The Strange Psychology of Self-Hating Jews

Did you know that Jews can be antisemitic?

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free and zero-advertising for all.

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

Did you know that Jews can be antisemitic?

Yes, you read that correctly. Jews can be antisemitic, self-hating. Trust me, there are crazier things in this world.

In 2020, when two ultra-famous Jewish comedians, Marc Maron and Seth Rogen, had a go at American and Israeli Jews on Maron’s popular podcast, many listeners were shocked at how ignorant and tone-deaf they both sounded.

Maron and Rogen might have been joking about topics related to Jewish people and Israel, but their perspectives are warped by a failed educational system, which taught them to generalize a whole population based on their individual experiences, while amplifying antisemitic and Jew-hating tropes to their massive audiences.

Yet, Jew-on-Jew antagonism is not a new phenomenon. Tiberius Julius Alexander was a Jewish governor and general in the Roman empire who ordered 5,000 Roman troops to destroy the Jewish community in Jerusalem.

The outcome?

The destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, which led to Jewish exile and the Jewish Diaspora, which led to socioeconomic and lethal antisemitism against Jews across the world, which led to pogroms, which led to modern Zionism, which led to the return to our indigenous homeland, which led to the creation of the State of Israel, which led to various Arab countries and factions using the Palestinians as a pawn to advance their own geopolitical agendas against Israel, which led to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, which brings us to where we are today.

You know, eight weeks after the worst attack against Jews since the Holocaust, after Palestinian terrorists infiltrated Israel, massacred more than 1,000 Jews, and took hostage well over 200 innocent people on October 7th.

How’s that for connecting the dots?

Throughout Jewish history, and especially in modern Jewish history, Jew-on-Jew hostilities have reared their ugly heads, and there are many reasons for it, such as:

Internalized antisemitism

Desire for assimilation

Perceived “white privilege”

Negative feelings regarding ethnocentrism

Lack of knowledge and education

Let’s take a look at each one:

Internalized Antisemitism

Internalized antisemitism is the concept that people can ingest and even accept stereotypes, discrimination, prejudices, and traumas experienced by a particular group of people, their ethnicity, or their religion.

Consider when hear about a Jewish person who commits some heinous crime, such as Bernie Madoff or Jeffrey Epstein. Rationally, there is no reason why the Jewishness of these criminals should make us feel ashamed by their actions, though I’ll bet that many of us Jews felt that shame.

And the main reason Jews feel it is because of the negative stereotypes that abound Jews, Judaism, and Jewish history. Jews are triggered by the nasty beliefs that others hold about us, which have become so entrenched in the soil of civilization, that many Jews have absorbed some of these beliefs ourselves.

Jewish shame has been a subject of fascination for many novelists. In Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question, the Finkler is an anti-Zionist Jew who is proud to be ashamed of the Jews’ nation state — so ashamed, he joins a group called “Ashamed Jews” and tweaks its typography to: ASHamed Jews. You know, the Jews whose gassed bodies were burned in the ovens of Auschwitz, they are (were) the good Jews. (People love dead Jews, as author Dora Horn wrote a book about.)

The ones who survived the systematic mass murder of Europe’s Jews and whose descendants now live in Israel, they are not. They are bad Jews who induce feelings of shame. When Finkler’s wife asks him to leave ASHamed Jews, Jacobson pokes delicious fun: “That far he couldn’t go. The movement needed him. The Palestinians needed him. The Groucho needed him.”

Hence why internalized oppression is likely to consist of self-hatred, self-concealment, fear of violence, and feelings of inferiority, resignation, isolation, powerlessness, and gratefulness for being allowed to survive.

Self-disgust, a construct which may be internalized from centuries of being treated as “contagion” and without the right of existence, is another way in which internalized antisemitism can manifest subtly. To this end, some Jews may perceive themselves as flawed. And, if they have tried their best to “shed” their Jewishness, reminders of it may stir up disdain, anxiety, and fear.

