You've never heard a Palestinian say this before.

"I think that even if there was a Palestinian state, it would fail. It wouldn't work. We Palestinians wouldn't know how to run it."

Please consider supporting our mission to help everyone better understand and become smarter about the Jewish world. A gift of any amount helps keep our platform free of advertising and accessible to all.

This is a guest essay written by Joel Meyer, an educator and speaker who writes the newsletter, “Simply Complicated.”

You can also listen to the podcast version of this essay on Apple Podcasts, YouTube Music, YouTube, and Spotify.

A few years ago, I was touring Jerusalem’s Old City with a group of American senior citizens.

It was mid-afternoon, and I could see that some members of the group were tired and would appreciate finding a place to sit down and rest.

I led them into Souk al-Qattanin, a 14th-century cotton traders’ market built by the Mamluks, who had expelled the Crusaders from the Holy Land several centuries earlier. Today, few cotton traders remain in the small shops, which now mostly sell shawls, headscarves, items used for Islamic rituals and prayer, and brightly colored candies.

The wide but dimly lit market street is still an impressive sight, and the excitement of entering it is heightened by the opportunity, at its far end, to gaze up a set of steps and through an imposing gateway onto the Al-Aqsa complex — the Temple Mount — and catch a glimpse of the Dome of the Rock’s gold-plated roof.

My travelers excitedly took photographs as local Palestinian Muslims ascended and descended the steps, entering and exiting the holy compound.

As non-Muslims, this was as close as my travelers could get.

Instead, I took them a few steps back along the market street to sit and drink coffee at Abu Musa’s coffee shop.

Abu Musa’s coffee shop, thankfully, looks nothing like a typical Starbucks. His freshly brewed Arabic coffee and mint tea are prepared inside a cramped niche just off the street. Those who come to drink sit on small stools on either side of the cobbled street as locals walk by.

A short distance from where Abu Musa prepares the coffee is a gateway leading to an indoor space large enough for 15 to 20 people to sit. This area serves as a place of Islamic prayer for local shopkeepers during the day but, when unoccupied, provides an excellent spot for a small group of tourists to rest and watch the world unfold around them.

I had first met the group about three weeks earlier. Their trip had begun with three days in the West Bank, guided by a Palestinian, followed by a few days touring Tel Aviv and Jaffa with me before continuing on to Haifa and the Golan Heights. After bidding me farewell, they traveled to Egypt, exploring the land of the Pharaohs with an Egyptian guide, before heading to Jordan, where they were accompanied by a Jordanian guide — himself a Palestinian.

The group had now returned to me for the final two days of their trip, in order to explore Jerusalem. They returned to me, not only after many memorable experiences, but also with some very strong and confidently held views on the region and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

I helped Abu Musa bring the coffee and tea I had ordered for the group and then sat down to speak with them. Earlier, we had examined the Jewish connection to Jerusalem, and later we would walk the Via Dolorosa and visit the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Now was the time to discuss the Islamic theological connection to Jerusalem — Al-Quds — as well as the Muslim-Arab conquest of the city in 637 CE, led by Caliph Omar Ibn Al-Khattab.

However, just before we began our discussion, I saw a friend passing by, descending the steps after praying at Al-Aqsa. We caught each other’s gaze, and he came over to greet me.

Ahmed (I have changed his name to respect his privacy) and I met nearly eight years ago — actually over coffee at Abu Musa’s. He has helped me many times when I have guided Muslim travelers.

The Islamic Waqf, responsible for administering the Al-Aqsa complex (the Temple Mount) allows only Muslims to pray at the site. Aside from certain times, only Muslims are permitted to enter the site at all.

Even when non-Muslims are permitted to enter, the Islamic Waqf does not allow them to enter the holy buildings, such as the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Waqf’s decision to restrict access to non-Muslims is not based on Islamic religious law but rather on political considerations.

When I have guided Muslim travelers but was not allowed to join them at Al-Aqsa, Ahmed has kindly accompanied them, helping them navigate the Mount, visit the holy sites, and even taking pictures of them at prayer before safely returning them to me.

After exchanging a hug and some pleasantries, I asked Ahmed if I could bring him a cup of coffee and whether he would be willing to speak with the group. He readily agreed and asked me what I wanted him to say. I replied that he should speak freely about anything he wished and that the group was particularly interested in the conflict and how, if at all, it could be resolved.

In a moment, I’ll tell you about Ahmed’s conversation with the group, but first, I’ll provide some geopolitical and historical context to help you better understand the reality of Jerusalem and its Arab and Jewish residents.

