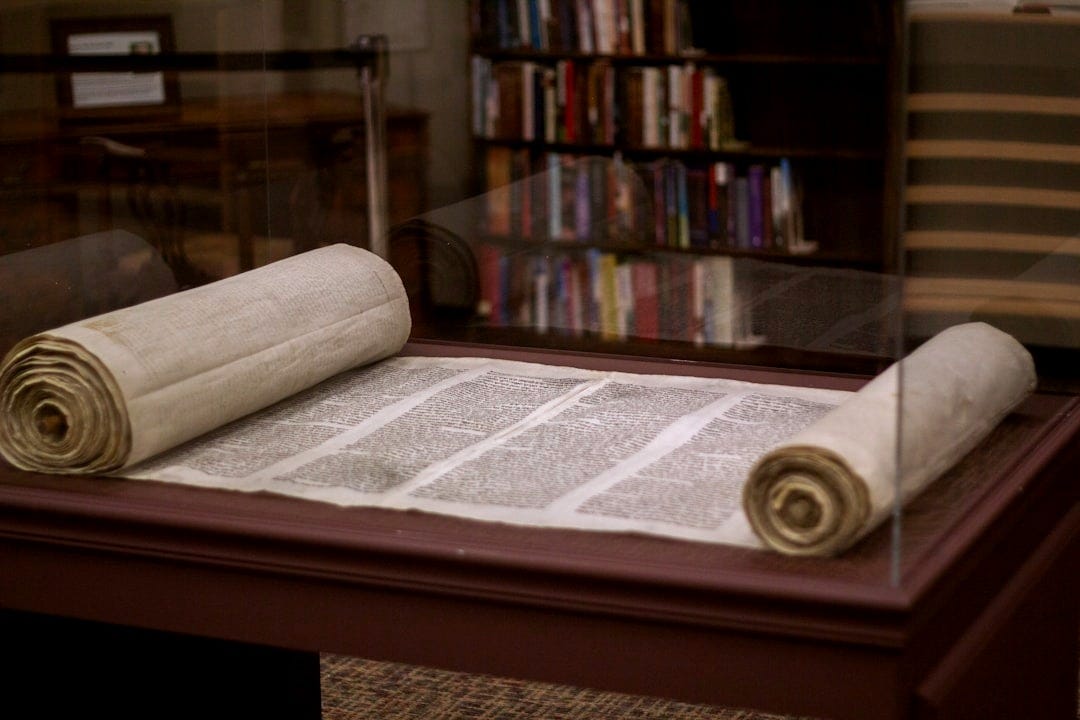

Jewish tradition has never glorified war. The Torah, the Talmud, and centuries of rabbinic commentary view armed conflict as a grim necessity, not a noble pursuit. Yet they also recognize that there are times when a nation must take decisive, even forceful action to protect itself. In the language of halacha, this is the difference between a war of choice and a war of obligation. When an enemy threatens your people’s existence, you are not merely allowed to respond; you are commanded to.

More specifically, the Torah recognizes that war is sometimes necessary, but never desirable. In the Book of Deuteronomy, we find laws distinguishing between a milchemet mitzvah (obligatory war) and a milchemet reshut (permissible war). Maimonides explained that a milchemet mitzvah includes wars of self-defense against enemies who threaten Jewish lives.

By any reasonable halachic measure, the battle for Gaza City — against an armed faction sworn to Israel’s destruction, which has already carried out massacres and kidnappings — is a milchemet mitzvah. The Torah commands, “Do not stand idly by the blood of your fellow.”1 Allowing Hamas to regroup, rearm, and plan future attacks would be the very definition of standing idly by.

Meanwhile, the Talmud articulates the principle of rodef: If someone pursues another with intent to kill, one is permitted, even obligated, to stop the pursuer by any means necessary. Hamas, by both ideology and action, functions as a rodef against Israel. As such, halacha would see neutralizing its power base in Gaza City not as an act of conquest for conquest’s sake, but as fulfilling a mitzvah to save life (pikuach nefesh).

This is not unique to our era. The Book of Judges recounts repeated cycles in which Israel’s survival depended on dismantling nearby hostile powers. King David’s campaigns against the Philistines were not imperial expansion; they were existential necessity.

Here, history offers an even sharper parallel. Gaza appears multiple times in the Hebrew Bible as a Philistine stronghold, a recurring launchpad for attacks on Israel. The Midrash depicts the Philistines as those who “blocked the wells,” cutting off life and sustenance — an image hauntingly mirrored by Hamas’ use of tunnels, human shields, and blockades to choke Israeli security and threaten civilian life. The Jewish memory of Gaza as a persistent source of danger is as old as our people’s presence in the Land.

What’s more, Jewish law does not require passivity until an attack is underway. The Talmudic maxim, “If someone comes to kill you, rise early to kill him,” applies not only to individual self-defense but to national security. The Shulchan Aruch explicitly rules that, even on Shabbat, one must mobilize if an enemy is approaching — even before they strike — to prevent danger.

From this perspective, taking Gaza City now is not an act of escalation, but of prevention. It is removing the capability of an entrenched enemy to repeat October 7th on a larger scale.

On top of that, the Torah commands, “Remember what Amalek did to you… do not forget.” Amalek was not merely a geopolitical rival; it was a people defined by implacable hatred, attacking the weak and innocent. Halachic tradition understands that some enemies are driven by such absolute hostility that they cannot be placated or ignored.