Of course, internalized antisemitism manifests along a continuum, with some aspects hidden to the eye, others visible if being looked for, and still other aspects displayed in rather appalling fashion. Some Jews have gotten rid of what are perceived as “traditional Jewish features” such as a strong nose, dark curly hair, or expressiveness of speech.

There are some Jewish men who never date Jewish women, which seems to be a clear indication of internalized oppression, but one which may not be recognized as such within the context of Jews. If one talks instead of a Black man who never dates Black women, the internalized aspect of hatred becomes more apparent.

Though internalized antisemitism can lead to Jewish self-hatred, the two phenomenon are different. Whereas internalized antisemitism is common in one form or another, actual self-hatred is probably rare. Most Jews who have seriously internalized antisemitism seem to be ambivalent about their Jewishness, rather than truly self-hating.

Desire for Assimilation

A logical response to looking at antisemitism is to wonder how Jews have coped, survived, and even thrived in the face of repeated persecution, forced conversions, and centuries of general oppression.

Many Jews, for example, responded to antisemitism in the 20th century by attempting to assimilate. They changed their names, altered their noses, modulated their tones, married non-Jews, didn’t teach their children the Jewish languages which they brought with them from the Old World, downplayed the communication styles which were perceived to be too loud and expressive, and at times incorporated Christian traditions into religious services to minimize their Jewishness.

Many other Jews shared the anti-oppression emphasis of the political left, and entered into leftist organizations. But here, too, they assimilate. These Jews believed they would be better off and less likely to be persecuted as Jews if they could show their non-Jewish neighbors that they were really just like them, that they really could behave in ways that were “inoffensive”(not different from the behavioral patterns of their non-Jewish neighbors), and that they really would not insist on specifically Jewish concerns within the left.

Another, and contradictory tactic, was to immerse oneself in traditional Jewish religious life, or Orthodoxy. While this was not just a response to antisemitism, antisemitism did influence the desire to have as little as possible to do with the painful world and ideas of the goyim (non-Jews).

Orthodox Jews were (and are) usually readily identifiable as Jews by the clothing they wear; they often live in tight-knit communities of other Orthodox Jews, and may view non-Jews (or even non-Orthodox Jews) as debased, and deeply untrustworthy.

The Zionist approach also attracted a number of Jews as resolution to the centuries-old yearning for the indigenous land from which Jews had been exiled. Underlying this desire, particularly in the post-World War II era, was the notion that creating and maintaining a viable Jewish state was the only real path to safety in a world which had mostly turned a blind eye to the repeated enactment of antisemitism.

Other Jews have tossed in their lot with the ruling classes. Though some of this may be ideological kinship, given the “rebellious spirit” of Judaism, and the inherent oppression built into ruling classes, this alliance may be more expedient than a partnership built solely on compatibility and true desire.

It is an old coping mechanism, however, for some Jews to align themselves with power in the hopes that when the temperature of antisemitism warms, these alliances will protect them.

Perceived ‘White Privilege’

Many people, both Jewish and not, who live in liberal democracies, proclaim that antisemitism has been eradicated in these places, and that Jews are now widely perceived to be “white people,” with the privileges that so-called white people enjoy.

The irony is that if Jews are white, with the assumption of power and privilege that “white people” hold, little-to-no room is left to examine either historical antisemitism or the ways in which antisemitism still plays out.

This cloak of whiteness prevents the exploration of Jews as 11 ethnic minorities with a unique history of oppression. At the same time, whiteness precludes Jews’ inclusion within a multicultural context where their equally unique and ongoing contributions to the world might be examined.

Without this examination, there is a shroud of ignorance and invisibility around antisemitism, and if non-Jews do not understand or recognize this phenomenon, not only is the possibility of it reoccurring great, but Jewish anxiety and vulnerability will be perpetuated.