Jerusalem was conquered by the Ottomans and incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in the early 16th century. In 1917 and 1918, the area known as “Palestine” (which then encompassed modern-day Gaza, Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan) came under British control.

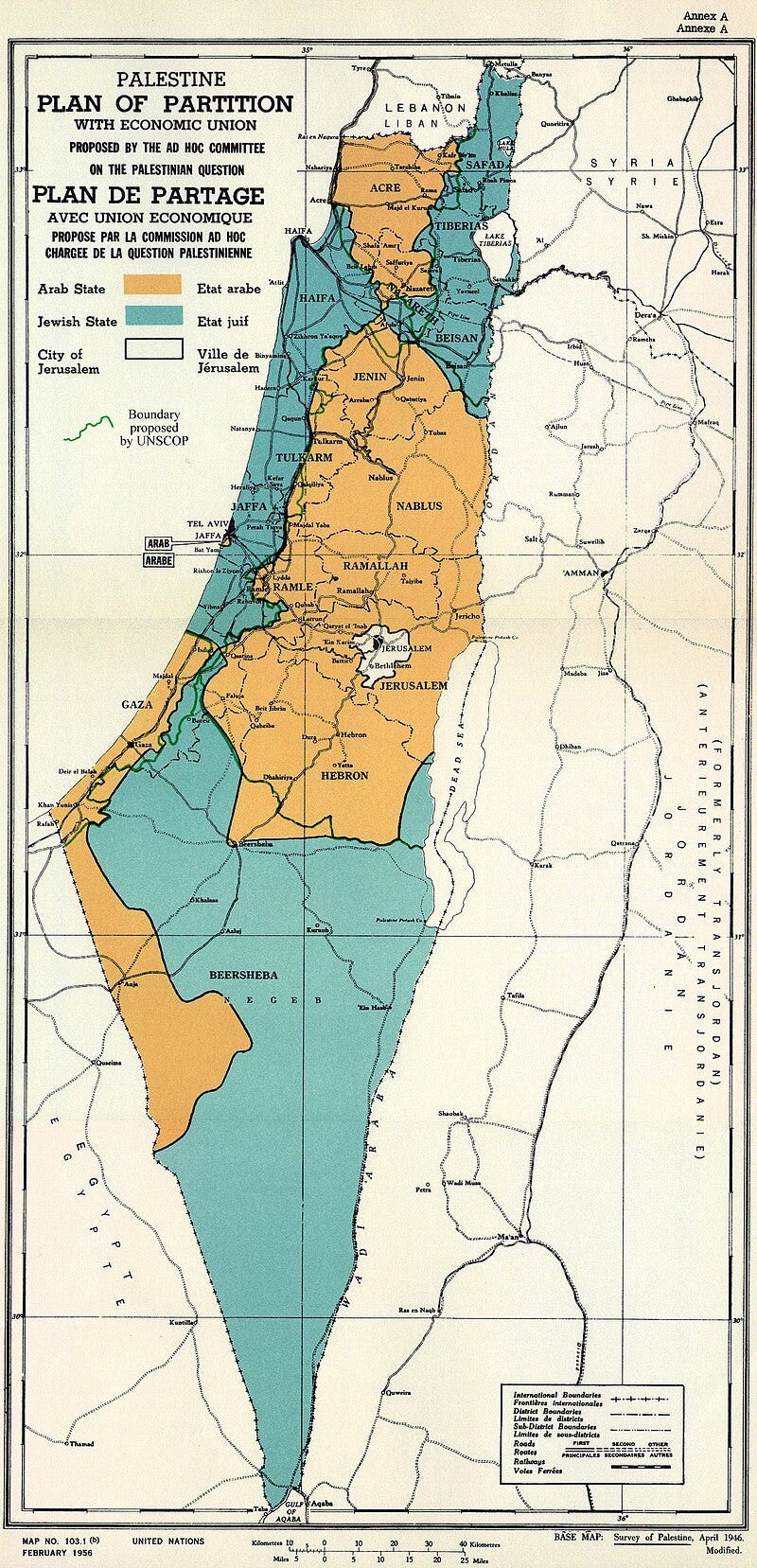

Following World War II and the British decision to relinquish control of Mandatory Palestine, the United Nations Partition Plan of November 1947 designated that the remaining part of Mandate Palestine (which had not already become the independent Hashemite-Arab Kingdom of Jordan) would be divided into two states, one Arab and one Jewish. Jerusalem was not to be part of either state; instead, it was to become an international city.