While Hamas is not Amalek in the literal genealogical sense, its charter, rhetoric, and actions align with that same ideology of annihilation. The mitzvah to remember Amalek is, at its core, a warning: Do not grow naïve about the nature of certain threats, and do not leave them in place to strike again.

Then there’s this: Jewish sources recognize that war is fought not only with swords and shields, but in the reshut harabim — the public domain. How we conduct ourselves shapes not just military outcomes but the moral narrative told to the world. The Torah’s call to be a “wise and understanding people” is, in part, a call to wage war with integrity.

We should also remember that the Hebrew Bible warns repeatedly about the perils of incomplete action. In the Book of Judges, Israel’s failure to fully remove hostile powers from the Land led to generations of renewed attacks and spiritual compromise. Leaving even a remnant of Hamas’ military and governing infrastructure intact risks repeating this cycle. Jewish history and halacha both counsel that, when faced with an existential threat, half-measures invite its return.

While Judaism permits war for defense, it imposes strict limitations on conduct. Devarim forbids wanton destruction of resources, the famous bal tashchit (do not destroy) principle. The Ramban extended this to prohibit harming civilians or infrastructure unnecessarily.

The Talmud tells of Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai ordering his soldiers not to cut down fruit trees during a siege, underscoring that even in times of war, the sanctity of life and creation remains. This ethic echoes through the IDF’s own doctrine, which, despite inevitable failures in practice, is built on tohar haneshek — purity of arms.

At the same time, halacha recognizes the tragic reality that, when an enemy hides among civilians, the moral responsibility for collateral harm lies with the aggressor. Rabbi Shaul Yisraeli wrote that, if non-combatants suffer because they are used as shields for military targets, the guilt is on those who placed them in harm’s way — not on those forced to stop the threat.

Jewish tradition also warns that winning a battle is not the same as winning peace. The Torah repeatedly commands, “When you come into the land…” followed by instructions to establish justice, care for the stranger, and avoid arrogance in power. Conquest without moral governance is hollow and dangerous.

The Sifrei on Devarim notes that a Jewish army is most secure not through numbers or weapons, but through righteousness and moral clarity. After Gaza City is taken, the moral test will be how Israel governs, ensuring security for its citizens while preventing oppression of civilians, and creating conditions where war cannot reemerge.

In Jewish thought, the conduct of war is also a stage for Kiddush Hashem (sanctifying God’s name) or, God forbid, Chilul Hashem (desecrating it). The prophet Ezekiel warned that the desecration of God’s name comes not only from weakness but also from injustice in power. How Israel acts in Gaza City, even under immense provocation, will shape how Jews are perceived worldwide. This responsibility is both strategic and spiritual.

In addition, the prophets of Israel consistently remind us that war is not the Jewish ideal. Isaiah envisions a time when “nation shall not lift up sword against nation.” Even King David, though victorious in battle, was told by God that he could not build the Temple because “you have shed much blood.” The implication is clear: defense is necessary, but peace remains the ultimate aspiration.

In this light, conquering Gaza City is not an end, but a step toward a broader vision — one in which Jewish strength serves as a foundation for safety, stability, and eventual reconciliation when circumstances allow. The original rabbinic concept of tikkun olam — ordering the world so harm cannot flourish — applies here: The true victory will be a just post-war order that prevents the return of war.

And this week’s Torah portion, Parshat Va’etchanan, speaks with striking relevance to the current moment. Moses yearns to enter the Land but is told he will only see it from afar, a reminder that the Land of Israel is not simply a piece of real estate, but a sacred trust, bound to God’s covenant with the Jewish People.

The portion commands Israel to remove existential threats from its midst, not out of vengeance but to preserve the nation’s spiritual and physical survival. It warns us never to forget the dangers we have faced. Conquering Gaza City, then, is not about expanding borders or flexing power; it is about fulfilling the mitzvah to protect life, uphold justice, and secure the covenantal inheritance entrusted to our care.

Finally, there is the urgent, agonizing question of the remaining Israeli hostages whom Hamas has visibly starved and brutalized. Jewish history teaches that such dilemmas are tragically familiar.

The mitzvah of pidyon shvuyim — redeeming captives — is among the highest in our tradition, yet there have been moments in our story, from pogroms to modern battlefields, when unbearable choices had to be made. From Masada to Entebbe, our people have chosen survival over sentiment — not from cruelty, but from the clear-eyed conviction that without survival, there is no future to redeem.

And that is what this moment demands. To conquer Gaza City is not to turn our backs on the hostages, but to ensure that no more Jews are taken, no more families are shattered, no more enemies are emboldened by our restraint. It is to choose life — for this generation and the next.

Our tradition does not shy away from hard truths. It teaches us to act with strength and conscience, to fight when we must, and to build a peace worthy of the sacrifices we make. The choice before us is not between war and compassion; it is between hesitation that brings exponentially more risks, and action that secures a Jewish future.

Leviticus 19:16

So well informed, interesting and useful. Josh, you must become a rabbi and we, your readers, will quickly join your congregation. Thank you always for your insights and for your encouragement! 🙏🏻⭐🙏🏻⭐🙏🏻⭐

Your explanation is pure and truth! I say Israel has a God given right and responsibility to take back what God gave the “Children of Israel” thousands of years ago through His Devine Land Grant! And to rid Israel of the still alive Philistines to this very day! My prayers for today’s ISRAELI WARRIORS IS THAT GOD WILL GIVE THEM HIS WISDOM, VISION, STRENGTH AND DISCERNMENT TO SEE!

Shalom🙏