Not to mention, Jews as a “white people” is intellectually dishonest. Currently, this claim ignores the some 60-percent of Jews in Israel who have Middle Eastern and North African descent, as well as all the Jews who have emigrated from the Middle East and North Africa to other countries not named Israel.

And, historically, this claim does not align with the Jewish story of an exodus from Egypt and subsequent settlement in the Land of Israel. Even though this story originated thousands of years ago, it’s suffice to say that the “original Jews” (the Hebrews, then the Israelites) were not white-skinned at all.

Negative Feelings Regarding Ethnocentrism

There are Jews who subscribe to Jewish exceptionalism, or, using biblical language, being “the Chosen People.” In the field of anthropology, this concept is known as ethnocentrism.

Within social justice movements, the phrase “internalized superiority” may at times be used to designate one way in which oppression impacts identity formation, in this case, thousands of years of persecution on Jewish identity. But if you (like me) are among the Jews who were educated with the worldview that all humans are created equal, you might be appalled by the concept of Jewish exceptionalism.

In general, many people who come into contact with concepts that contradict their worldviews have perverse reactions to such contradictions, since they can make you feel insecure (“Is it possible that I’ve been wrong all this time?”), vulnerable (“If what I’ve been taught is untrue, who am I and what do I stand for?”), and betrayed (“Could it be that my ‘teachers’ deceived me or led me down the wrong path?”)

These powerful and painful feelings of insecurity, vulnerability, and betrayal have a tendency to make people repel contradictory worldviews, because it’s far easier to repel them than it is to sit with these feelings and rework your worldviews. This is especially the case when a Jew’s non-Jewish worldviews are a significantly greater part of their personal identity and sense of self-worth than is their Jewishness.

Lack of Knowledge and Education

Many Jews believe the Holocaust happened in a vacuum, or that Jews have over-exaggerated their victimhood throughout history, including but not limited to Jews who have never really experienced antisemitism themselves.

This self-centered view produces a thought process like, “If I or those close to me have never directly experienced antisemitism, it must not be all that bad.” Yet it is this sort of mindset that’s ignorantly absent of Jewish history, which in turn could be a dangerous absence of knowledge and education (or effective education).

Many of these Jews do not know that Islamic cultures, while not as virulent in their expression of antisemitism as Christian ones, still proposed that Jews were second-class citizens who were taxed disproportionately and lived lives of precarious appeasement to whomever was in power.

Around the sixth century, in the expanding Arab world, Jews had to pay fees in exchange for safeguarding their life and property, as well as for the right to worship unmolested according to their conscience. Jews were also to conduct themselves with the demeanor and behaviors befitting a subject population.

They were never to strike a Muslim. They were not to carry arms, ride horses, or use normal riding saddles on their mounts. They were neither able to build new places of worship, nor repair old ones. They were not to hold public religious processions (including funeral processions) nor pray too loudly.

Most definitely, they were not to proselytize. They had to wear clothing that distinguished them from the Arabs. This insistence on social inferiority may be traced, at least in part, to the Jew’s rejection of both Jesus as Savior and Mohammed as Prophet, and to fears that Jewish ideas — Jewish “resistance” — would contaminate the loyal followers of Jesus and Mohammed.