The Jewish leadership in Palestine accepted the plan, but the Palestinian Arab leadership rejected it and took up arms against the Jews. As a result, the plan was never implemented, and a civil war between Jews and Arabs broke out in late 1947.

In May 1948, as the British were completing their withdrawal from Palestine, the Jewish leadership declared the establishment of a state. Immediately, the surrounding Arab countries attacked, supporting Palestinian Arab forces that had already been fighting with the Jews since late 1947.

Following the declaration of the state, the Jewish Quarter of the Old City, already besieged by the Jordanian Arab Legion, came under further heavy military pressure. Just two weeks after the establishment of the modern State of Israel, the Jewish Quarter and the entire Old City of Jerusalem fell to the Jordanians. Jews living in the Old City were either taken as prisoners of war by the Jordanians or forced to leave.

By the end of 1948, Jerusalem was clearly divided into two parts — East and West. East Jerusalem came under Jordanian control, while West Jerusalem was under Israeli control. All Jews living in East Jerusalem were displaced, moving to Jewish-controlled areas, and the majority of Arabs living in West Jerusalem relocated to areas under Jordanian control.

“East” and “West” are as much political terms as they are geographical ones. The dividing line, known as the Green Line, was an arbitrary and temporary ceasefire boundary drawn by Israeli and Jordanian commanders in the field. It was never recognized as a permanent border by either side, yet for 19 years, it functioned as a de facto border between Israel and Jordan.

Israel declared Jerusalem its capital, though it controlled only the western part of the city. This decision, enshrined in Israeli law, remains a source of international controversy to this day.

Along with the West Bank, Jordan annexed East Jerusalem, including the entirety of the Old City, declaring it part of Jordan and applying Jordanian law to the area and its Palestinian Arab residents. Despite this annexation being illegal under international law, Jordan’s occupation and subsequent annexation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank — a move recognized only by the governments of Great Britain and Pakistan — are rarely discussed and are not widely considered controversial.

Following the signing of the armistice agreement between Israel and Jordan in 1949, residents of Israeli-controlled West Jerusalem — predominantly Jewish but also some Arabs — became Israeli citizens. Meanwhile, the majority of residents in Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem, now exclusively Arab, were granted conditional Jordanian citizenship.

However, new Palestinian Arab residents of East Jerusalem who had fled or been displaced from areas that became Israel during the war did not receive Jordanian citizenship. Instead, they were placed in refugee camps established by the newly created United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which was tasked with caring for Arab refugees displaced from what had become the State of Israel.

The same situation applied to Palestinian Arabs throughout the West Bank. Those who had lived in the West Bank before 1948 received conditional Jordanian citizenship, while those arriving from areas that had become part of Israel were placed in UNRWA administered refugee camps and were denied Jordanian citizenship, despite Jordan’s annexation of the territory.

In 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organization was formed at the Arab summit in Cairo. At that time, Gaza was under Egyptian occupation, and Jerusalem and the West Bank were under Jordanian control. The Palestine Liberation Organization was not created to resist Egyptian or Jordanian occupation (in fact Egyptian and Jordanian representatives were present in the room at the time of the organization’s establishment) but rather with the stated goal of dismantling the State of Israel.

During the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel captured East Jerusalem and the West Bank from Jordan. While the West Bank came under Israeli military occupation, East Jerusalem, including the Old City, was related to differently. In Israeli political discourse, East and West Jerusalem were “unified,” and a Basic Law officially annexing East Jerusalem to Israel was officially passed by the Knesset — Israel’s parliament — in 1980.

Palestinian Arabs living in Gaza and the West Bank are neither Israeli citizens nor considered residents of Israel under Israeli law. However, Palestinian Arabs in East Jerusalem are considered residents of Israel.

East Jerusalem Palestinian Arabs were not forced to adopt Israeli citizenship (international law prohibits the compulsory imposition of citizenship on an occupied population), but they were granted permanent residency in Jerusalem, which is part of Israel under Israeli law. They may apply for Israeli citizenship, and as of today, approximately five percent of the 380,000 Palestinian Arabs living in East Jerusalem have become Israeli citizens.

As non-citizens, permanent residents of Jerusalem cannot vote in Israeli national elections, but they are eligible to vote in municipal elections. However, in practice, few East Jerusalem Palestinian Arabs exercise their right to vote in local elections. Within Palestinian society, participation in these elections is seen as a form of normalization with what is widely viewed as an “illegal occupying power.”

Those who intend to vote or run for office are often threatened. This lack of electoral participation contributes to the lack of political accountability toward East Jerusalem’s Arab residents and does little to address the social and economic inequalities between different parts of the city and different segments of the population.