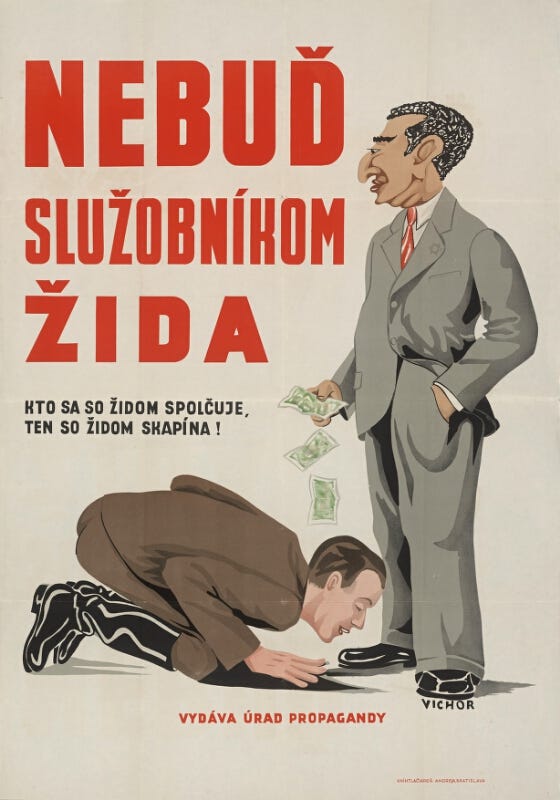

While these two religions ignited the initial flames of antisemitism and spread it throughout their growing empires, ruling classes have fueled the fire when it has been expedient for them.

This has worked in two main ways: One, Jews were forbidden in many places from owning land and from working in positions of skilled labor. They were, however, allowed to work with money, because money, moneylending, and money collecting were jobs full of risk and stigma, considered to be lowly and filthy.

Jews entered these ventures out of necessity because they were prevented from working in the guilds that were necessary to succeed in other trades, but their success in the moneylending and money-collecting fields, coupled with the illusion of “power over” poor peasants which these positions presented, became another reason for the masses to hate them.

It was at this time that Jews became the public face of the oppressor. The positions they occupied: tax collectors, foremen, innkeepers, and liquor distributors for the large landowners and feudal elite. To the ordinary serf or peasant, these Jews seemed to have immense power. It was to them that one had to pay the taxes or levies, to them that one paid for the goods that were being brought in from other areas, and to them that one had to appeal when facing arbitrary decisions of the landowners.

The stigma and hate attached to these positions landed on top of the suspicion and mistrust Jews already carried due to their historical convictions and status as outsiders.

It could be argued that antisemitism began to have a life of its own during Medieval Europe, capable of being spontaneously awakened simultaneous to social and economic unrest, a deeply and intricately imbedded construct in the (usually) non-Jewish psyche, mostly unconscious as a construct having to do with money, religion, and taboo is likely to be.

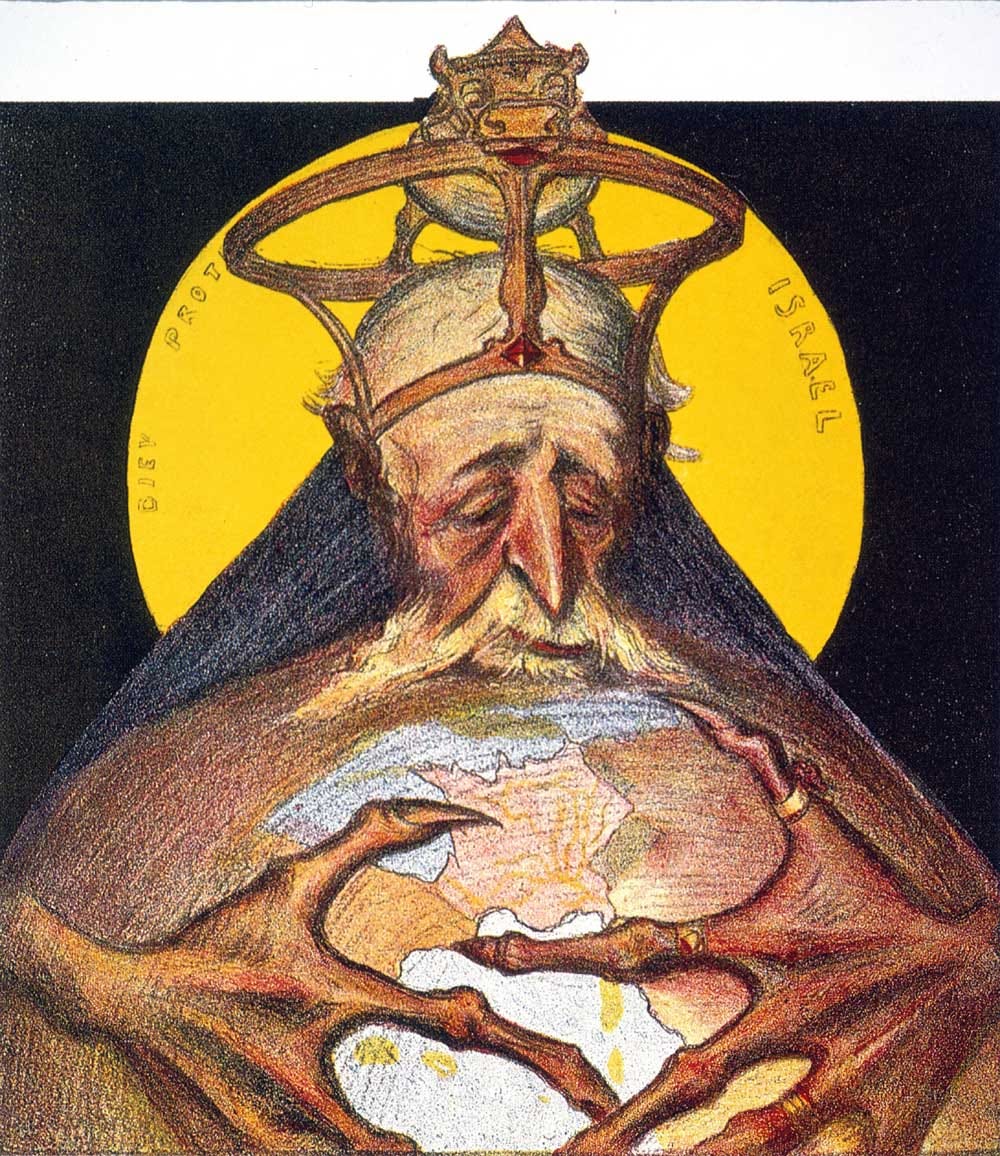

There are also history’s less-obvious forms of antisemitism, which includes the ideas that Jews control the media (if not the world); that they have more power than others (often with a sinister association); that they are without moral regard; that they are materialistic and difficult; that they cannot be trusted; that they are responsible for 9/11; and that Zionism equals racism, a charge justifying broad brush strokes of anti-Jewish sentiment.

A narrow focus on the human rights abuses of Israel while excluding the equally, if not more egregious, human rights abuses of its neighbors is also thought to be antisemitic and indicative of a double standard that may point the way to antisemitism in an era when oppression or hatred of any sort is more likely to be masked than in previous eras.

Some heavily liberal-minded Jews often comfort themselves by believing that they are personally far removed from the hatreds and discrimination of the past. We are aware of continued systemic racism and sexism, and, despite tremendous progress, know how much work there is still to do.

On the other hand, these heavily liberal-minded Jews may not realize how they are responsible for the perpetuation of common prejudices, as we all are, including Jewish liberals who are blind to their own antisemitism and their role in endangering Jews everywhere.

This is not a new problem on the left. Phyllis Chesler, author of the 2003 book The New Anti-Semitism, has been warning about antisemitism on the left and among feminists. For those professing to fight racism, prejudices, and bigotry, “antisemitism is the only acceptable form of racism,” according to Chesler.

This is belligerently revealed when the topic of Israel is raised among heavily liberal-minded folks, and especially when Israel dares to defend itself with military force. This observation is not meant to shut down dialogue and debate about Israel.

Rather, it is a call to be mindful of how internalized antisemitism plays a significant role in how we react to Israel’s actions, how we judge the Jewish state, and how we analyze the conflict between Israel, the Palestinians, and Arab states who use the Palestinians as a pawn to further their own geopolitical interests.