Returning to Abu Musa’s coffee shop, Ahmed came to sit with the group. After introducing him, I moved to the side, giving Ahmed the stage and indicating to the group that I had no intention of steering the conversation or filtering questions and answers.

Ahmed began by sharing a little about his family, who have lived in Jerusalem for multiple generations. He explained that he was born in the Old City in 1965, then part of Jordan, and that he holds Jordanian citizenship. The group asked Ahmed about life in Jerusalem under Israeli control, the changes he had witnessed, and his views on Israel’s government.

I had never previously engaged in a deep and meaningful discussion with Ahmed about our respective views. Like the group, I found much of what he said enlightening, even if I did not fully agree with all his perspectives.

Then, as our time together was coming to an end, one of the travelers shifted the discussion to the question of how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict might be resolved. Ahmed’s response surprised many in the group, as it contradicted much of what they had presumed to be true. Here is the exchange:

Traveler 1: Why is there no peace between Israel and Palestine?

Ahmed: The answer is the politicians.

Traveler 2: But what about Mahmoud Abbas (the President of the Palestinian Authority)?

Ahmed: Yes. He is a politician too.

Traveler 2: So you mean politicians on both sides are the problem?

Ahmed: Yes, of course. Netanyahu is a problem. The Israeli government doesn’t want a solution, and the illegal Israeli occupation must end. But our Palestinian politicians are a problem too. Abbas is corrupt, steals from the people, and doesn’t want to help. Our politicians benefit and get rich from the conflict.

Traveler 1: So do you think a two-state solution (Israel and Palestine) is the answer?

Ahmed: No. I think that even if there was a Palestinian state, it would fail. It wouldn’t work. We Palestinians wouldn’t know how to run it.

Traveler 3: So if you don’t think a Palestinian state is the solution, what is? What do you think should happen?

Ahmed: I was born in 1965. At that time, there was no Palestinian state. This place was Jordan. Before Israel occupied Jerusalem and the West Bank in 1967, we did not talk about a Palestinian state. We did not talk about Jordan leaving. This was Jordan, and I am Jordanian. My solution would be for Israel’s occupation here to end and for Jordan to return to rule over the West Bank and Jerusalem.

Ahmed finished speaking, and several members of the group rose to shake his hand. As he was about to leave, he took me aside to ask whether what he had said was acceptable. I assured him that it was and reiterated that it is so important to me that my travelers hear different perspectives — not just mine or those of people who share my views.

To be honest, although I had long known that Ahmed was deeply critical of Israel, we had never discussed possible solutions to the conflict. His response on this question surprised me, as did his willingness to share it with the group.

We continued our tour, walking the Via Dolorosa and visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, but later, as we sat down to reflect on the day, our meeting with Ahmed naturally became a major topic of discussion.

Some members of the group had arrived for the trip with little historical or contextual knowledge or deep understanding of the complex geopolitics of the region. Others had come with strong preconceived notions — specifically, that Israeli intransigence was largely responsible for the failure to reach a political resolution of the conflict, and that Palestinians had little agency or responsibility for the situation.

I came to understand that these views had been further reinforced by conversations the group had with guides in the West Bank and Jordan. The Palestinian guide had declined to speak about the challenges of Palestinian self-governance or internal issues within Palestinian society. For the Jordanian guide — himself a Palestinian, like many of his countrymen — the inalienable starting point for political discussions with the group had been the assertion that Israel was an “illegitimate settler-colonial state.”

These approaches differ from my own. Those familiar with me know that I strive to be fair and balanced, to present multiple narratives, and to clearly differentiate between my own opinions and what can be considered objective facts.

Ahmed’s perspective not only presented many in the group with an alternative view of the conflict, but also led some to reconsider whether the dominant narratives they had encountered — whether in the media or among academic circles — were fully grounded in objective truth or whether certain elements of reality were being filtered out, perhaps deliberately.

Ahmed is a Palestinian Arab. He considers Israeli control of East Jerusalem, the Old City, and the West Bank illegitimate. He believes Israel was born in sin and that the war of 1947 to 1949 was the “Nakba” — a catastrophe inflicted upon the Arab population of Palestine by the Jews.

And yet, Ahmed expressed a view rarely stated openly by Palestinian Arabs, one more commonly associated with the Israeli Right than with those who define themselves as “pro-Palestinian” — that, unlike the Jews of British Mandate Palestine, the Palestinian Arabs had not sought an independent Palestinian Arab state. Ahmed had clearly articulated the argument that prior to 1967, the Arabs of East Jerusalem and the West Bank had not sought an end to Jordanian rule over them, even as they aspired to dismantle the Jewish state to their west.