Further problematic is that we have been fed a steady diet of falsehoods about the creation of Israel, For instance, that the Jewish state was simply created because of the Holocaust. (It wasn’t.) That most or all Israelis are white colonizers. (Most of them aren’t white and most of them aren’t colonizers according to the very definitions of these terms.) And that Israelis stole land from the Palestinians. (They didn’t.)

What’s more, many liberals have no deep knowledge of history, instead hiding behind an anti-Zionism agenda that has intellectualized and rationalized antisemitism by dressing up centuries-old Jew hate in modern-day academia.

Perhaps because we hoped antisemitism would end after the unthinkable tragedies of the Holocaust, and some assumed it did. One only has to look at the demonstrations and behaviors on the streets of London, Paris, Washington, D.C., New York City, and Berlin, and the defamation on social media, as well as the hate from the mouths of elected officials, to notice that this assumption is so evidently wrong.

Antisemitism encourages unhinged rage against Israel and Israelis, a level of rage expressed against no other country and no other people. It permits the viewing of Israel as uniquely racist, oppressive, and evil — instead of being seen as ordinary or all too human. Even what people call “soft” or “positive” antisemitism encourages double standards and unfairly heightened expectations for Israel, which faces extraordinary challenges from enemies sadly lacking respect, dignity, and morality.

Antisemitism also makes it easy for people to believe numerous Blood Libels about Israel, such as the charge that it is committing genocide or engaging in ethnic cleansing. This is no different than when people actually believed that Jews murdered God in the form of Jesus, drank the blood of Christian children, and caused the bubonic plague.

Anti-Zionist movements have made this further acceptable by attempting to intellectually separate Jews outside of Israel from those within Israel, in effect saying it’s okay to hate these Jews over here or Jews who support them (i.e. Zionists). At a minimum, to repeat such modern Blood Libels as gospel truth is to recklessly support those calling for the genocide of the Jews, for who is more worthy of killing than people who are “guilty” of committing genocide?

Empathizing with civilians in Gaza, promoting the creation of a Palestinian state, criticizing Israel’s settlement policy, its mistakes in war and peace, and its flaws as a society is not antisemitic.

But if you do the foregoing without learning about the history and context of Israel’s actions and those of its enemies; if you only question the right of the Jewish People to self-determination or endlessly seek to re-litigate the creation of the modern State of Israel; if you support an economic, academic, or other boycott of Israel but not of other countries you believe are violating human rights; if you seek moral equivalence between Israel and Hamas (a terrorist group whose stated purpose is the destruction of Israel and all Jews); if you presume Israel guilty of war crimes before investigations are made; if you believe Israel is uniquely evil or the root of all problems in the Middle East; if you believe in Israel’s self-defense theoretically but not in actuality; if you view this current war in Gaza as different from all other wars and the civilian casualties as different from other civilian casualties in war, you must ask yourself why.

Martin Luther King, Jr. would tell you there’s a word for this. It’s called antisemitism.

There’s an even more disturbing trend: Some Jews are finding it difficult to recognize veiled antisemitism. Often this antisemitism comes from people they know fairly well. When confronted with the reality that friends and coworkers were never really friendly, it’s easier to dismiss the evidence than deal with the reality of the situation. In my experience, gentiles may recognize this form of antisemitism before Jews do.

I thank you for breaking your thesis down into the categories cited, and your detailed explanation of each. I would not call those who have intellectualized the issue of antisemitism as having a high intellect. Those who do, would seek out multiple sources of information, be well read, and knowledgeable, and above all, ask questions. Also, this same group seems to use emotion to cloud any cogent thinking. There are many Noam Chomsky's in the world, and no matter what you say in defense of Israel, will listen but not want to really know any of it. Self hating Jews have always tried to make themselves into what they thought the outside world wanted them to be. They should realize no matter what they do, they will still be looked upon as Jews (of course, a very good thing). Just as in Poland and Germany, when Jews thought their 'neighbors, shopkeepers" were good friends, they found out how fast they were given up to the Nazis.