On one hand, Ahmed’s description of Israel’s birth as illegitimate placed him ideologically in the same camp as Israel’s most vociferous opponents. On the other hand, his belief that an independent Palestinian state is neither necessary nor advisable — having intimated at a lack of significant social, national, or religious differences between Palestinian Arabs and Jordanians — aligns with some of the more extreme pro-Israel positions, which assert that there is no such thing as a distinct Palestinian national identity.

Please understand: I do not share this story to persuade you to adopt Ahmed’s perspective or any other. I know Arab citizens of Israel who define themselves as Palestinians and advocate for a peaceful bi-national state of Arabs and Jews. I know Israeli Jews who believe that Israel should annex the West Bank and eliminate the possibility of a future Palestinian state.

I know East Jerusalem Palestinian Arabs who would prefer to remain under Israeli sovereignty, even if a Palestinian state was established in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. I know both Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs who believe that some form of a two-state solution is ultimately the only way to ensure security and national rights for both peoples.

I also know Palestinians who believe that the goal of destroying Israel should never be abandoned. I know people who blame Israel for everything. I know people who blame the Palestinians for everything.

Dialogue and progress are only possible when we are prepared to listen to a multitude of perspectives; especially those that we disagree with, or which make us feel uncomfortable.

I do not share this story to convince you to adopt any particular narrative. My goal is to highlight that people’s identities are complex and that reality is indeed complicated.

Failing to acknowledge and embrace this complexity — opting instead for an oversimplified understanding of the world — is dangerous.

As I write this, hundreds — if not thousands — of Gazans have been bravely demonstrating against Hamas in the Strip. Yet few of those around the world who have marched in “pro-Palestinian” and “anti-Israel” demonstrations over the past year and a half stand in solidarity with them. Few write supportive comments online, and few question why their favorite Gazan vlogger has continued to speak against Israel, while failing to acknowledge the existence of any protests by ordinary Gazans against Hamas’ rule.

I have little doubt that most of those risking their lives in Gaza to protest against Hamas also harbor deep anger toward Israel. And yet, those who claim to stand for Palestinians are not amplifying these Palestinian voices on campuses or in the streets.

Why not?

Because in a world where everything is framed as a zero-sum game — where Hamas opposes Israel — amplifying the voices of Palestinians who oppose Hamas must, in some way, be tantamount to supporting Israel.

In a world where identities are viewed as one-dimensional, and complexity is pushed aside in favor of banal slogans and oversimplified narratives, such a macabre and absurd paradigm appears to make sense. And the biggest losers are those Palestinians who seek a different reality.

It should be noted that this disease of binary thinking — the insistence on oversimplifying complex issues — is far from limited to the subject of “Palestine.”

You can be certain that the overwhelming majority of those Israelis who are, at this very moment, protesting against their own government and demanding that hostage negotiations be prioritized over military objectives, also oppose Hamas and want to see it removed from power.

Yet the Israeli Far-Right views these protesters as unpatriotic traitors, while many of the global “anti-Israel” Far-Left cite the protests as further proof of Israel’s illegitimacy.

Neither position is true, and both are dangerous, fanning the flames of intransigence and extremism.

Imagine how different things could be if the loudest voices were instead those willing to acknowledge that reality is complex and nuanced — and that people are complicated.

What a fascinating and revealing piece! I do tend to agree with Ahmed when he says Palestinians would not be able to run their Country. They have one objective and would cut off their nose to spite their face!

Ahmed’s assertion that Jordon should be the rightful government for the West Bank (again) is a very interesting take. His assertion that the Palestinians themselves do not have the ability or inclination to govern themselves is enlightening and we have witnessed this for the last 50 years. However, let’s not forget that the Palestinians rose up against the Jordanian government in September, 1970 to overtake their Hashemite government/kingdom. This flies in the face of those Palestinians who think that they would be satisfied with their own country.

Arafat had several opportunities to gain Palestinian statehood. Each time after acceptance, he went back on his word. He would have rather continue having his people in “victimhood” and “resistance” than to accept the fact that Israel is permanent.

Further, as an experiment in self government, Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005 (under protest by the settlers) as an “experiment” in self government and self determination. We have seen the results of that failed experiment come to fruition 10/7.

10/7 pretty much killed any idea of a “2 state solution”.

We now need to think “outside the box” and, love it or hate him, DJT shifted the paradigm with his “outlandish” proposal of ridding Gaza of Gazans and starting over.